Deriving a Closed-Form Solution of the Fibonacci Sequence

The Fibonacci sequence might be one of the most famous sequences in the field of mathematics and computer science. High school students starting with programming classes already compute the first few Fibonacci numbers with their programs using different iterative or recursive approaches. One reason for its popularity might be that the Fibonacci sequence is closely related to many other fields of math and physics, often in astonishing ways that one might not expect. Usually, the Fibonacci sequence is defined recursively. Hence, to compute the n-th Fibonacci number, all previous Fibonacci numbers must be calculated first. In this blog post, we will derive an intriguing closed-form solution to directly compute any arbitrary Fibonacci number without first obtaining its predecessors. Interestingly, we will solve this problem with the help of a tool – the so called Z-Transform – which is actually more common in the field of digital signal processing.

The Fibonacci sequence, starting with

\[F_0 = 0, \, F_1=1\]can be defined recursively as

\[\begin{align} F_n = F_{n-1} + F_{n-2}, \, \, \mbox{for} \, n \in \mathbb{N}_{>1}. \label{eq:fibo} \end{align}\]A simple recursive function in R, implementing the sequence could look like this:

fibo <- function(n) {

if(n<0) return (NaN);

if(n == 0 ) return (0);

if(n == 1) return (1);

return (fibo(n-1) + fibo(n-2));

}

sapply(0:19, fibo)

The first 20 elements \(F_0 \ldots F_{19}\) of the Fibonacci Sequence are thus:

\[\begin{align} 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, 987, 1597, 2584, 4181. \end{align}\]Surprisingly (maybe not really, if you think about it), the Fibonacci sequence can also be generated using an IIR (infinite impulse response) filter. Consider the difference equation of an IIR-filter in the form:

\[\begin{align} y[n]=y[n-1]+y[n-2]+x[n-1]. \end{align}\]The impuls response of this filter is defined as:

\[\begin{align} h[n]=h[n-1]+h[n-2]+\delta[n-1], \end{align}\]where \(\delta[n]\) is the Kronecker Delta-Function. So at the time \(n=1\), we give a single impulse into our system and it starts running and computing a sequence of numbers. We get:

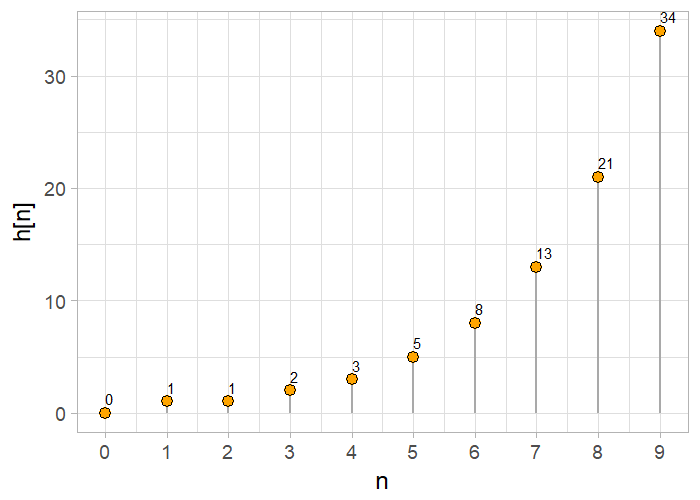

\[\begin{align} h[0]=0 \\ h[1]=1 \\ h[2]=1\\ h[3]=2\\ \vdots \end{align}\]Now, let us compute the impulse response for the given filter with some code and plot the results. Since the filter coefficients usually have to be passed differently to most functions of the DSP toolboxes, which requires reading off the coefficients from the transfer function \(H(z)\), let us first compute the transfer function (the Z-transform of our filter in the time domain):

\[\begin{align} y[n]=y[n-1]+y[n-2]+x[n-1] \\ \mathcal{Z} \{ y[n] \} = \mathcal{Z} \{ y[n-1] \} + \mathcal{Z} \{ y[n-2] \} + \mathcal{Z} \{ x[n-1] \}\\ Y(z) = z^{-2}Y(z) + z^{-1}Y(z) + z^{-1}X(z) \\ Y(z) - z^{-1}Y(z) - z^{-2}Y(z) = z^{-1}X(z) \\ Y(z) \big(1- z^{-1} - z^{-2} \big) = z^{-1}X(z)\\ H(z)=\frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} = \frac{z^{-1}}{1- z^{-1} - z^{-2}} \label{eq:z-transform} \end{align}\]Now, we can read off the filter coefficients (from the numerator for the forward coefficients and the denominator for the reverse coefficients). Hence, the forward coefficients are

\[\begin{align} b = [0, 1] \end{align}\]and the reverse coefficients are

\[\begin{align} a = [1,-1,-1]. \end{align}\]Subsequently, we can compute and plot the impulse response of our system.

library(signal)

library(ggplot2)

b = c(1)

a = c(1,-1,-1)

h <- impz(filt=b,a=a, n=10)$x # compute impulse response for our Filter

# Plot the impulse response

df <- data.frame(x=h$t, y=h$x)

p <- ggplot(data = df, aes(x=x, y=y)) +

geom_segment( aes(x=x, xend=x, y=0, yend=y), color="darkgrey", size=1) +

geom_point(size=4, shape=21, fill="orange") +

geom_text(aes(label=y),hjust=0, vjust=-.7) +

theme_light(base_size = 18)+

scale_x_continuous(breaks=c(0:10))+

xlab("n")+

ylab("h[n]")

p

The impulse response corresponds precisely to the Fibonacci sequence.

In Eq. \eqref{eq:z-transform}, we already computed the transfer function of our “Fibonacci”-filter. Let us see if we can obtain another representation of the impulse response in the time domain, which is no longer recursive and depicts a closed-form description of the Fibonacci numbers. Such a representation would be astonishing. We will do the following:

- Compute the partial fraction decomposition of our transfer function in Eq. \eqref{eq:z-transform}

- Look at the Z-transform of a certain type of infinite series

- Use the insights from 2. to transform our transfer function back into the time domain and remove the recursive structure of the impulse response

- Take the new impulse response to generate arbitrary Fibonacci numbers immediately

1. Partial Fraction Decomposition of H(z)

Initially, we have to find the poles of our system

\[\begin{align} H(z)=\frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} = \frac{z^{-1}}{1- z^{-1} - z^{-2}}, \end{align}\]hence, the roots in the denominator:

\[\begin{align} z^2-z-1=0. \end{align}\]The 2 (non-complex) roots can be trivially found to be:

\[\begin{align} z_{1,2}=\frac{1}{2}(1\pm \sqrt 5). \end{align}\]Now we can write our transfer function as:

\[\begin{align} H(z)=\frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} &= \frac{z^{-1}}{1- z^{-1} - z^{-2}} \\ &= \frac{z^{-1}}{\big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1} \big) \big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}\big)} \\ &= \frac{A}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} + \frac{B}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} \end{align}\]To find the constants \(A\) and \(B\), we can multiply with the denominator of each term and evaluate the expression at the poles we found previously (done exemplarily here for the constant \(A\)):

\[\begin{align} z^{-1}\frac{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1}}{\big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1} \big) \big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}\big)} = A + \frac{B \big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1}\big)}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} \\ \frac{z^{-1}}{\big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}\big)}\Bigg|_{z = \frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)} = A + \frac{B \big(1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1}\big)}{\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}}\bigg|_{z = 1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)} \\ \end{align}\]Since the term with the constant \(B\) vanishes due to the vanishing numerator, this leads to

\[\begin{align} A &= \frac{z^{-1}}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}}\Bigg|_{z = \frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)} \\ &= \frac{2(1 +\sqrt 5)^{-1}}{1- \frac{\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)}{\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)}} \\ &= \frac{2(1 +\sqrt 5)^{-1}}{\frac{1 +\sqrt 5 - (1 -\sqrt 5)}{1 +\sqrt 5}} \\ &= \frac{2(1 +\sqrt 5)^{-1}(1 +\sqrt 5)}{2\sqrt 5} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt 5}. \\ \end{align}\]Similarly, we obtain the constant \(B\):

\[\begin{align} B = -A = -\frac{1}{\sqrt 5}. \end{align}\]This let’s us finally write our previous transfer function as:

\[\begin{align} H(z)=\frac{Y(z)}{X(z)} &= \frac{1}{1- z^{-1} - z^{-2}} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt 5}\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} - \frac{1}{\sqrt 5}\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} \label{eq:partialfrac} \end{align}\]2. Determing the inverse Z-Transform of a special Transfer Function

To transfer our transfer function in Eq. \eqref{eq:partialfrac} back into the time domain, we have to find a suitable inverse transformation for an expression of the type

\[\begin{align} X(z) = \frac{b}{1-az^{-1}}. \label{eq:ztransinfinite} \end{align}\]This is not a trivial task. However, if we remember the geometric series, we might be able to continue. We notice that the infinite sum

\[b\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} q^k\]converges to

\[\begin{align} b\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} q^k = \frac{b}{1-q}, \label{eq:geom} \end{align}\]if \(|q|<1\).

If we look at Eq. \eqref{eq:ztransinfinite}, we can see that we have something which is very similar to Eq. \eqref{eq:geom}. By identifying

\[q = az^{-1}\]we can write

\[\begin{align} X(z) &= \frac{b}{1-az^{-1}} = b\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (az^{-1})^n \\ &= b\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a^nz^{-n} \label{eq:sumZ} \\ &= b(1 + az^{-1} + a^2 z^{-2} + \ldots) \end{align}\]Note that this step assumes that \(|az^{-1}|<1\) or \(|a|<|z|\) .

For this sum that we found, the inverse Z-transform can now be easily determined:

\[\begin{align} x[n] &= \mathcal{Z}^{-1}\big\{X(z)\big\}\\ &= b a^n u[n], \\ \end{align}\]where \(u[n]\) is the unit-step function which turns on at \(n=0.\) This is necessary, since the sum in Eq. \eqref{eq:sumZ} starts with \(n=0\) and \(x[n]\) is not defined (or is zero) for negative indexes.

We can summarize the findings of this section in basically one equation:

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{Z}\big\{b a^n u[n])\big\} &= \frac{b}{1-az^{-1}}. \label{eq:finalrelation} \end{align}\]3. Inverse Transform of the previous Partial Fraction Decomposition

We are ready to transform Eq. \eqref{eq:partialfrac} back into the time domain by using the relation in Eq. \eqref{eq:finalrelation}. Let’s do it. Remember:

\(\begin{align} H(z)=\frac{1}{\sqrt 5}\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} - \frac{1}{\sqrt 5}\frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)z^{-1}} \end{align}\)

This leads us to:

\[\begin{align} h[n] &= \mathcal{Z}^{-1}\big\{H(z)\big\} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \Big[\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)\Big]^{n}u[n] - \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \Big[\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)\Big]^{n}u[n] \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \Big[\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)\Big]^{n} - \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \Big[\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)\Big]^{n}, \, \mbox{for} \, n \ge 0 \label{eq:backintime} \end{align}\]which – when looked at closer – is a truly remarkable result. There is no longer a recursive formulation in the impulse response. This means we can directly compute any arbitrary Fibonacci number using this closed-form solution.

Another interesting observation from the above equation is that the term \(\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)\) is the so called golden ratio \(\varphi.\) The golden ratio has many exciting properties that one should look at. In this case, we will use it to simplify our expression above.

Using \(\varphi = \frac{1 +\sqrt 5}{2}\) and the additional relation

\[\begin{align} -\frac{1}{\varphi} &= -\varphi^{-1} = -\frac{2}{1 +\sqrt 5} \\ &= -\frac{2}{1 +\sqrt 5} \frac{1 -\sqrt 5}{1 -\sqrt 5} \\ &= -2 \frac{1 -\sqrt 5}{(1 +\sqrt 5)(1 -\sqrt 5)} \\ &= -2 \frac{1 -\sqrt 5}{1 - 5} \\ &= -2 \frac{1 -\sqrt 5}{-4} \\ &= \frac{1 -\sqrt 5}{2} , \end{align}\]we can re-write Eq. \eqref{eq:backintime} in the following way:

\[\begin{align} h[n] &= \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \Big[\frac{1}{2}(1 +\sqrt 5)\Big]^{n} - \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \Big[\frac{1}{2}(1 -\sqrt 5)\Big]^{n} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} \varphi^{n} - \frac{1}{\sqrt 5} (-\varphi)^{-n} \\ &= \frac{\varphi^{n} - (-\varphi)^{-n}}{\sqrt 5}\\ &= \frac{\varphi^{n} - (-\varphi)^{-n}}{2\varphi -1}, \end{align}\]which is – as I find – a really stunning formulation of the Fibonacci sequence. (There are also some issues with the above representation, but let’s forget about them at the moment.)

4. Compute arbitrary Fibonacci Numbers using the Closed-Form Solution

A simple R-function implementing this closed form solution could look like this:

fibo <- function(n) {

phi = (1+sqrt(5))/2

(phi^(n) - (-phi)^(-n))/(2*phi-1)

}

Try it out! For exampe, I get the following results in the following for the following cases:

> sapply(0:19, fibo)

[1] 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377 610 987 1597 2584 4181

> fibo(57)

[1] 365435296162

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: