Solving Peg Solitaire with efficient Bit-Board Representations

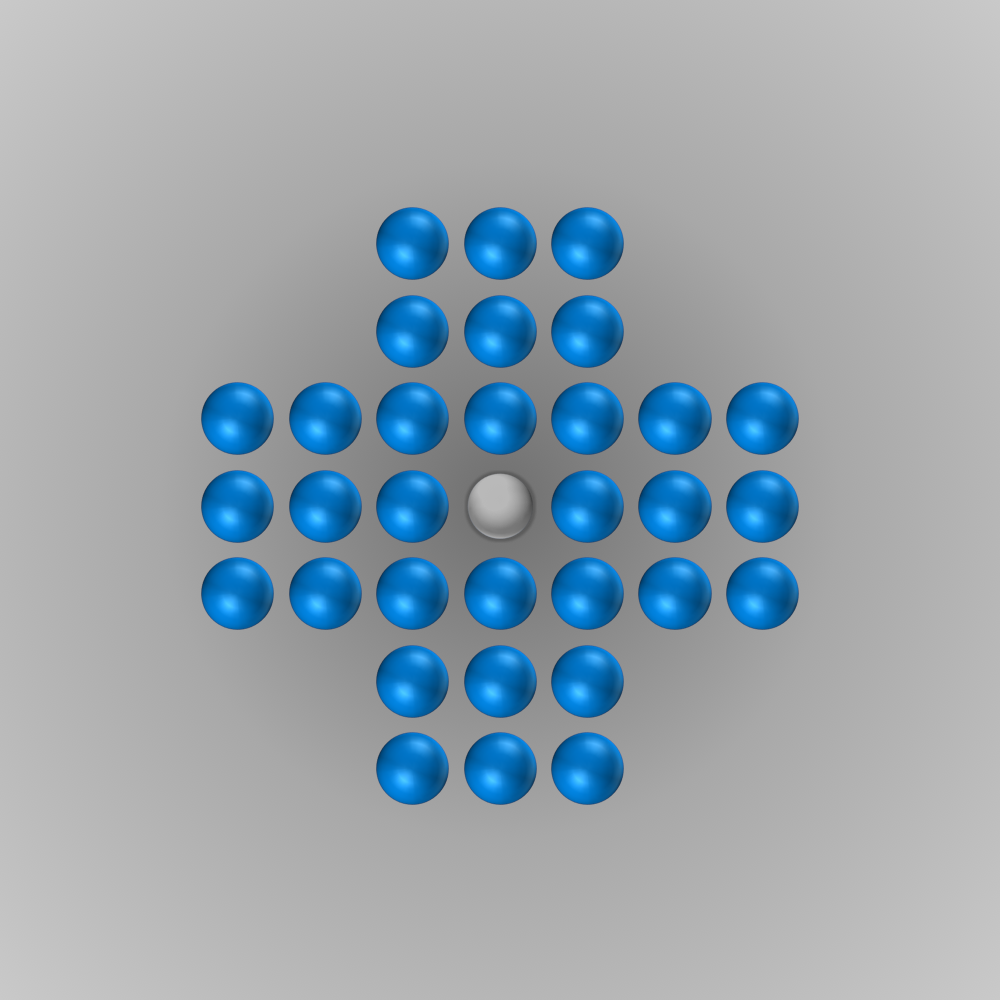

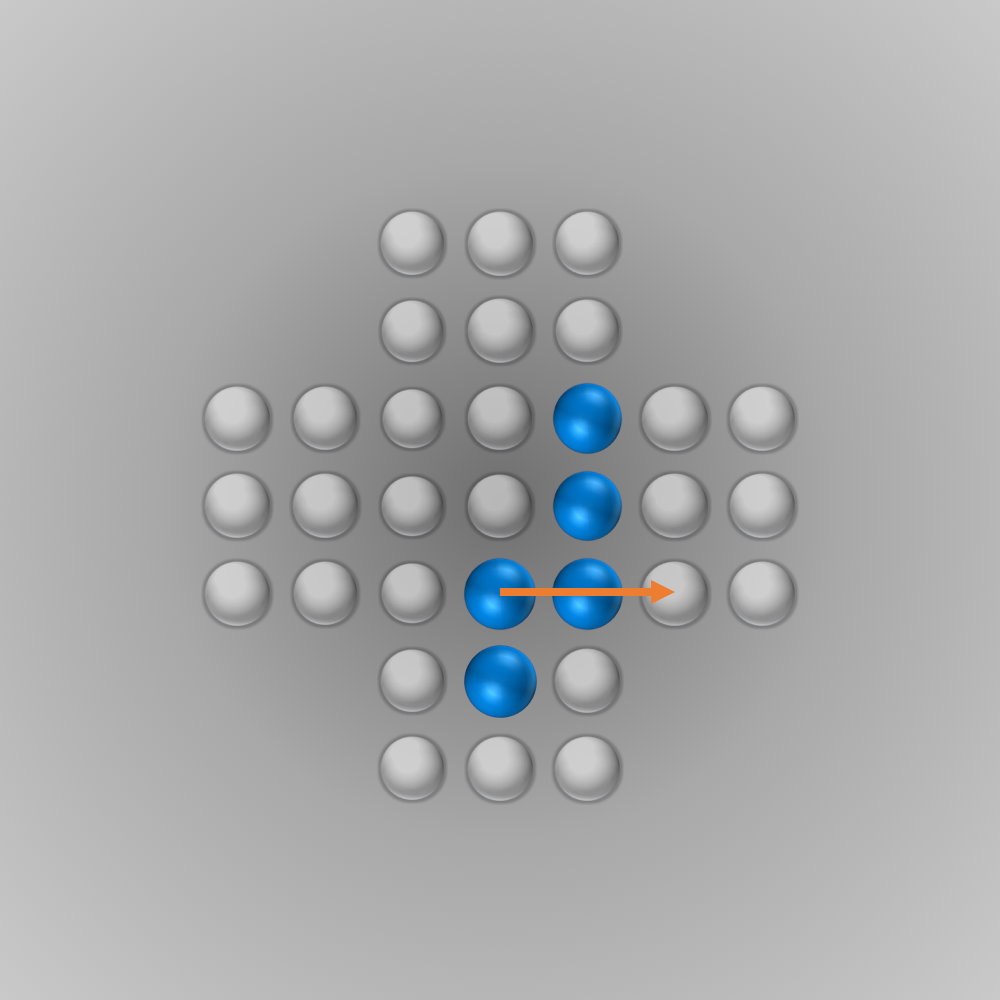

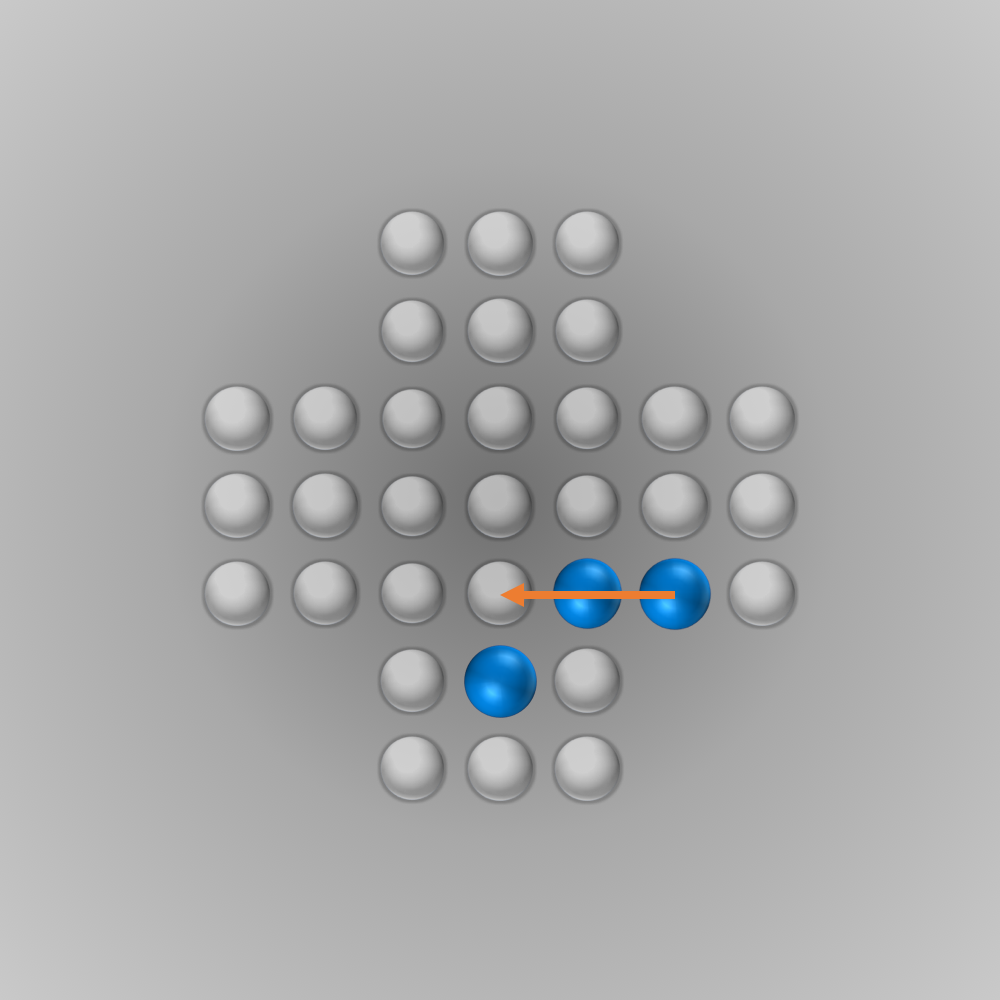

Many of us know the board game peg solitaire and might even have one of its many variants at home. Peg solitaire is a one-player game played on a board with \(n\) holes and \(n-1\) pegs. The number of holes depends on the board variant. For example, the English variant consists of 33 holes, while the typical diamond variant consists of 41. The rules of the game are relatively straightforward. In each move, the player selects one peg and jumps – vertically or horizontally, not diagonally – with this peg over a directly neighboring one into an empty hole. The neighboring peg is then removed, leaving an empty hole. So, in each move, one peg jumps two holes further, and the peg in between is removed. Once no move is possible any longer, the game is over. This is the case when no pair of orthogonally adjacent pegs or if only one peg is left. In the latter case, the game is won. As shown below, the English variant has one additional rule: To win, more is needed than only one peg being left in the end; this peg must also be located in the center of the board. The English variant is shown in the figure below.

Even though the game’s rules are pretty simple, finding a solution is not trivial. Many players need several attempts to find the solution for the English peg solitaire. The solution for the diamond-shaped board is even more tricky.

Solution for the English Peg Solitaire

When I embarked on my programming journey a few years back, English peg solitaire was among my first projects. Frustrated by my inability to solve the game, I decided to take matters into my own hands and write a solver. The code, which you can find at the end of this post, may not be the most elegant or efficient, but it manages to find a solution in under a second. I attribute this success to a stroke of luck with the standard move ordering I used. Interestingly, a slight change in the move ordering significantly increases the solver’s runtime to several hours.

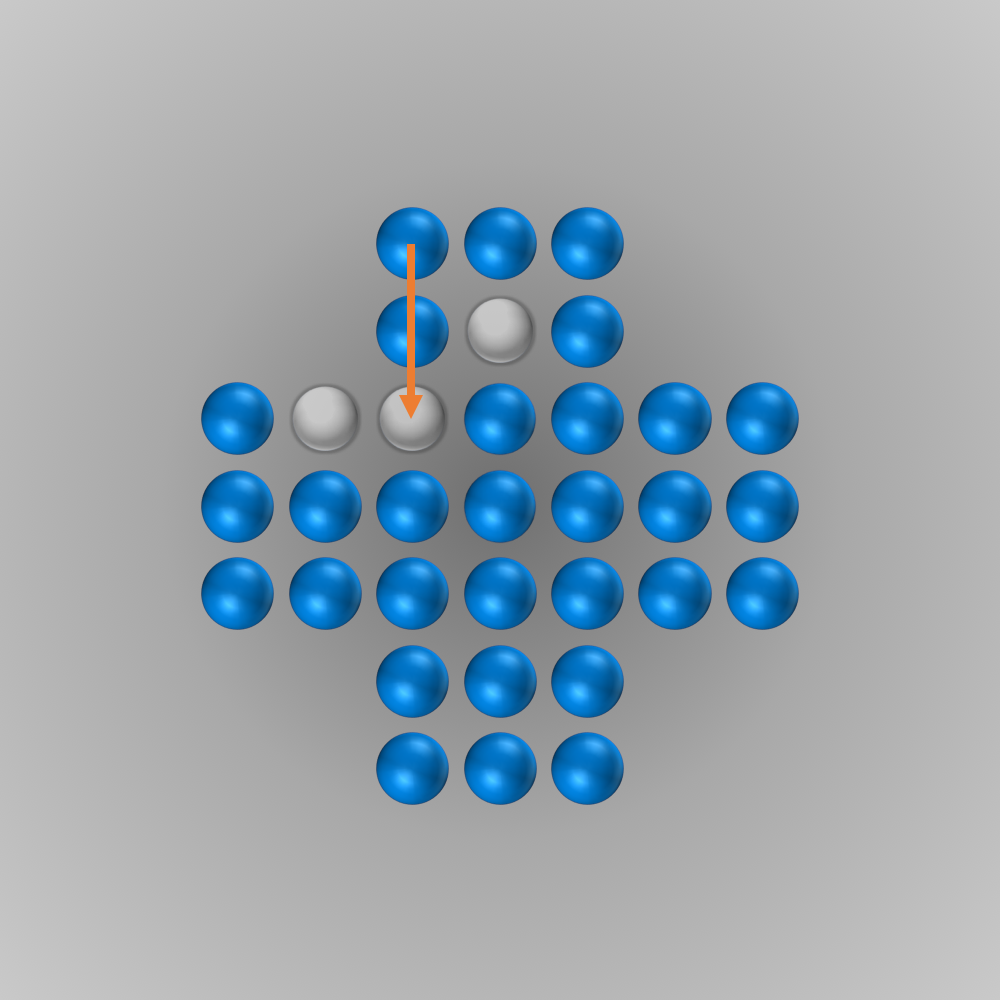

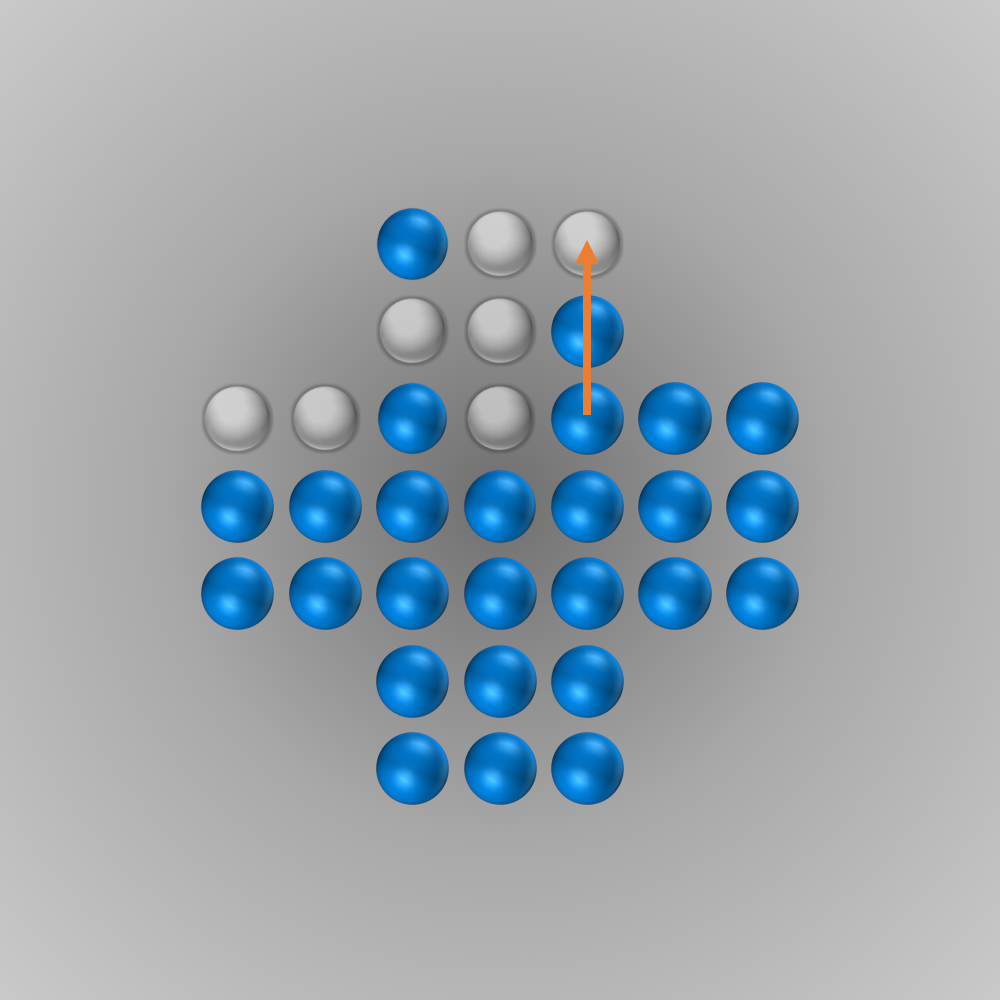

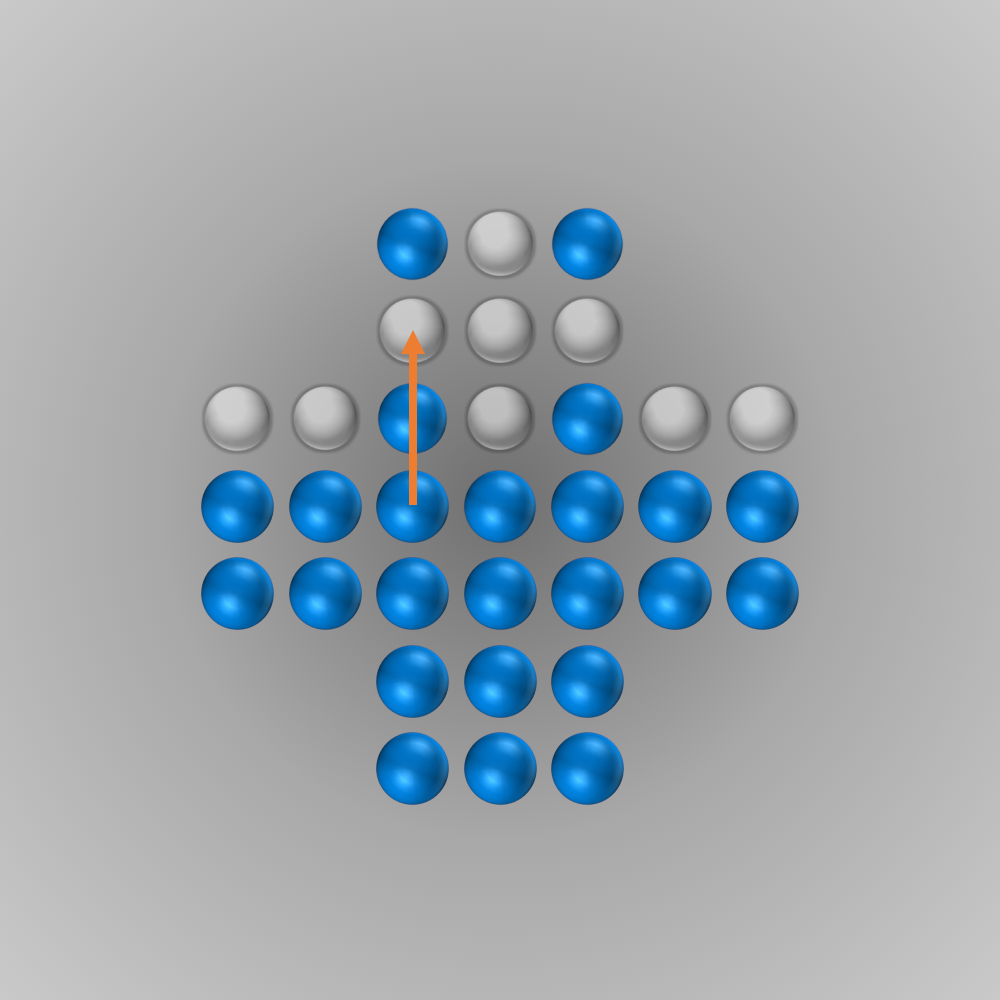

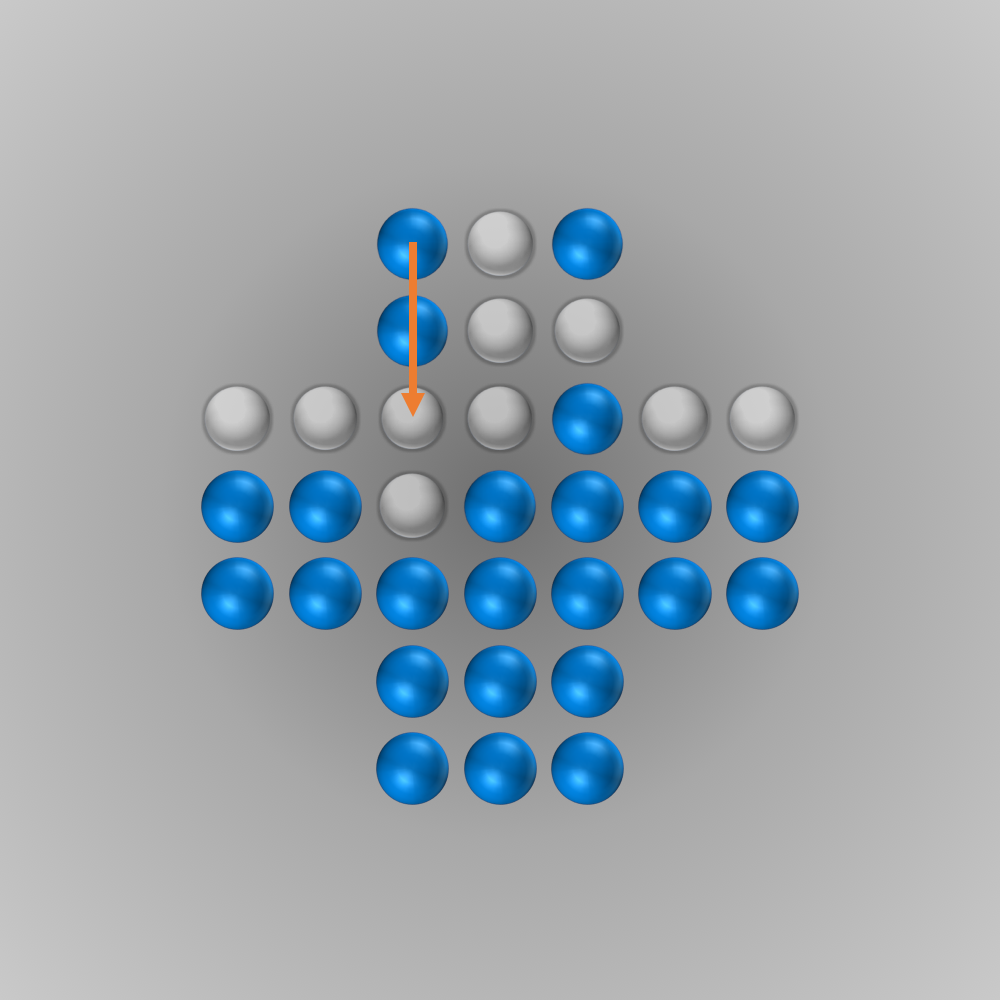

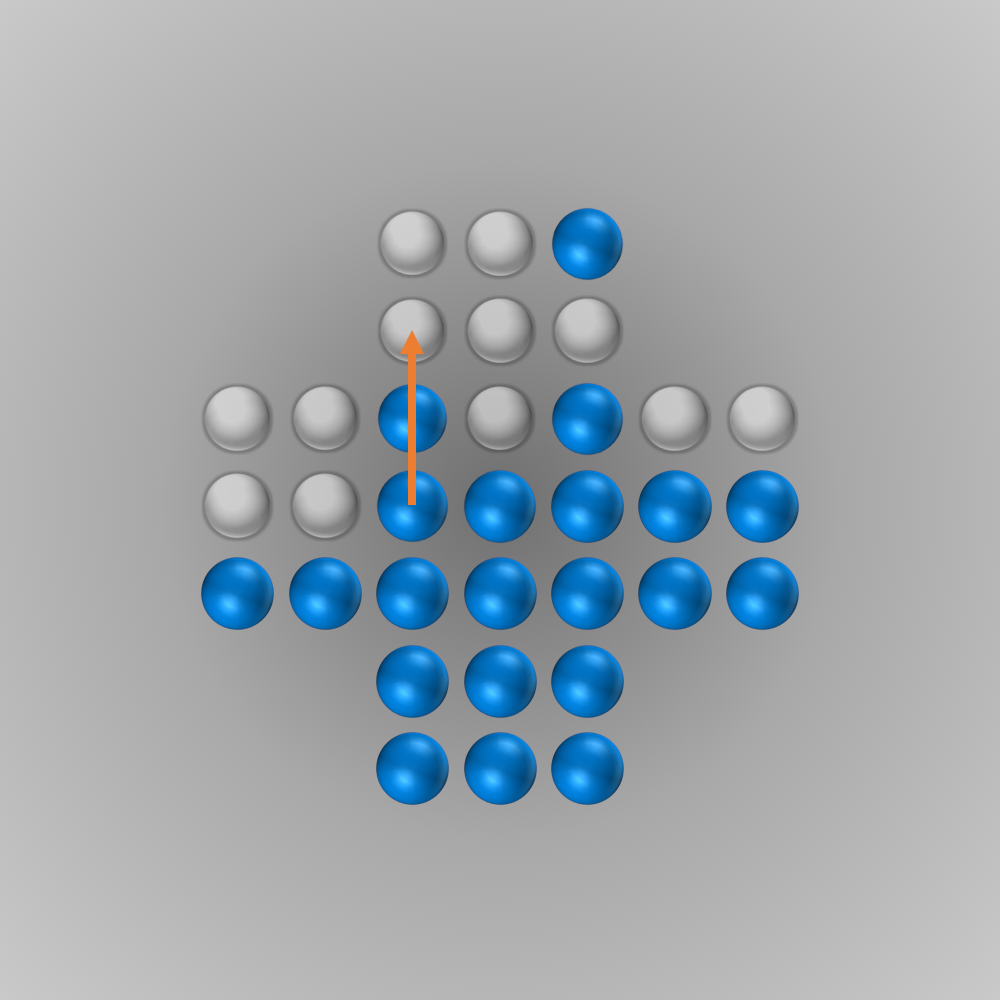

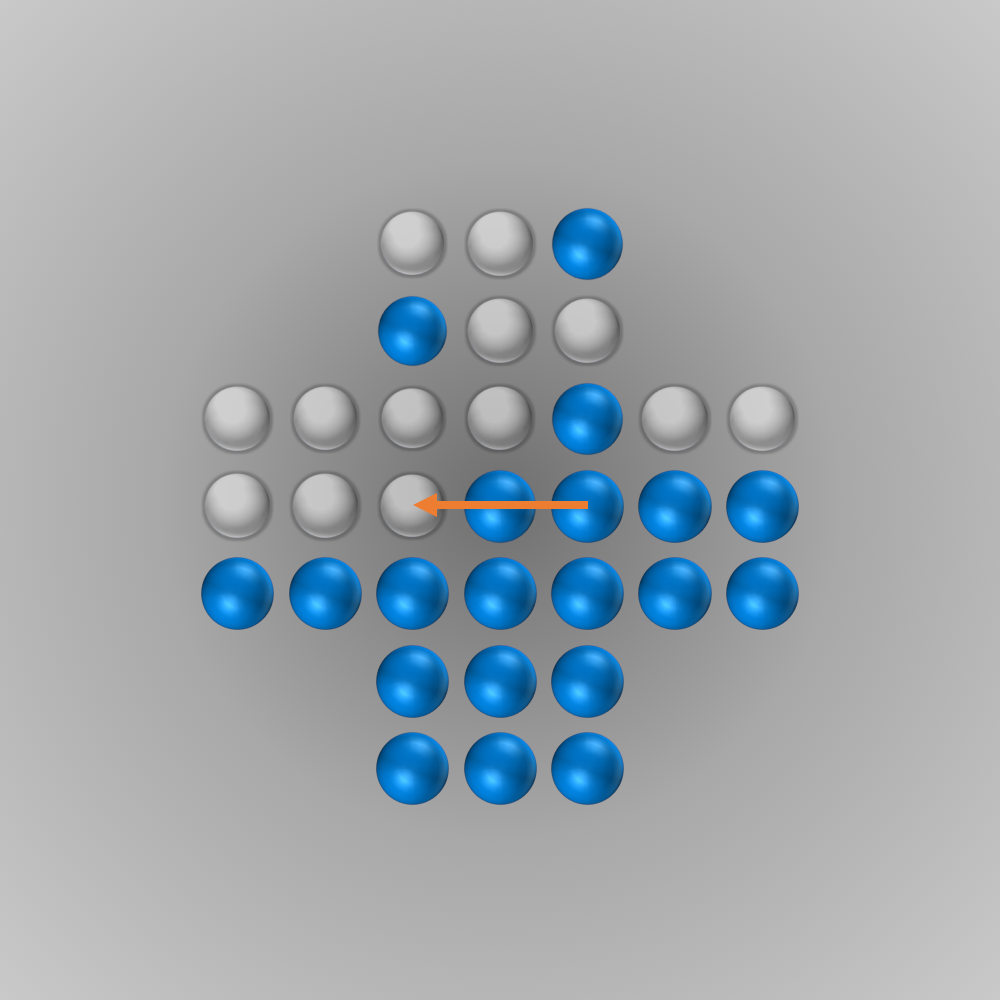

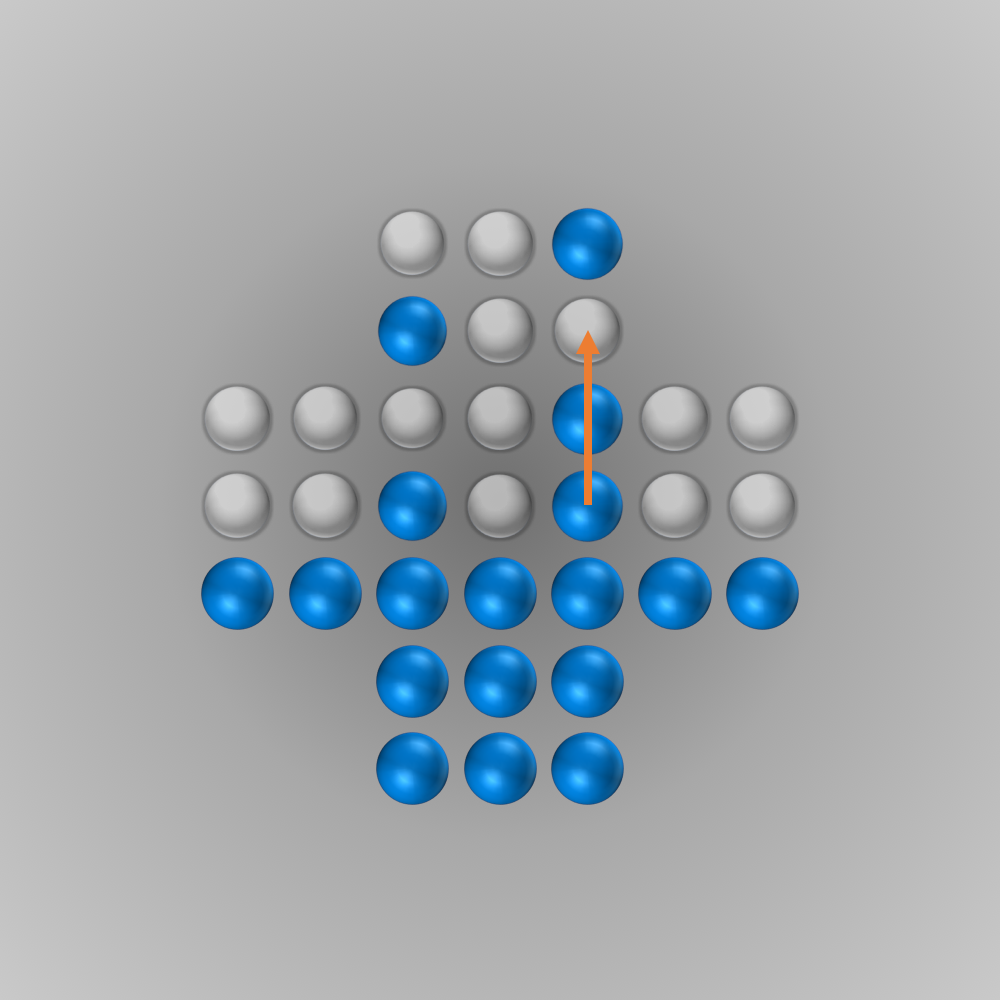

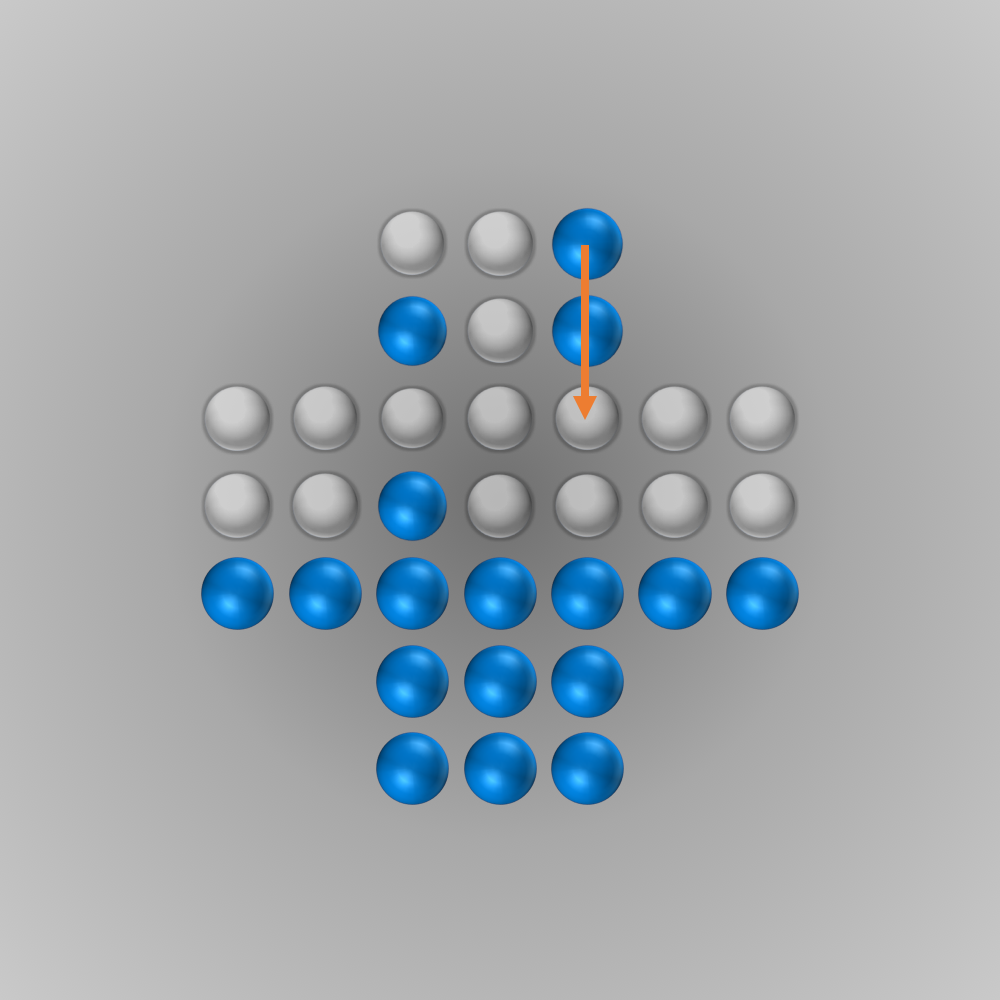

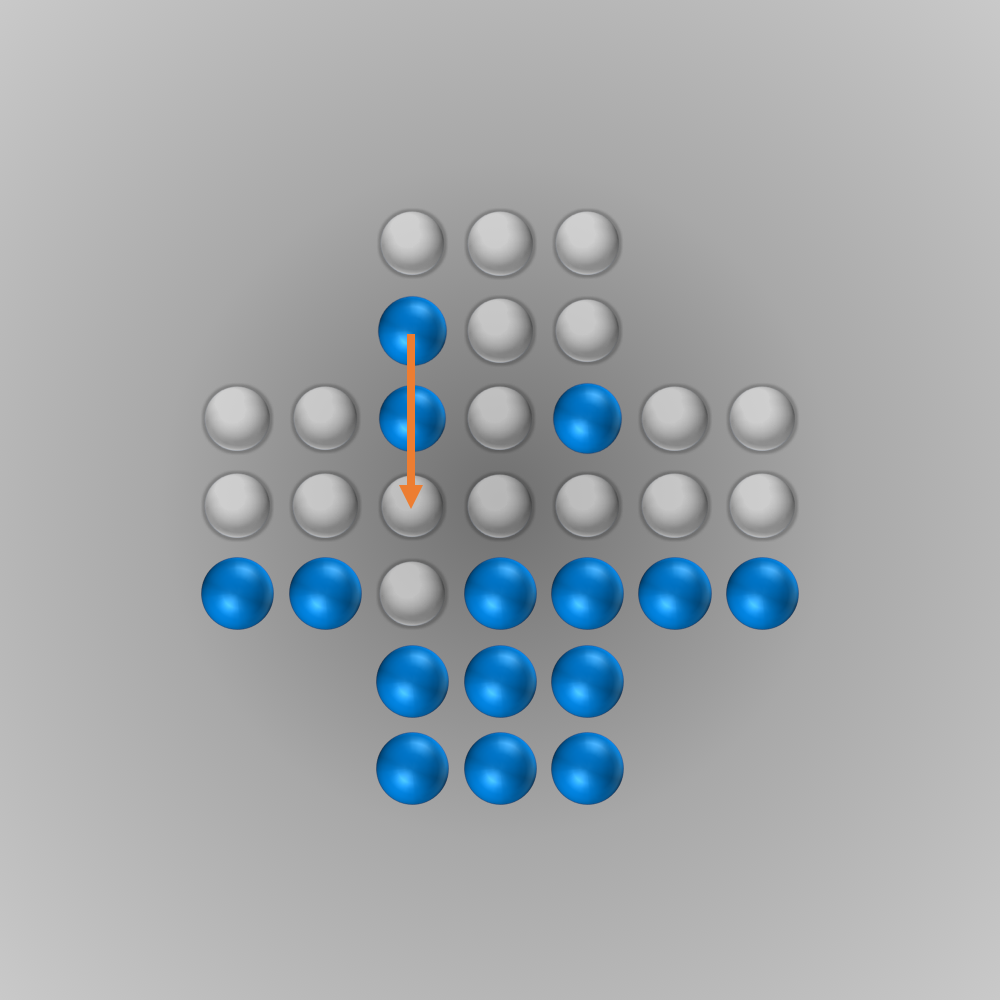

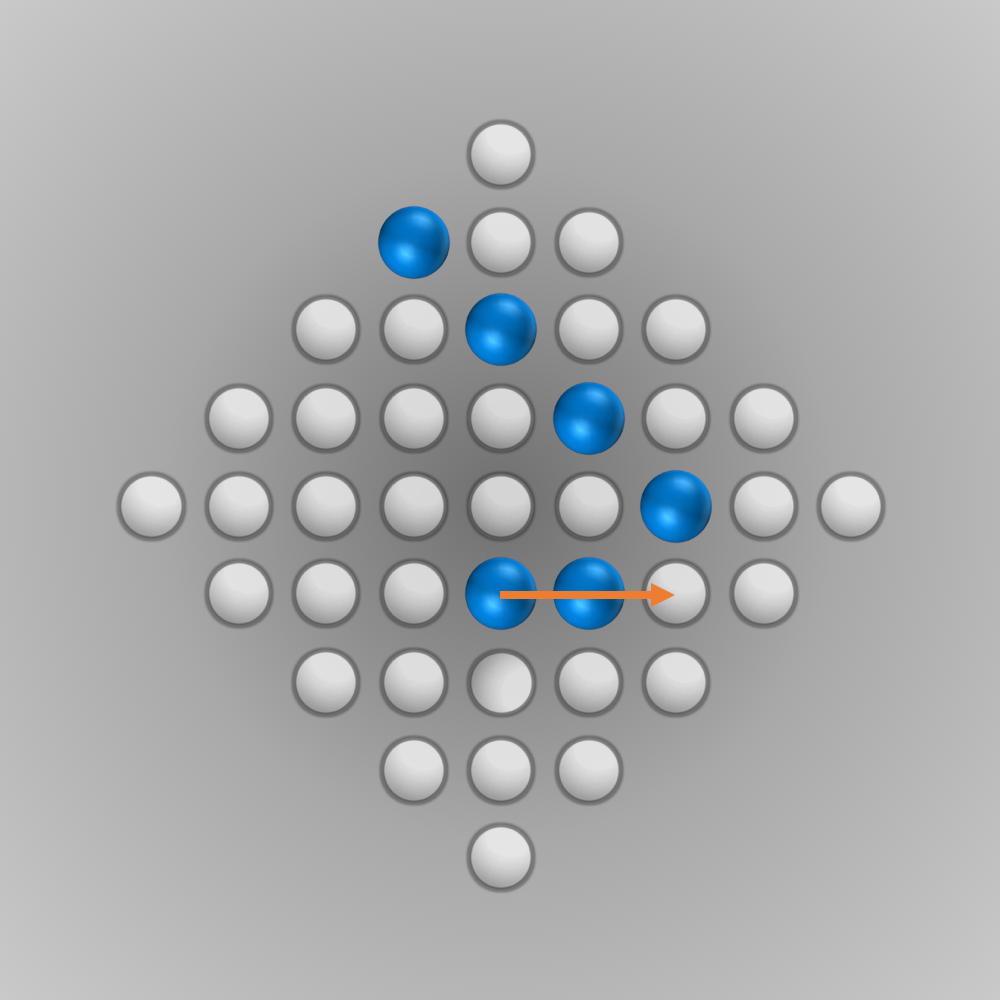

The solver gave me the following solution:

Recently, I again stumbled across peg solitaire when I saw a different board with the shape of a diamond. This stirred my interest in the game again, and I spent several hours writing a solver using bit boards and some other enhancements for this board, as described in the following section.

Efficiently Solving the Diamond-41 Board

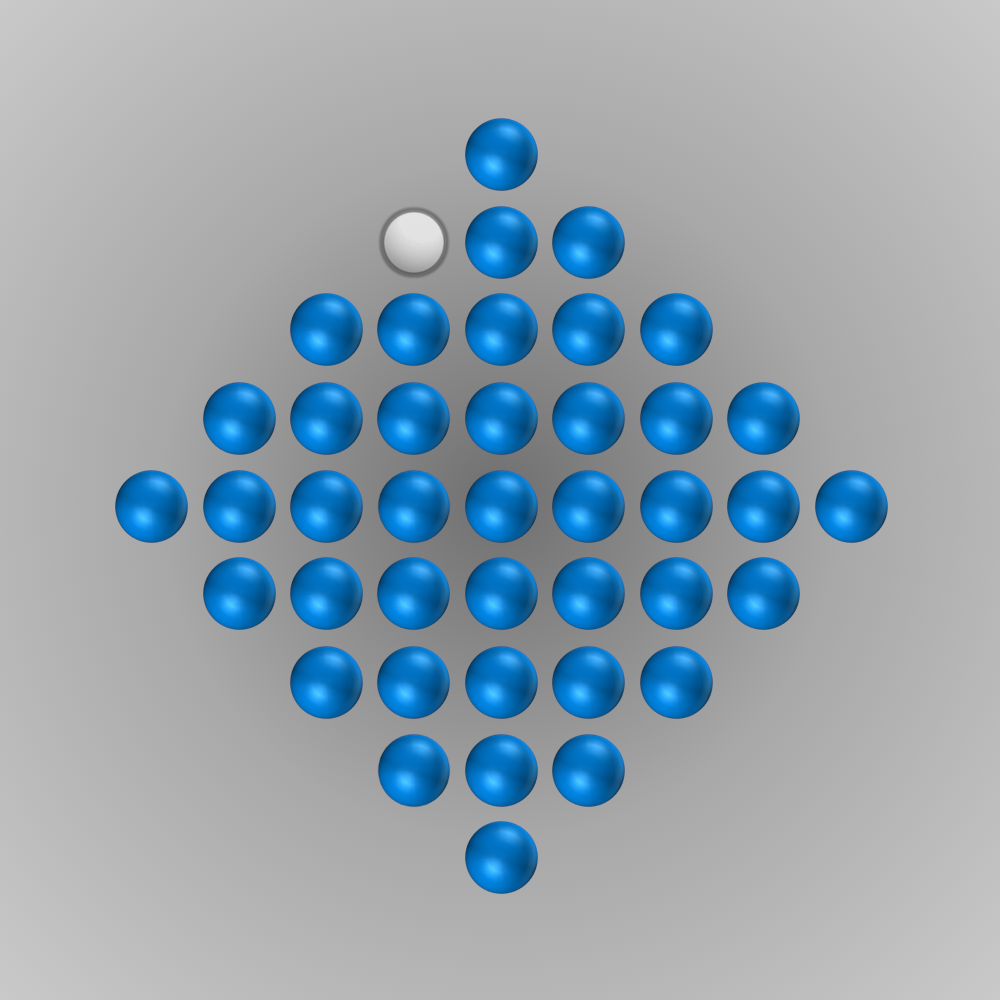

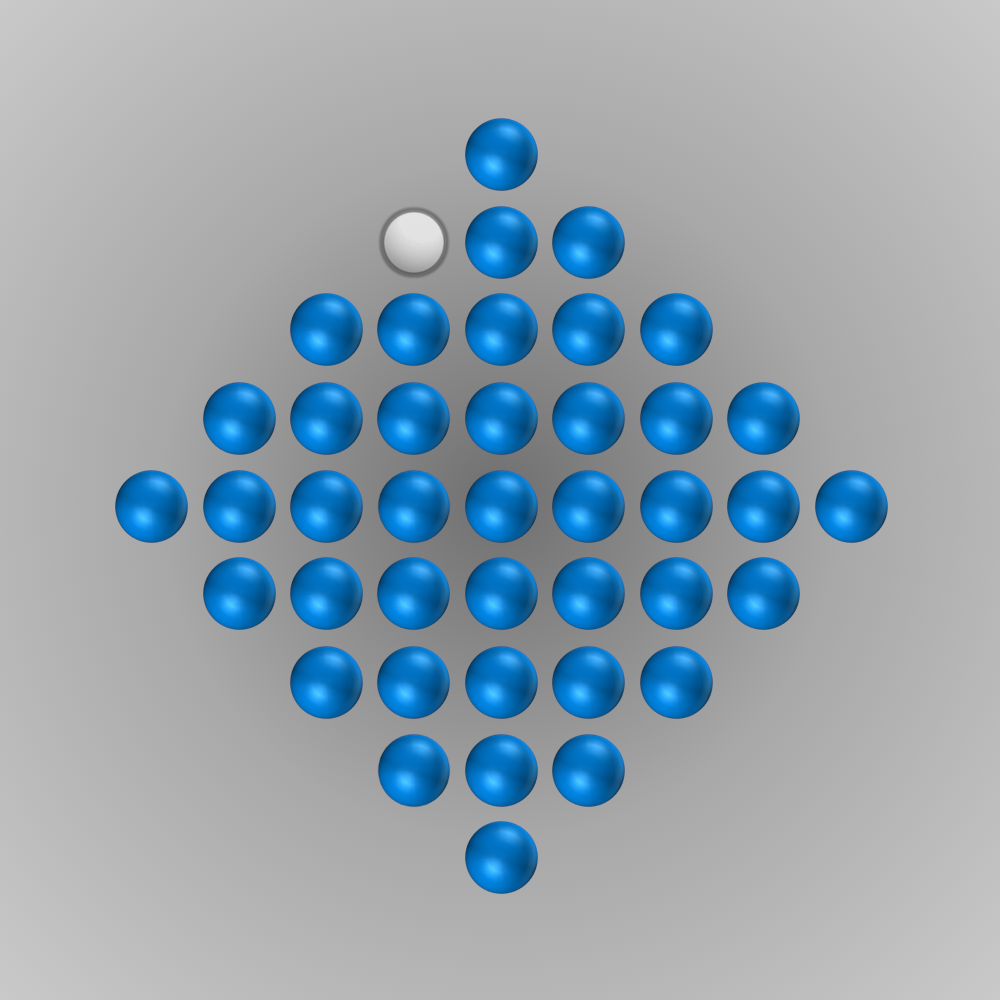

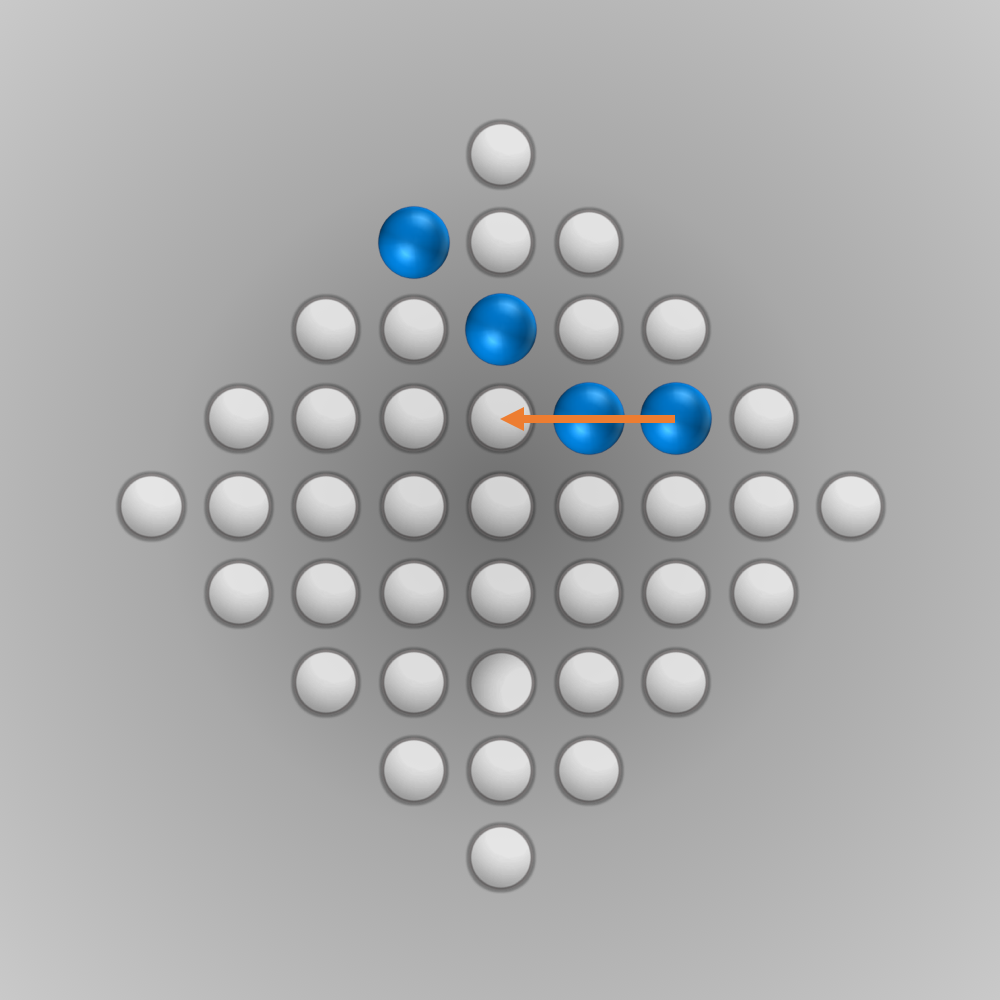

As the name suggests, the Diamond-41 board consists of 41 holes. As I was told – in contrast to the English variant – the only initial empty hole is not located in the center of the board but has to be placed at a slightly different position to be able to solve the game (as I found later, the solver was not able to solve the game for an initially empty hole in the center of the board). The initial position is as follows:

In the beginning, only two moves are possible. Since there are many corners on this board, it isn’t easy to find a solution where only one peg is left over at the end. Also, for backtracking algorithms, the computational effort is enormous to solve this problem. Without advanced approaches, an algorithm could run for many days until a solution is found.

Bit-Boards

One significant improvement of a classical algorithm can be achieved when, instead of arrays, so-called bit-boards are used to represent a position. Using bit-boards is especially easy for peg solitaire since each hole can either be empty (binary 0) or filled with a peg (binary 1). In this way, only 41 bits are required to encode any board position. Hence, a 64-bit variable is sufficient. There are also enough bits left over which can be used to encode the board’s boundary. As we will see later, this is important for checking if a move is within the allowed limits. Bit boards have the advantage that the whole board can be processed at once with bitwise operations. Suppose the encoding of each hole is done suitably. In that case, many operations (such as generating valid moves for each position, mirroring the board along a particular axis, counting pegs, etc.) can be executed with minimum CPU cycles. Additionally, the representation is memory efficient, so positions can be easily stored in a hash table or other data structures.

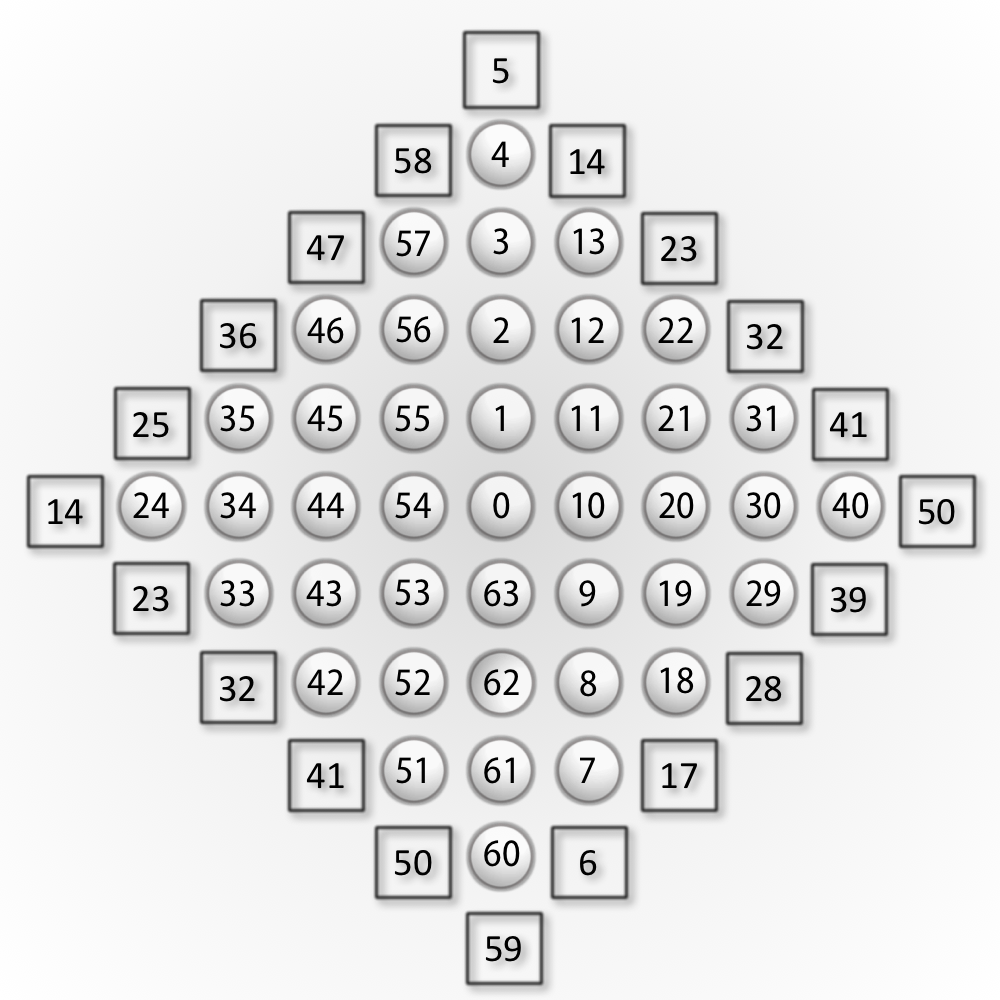

I designed the following layout for the bit-board representation of the Diamond-41 variant of peg solitaire.

Each number represents the corresponding bit in the bit-board. The center hole is placed at bit 0. The squares in the above diagram show the boundary of the board. Moves are not allowed to end up in any of these bits. Note that many boundary bit-numbers appear twice in the diagram. This is due to the unique layout, which I will explain in the following. However, having a separate bit for every point on the boundary is unnecessary since it is only used to check if a move leaves the board.

The advantage of this arrangement is that all pegs can be easily moved vertically or horizontally. For example, a bitwise left rotation of the board would move all pegs vertically by one. Accordingly, pegs are moved down by a rotation of one to the right (or left rotation of -1) and moved horizontally by bitwise rotations of the bit-board by 10 and -10. As we will see, this is especially helpful when we want to find all possible moves. This move generation can be done in very few CPU cycles, even for complex board situations. Furthermore, mirroring the board along the vertical and horizontal axes can also be done comparably fast. The only tradeoff is that rotations of a position can only be computed with some extra effort. One solution for this problem could be consistently maintaining two bitboards: one for the original position and one for a rotated position (by 90 degrees). All other symmetric positions (8 overall) could be constructed with vertical/horizontal flips.

For example, the remaining number of pegs can be computed with an efficient function that counts the number of set bits in a bit field. Since we are usually interested in counting the remaining pegs after no move is possible anymore, there are typically not too many pegs left, and the following function computes the number very fast:

int bitCount(uint64_t x) {

int c = 0;

while (x != ZERO) {

x &= (x - UINT64_C(1));

c++;

}

return c;

}If only three bits are set in a bit-field, above function would only require 3 iterations in order to count the set bits.

Move Generation

The method to compute all the possible moves for a given board position b is even more critical. All possible moves in one direction (in total four directions) can simply be computed with:

uint64_t mv = rol(rol(b, dir) & BOARD & b, dir) & BOARD & (~b);where b is an arbitrary board position, rol is a bitwise rotation left (implemented with some inline assembler), dir is the specified direction (+1 for up, -1 for down, +10 for right, -10 for left) and BOARD is a bit-mask which masks all 41 holes of the board. The variable mv contains all the target holes for the allowed moves in the specified direction. After all the possible moves (in mv) for a direction dir are known, each move can be performed with a few bitwise operations. We can extract the next move, which should be performed with:

// Get next move from all possibilities mv

uint64_t x = ((mv - 1) ^ mv) & mv;To perform the move, we have to set a peg to the target position, we have to remove the “jumped-over” peg, and then remove the peg from the old position:

// perform move

b |= x; // set peg at new position

b &= ~rol(x, -dir); // remove jumped-over peg

b &= ~rol(x, -2 * dir); // remove peg from old positionUndoing a move can be done accordingly. All of these steps require only a few bitwise operations. A solver with an array-based data structure for the board would likely perform the moves slightly faster, but the move generation itself (which is commonly an expensive task) is done much quicker with this bit-board design.

Move Ordering

Finding all possible moves in one direction is as simple as that. However, I added a few lines of code that allow for better move ordering, which is essential for finding a solution faster. With a standard move ordering, the search might take many days. Hence, it might be reasonable to spend CPU time sorting the moves to try more promising ones first. For example, the move ordering defers moves that end up in the corners of the board since it is typically not easy to get out of the corner again. Also, other types of moves are ordered to the back of the list if they do not appear promising.

Symmetries & Transposition Tables

When traversing the search tree, many positions repeat since permutations of a move sequence can lead to identical positions. Furthermore, the Diamond-41 board is symmetric, having mirror and rotation symmetries. Hence, we can save computation time if we know the values of repeating positions and their symmetric equivalents. The value of a position is the minimum number of remaining stones of the final state when an optimal move sequence is performed – starting from this particular position. For example, if we know that position \(b_1\) has a corresponding value of \(3\), then a position \(b_2\), which is identical to \(b_1\) after rotation, will also have a value of \(3\). If we store the already known value of positions, we could save some computation time when we observe a (symmetrically) equivalent position again by retrieving and returning the stored value. With such an approach, we could prune the search tree significantly and avoid redundant calculations without losing any information. A common technique used for board games, such as chess, checkers, etc., is the utilization of transposition tables. The idea is to define a suitable hash function that takes the board position (and no historical information of the move sequence that led to this position) and returns a hash value that can be mapped to an index to store the game-theoretic value of a position in a hash table. When we observe a new position, we can calculate the corresponding hash and check if there is an entry in the hash table. If we find an entry, we are lucky and can stop the search for the current position and cut off the connected sub-tree. If not, we have to traverse the connected sub-tree and then store the retrieved value afterward in the table. For our problem, an entry in the table could look like this:

struct HashElement {

uint64_t key;

int value;

};Since we are not performing an Alpha-Beta search or similar, there is no need to store further information besides a key and a value. Note that we also have to store a key, which is simply the position itself in this case, since many board positions will map to the same hash table index. This is because the hash function is typically not injective, and the modulo operation is required to break down the hash value to an index. Since it is impossible to prevent collisions, it is always necessary to compare the key of the stored element with the current board position. From this problem, another question arises: What do we do if we want to store a key-value pair in the transposition table, but the corresponding slot is already occupied by another position? The answer for our case is simple: We overwrite the older entry in the table. This approach is often sub-optimal since we might destroy valuable information (especially the values of positions located close to the root node, which was expensive to compute and could be replaced by those of positions that are very close to a leaf node of the tree). However, in our case, it still worked decently. Commonly, the size of the hash table is chosen to be a power of two since the modulo operation to map a hash value to a table index turns out to be simply a bitwise AND:

int hashIndex = ((int) hash & HASHMASK); // = hash % pow(2,n)where HASHMASK is the size of the table minus one (\(2^n - 1\)). One last detail has to be mentioned: How do we define the hash function? Typically, so-called Zobrist keys are used for many board games. These are a clever way to encode a position by XOR-ing (exclusive or) random integers. One random number is generated initially and then used throughout the search for each possible move. Whenever a move is performed, the current Zobrist key \(Z\) will be linked by an XOR and the corresponding random number of the move. This approach utilizes the associative and commutative property of the exclusive or as well as the involutory property (\(x \oplus x = 0\) ). In my program, I did not use Zobrist keys for simplicity reasons (but they can also be implemented with relatively little effort). Instead, I use a simple hash function of the form

/*

* Function to compute the hash for a 64bit variable. Maybe Zobrist keys would

* // work better (has to be investigated in future).

****/

uint64_t getHash(uint64_t x) {

x = (x ^ (x >> 30)) * UINT64_C(0xbf58476d1ce4e5b9);

x = (x ^ (x >> 27)) * UINT64_C(0x94d049bb133111eb);

x = x ^ (x >> 31);

return x;

}which is based on this interesting blog post by David Stafford.

Finally, the Solution of the Diamond-41 Peg Solitaire Board…

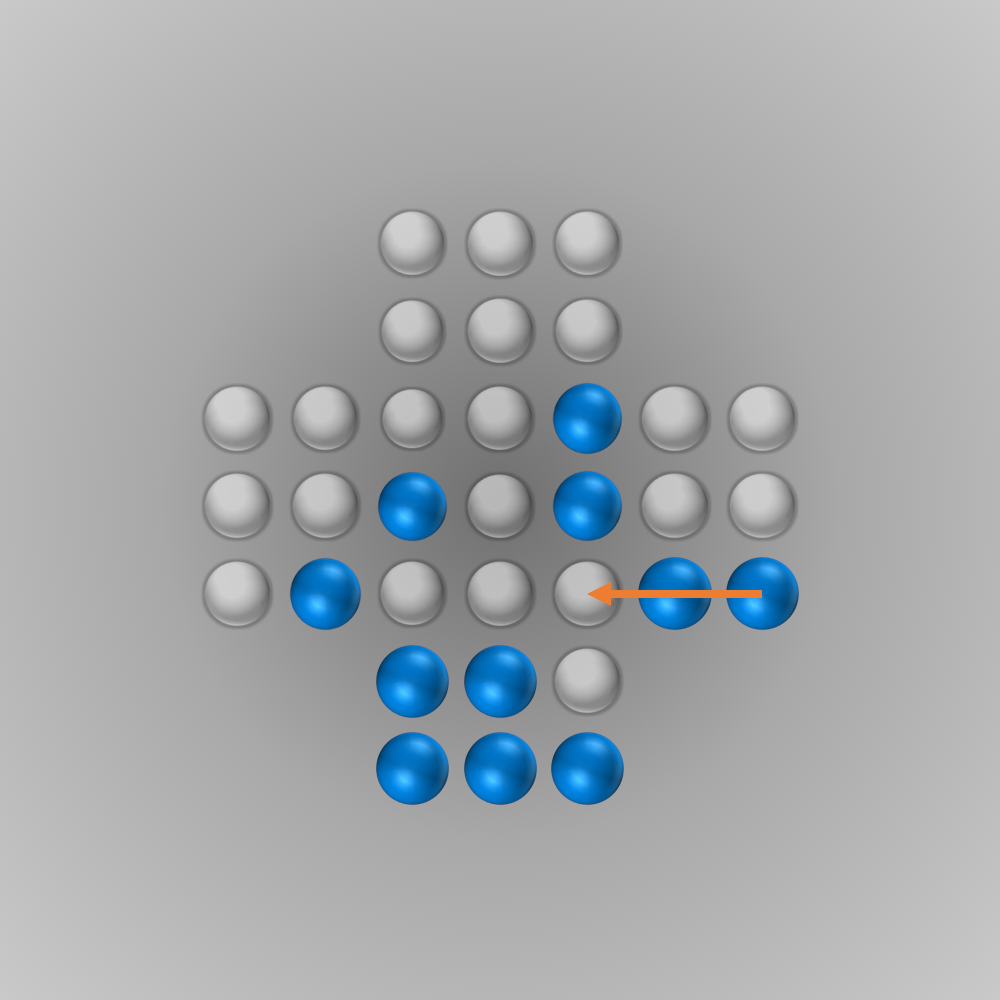

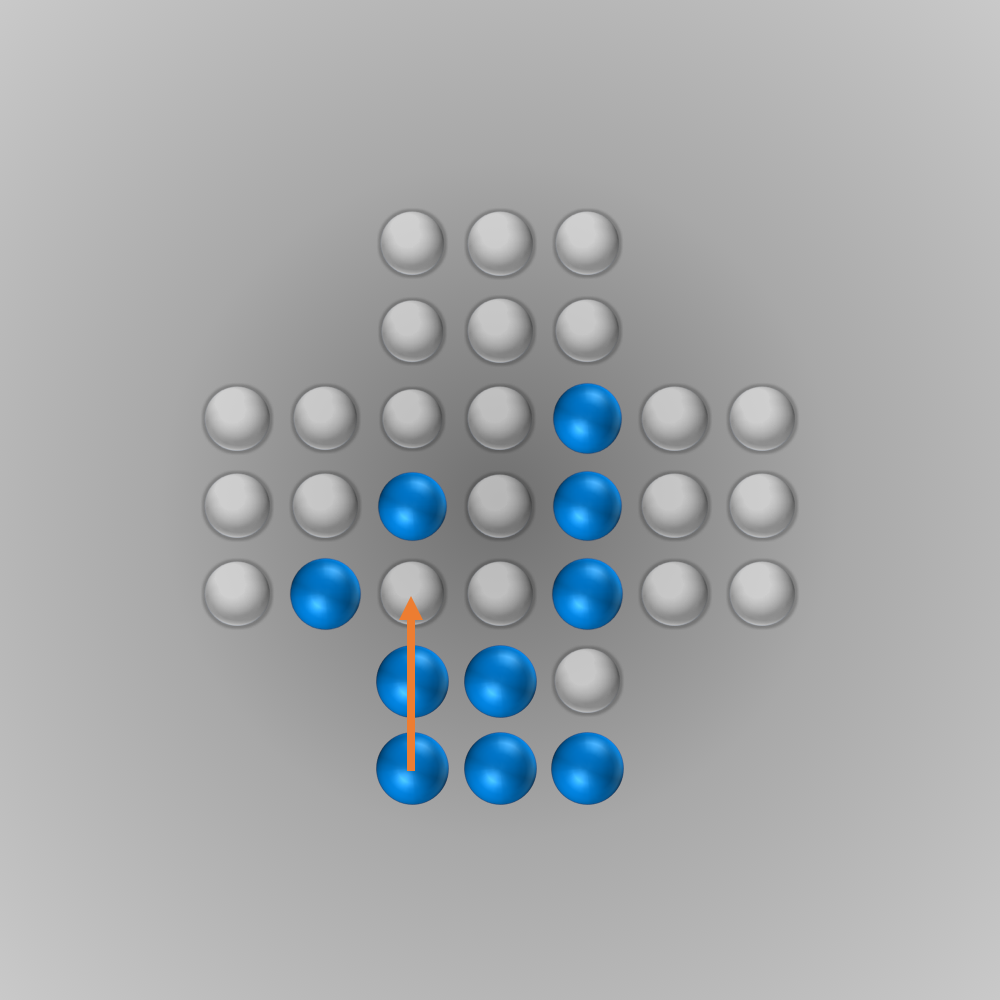

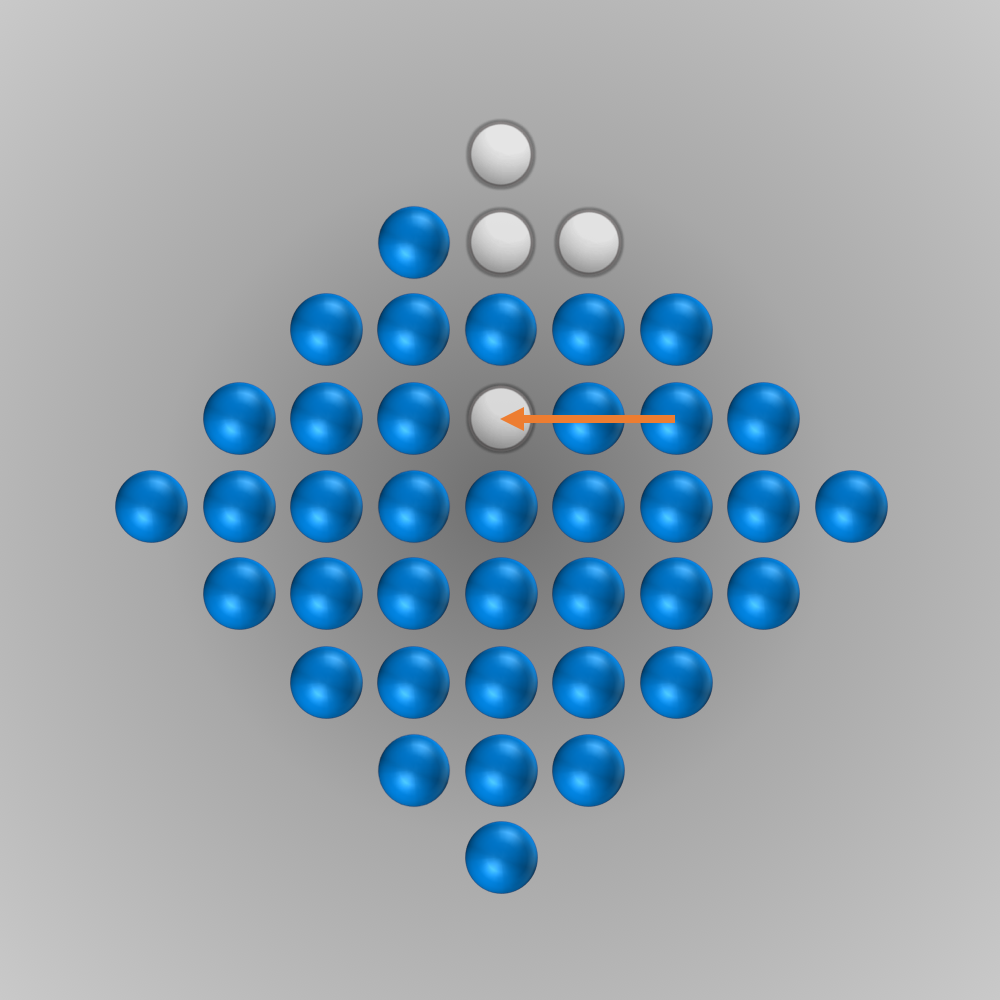

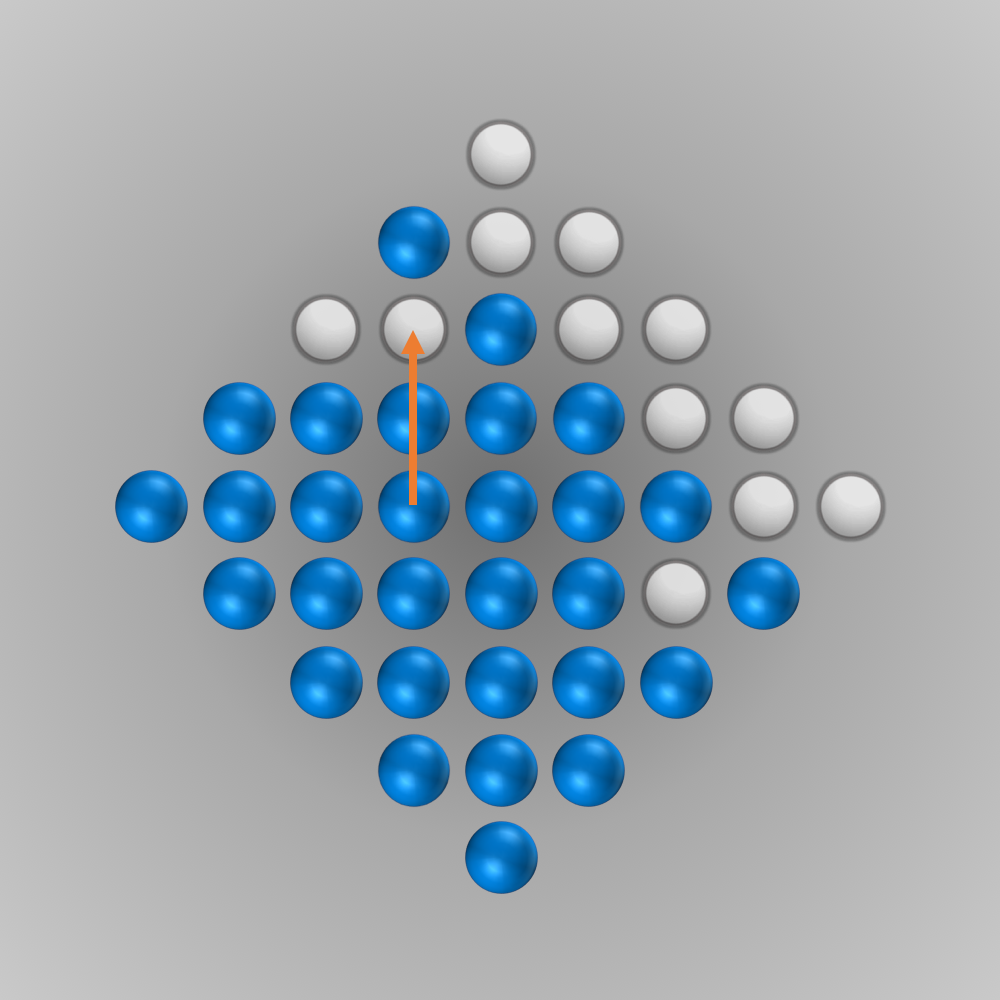

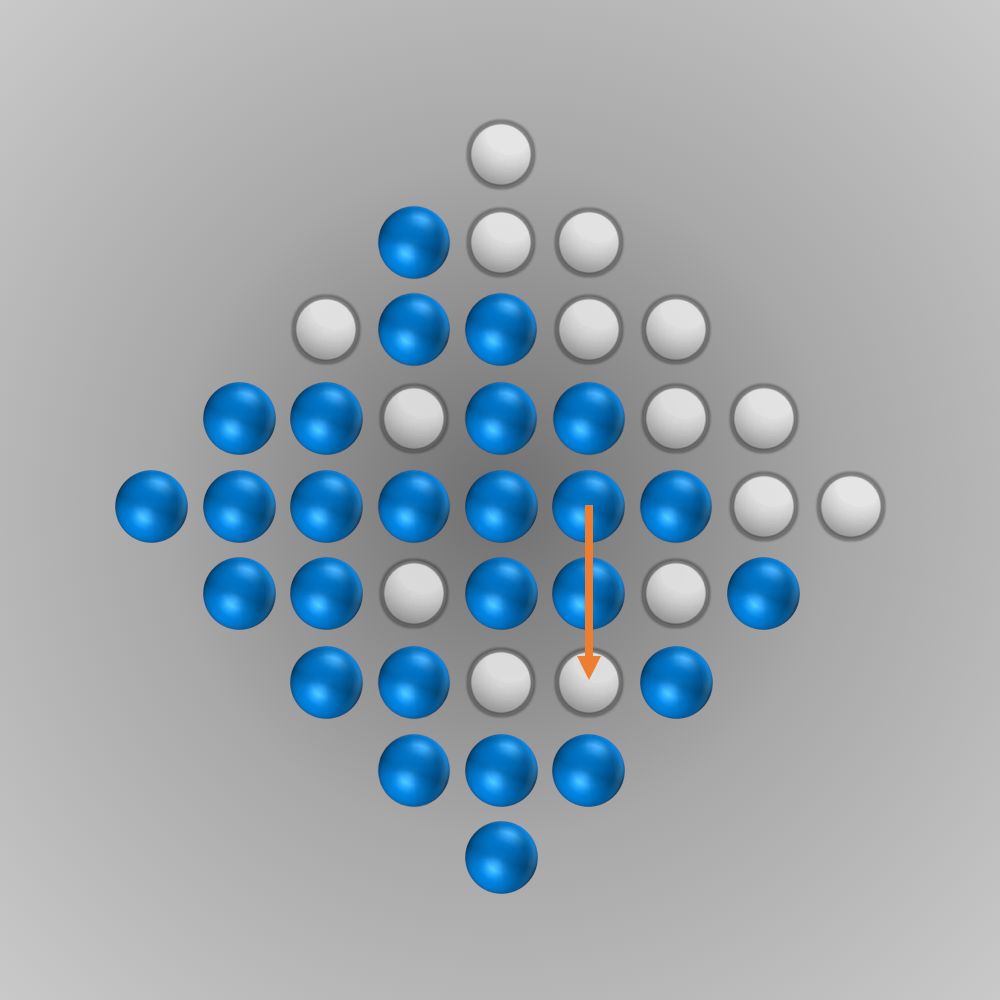

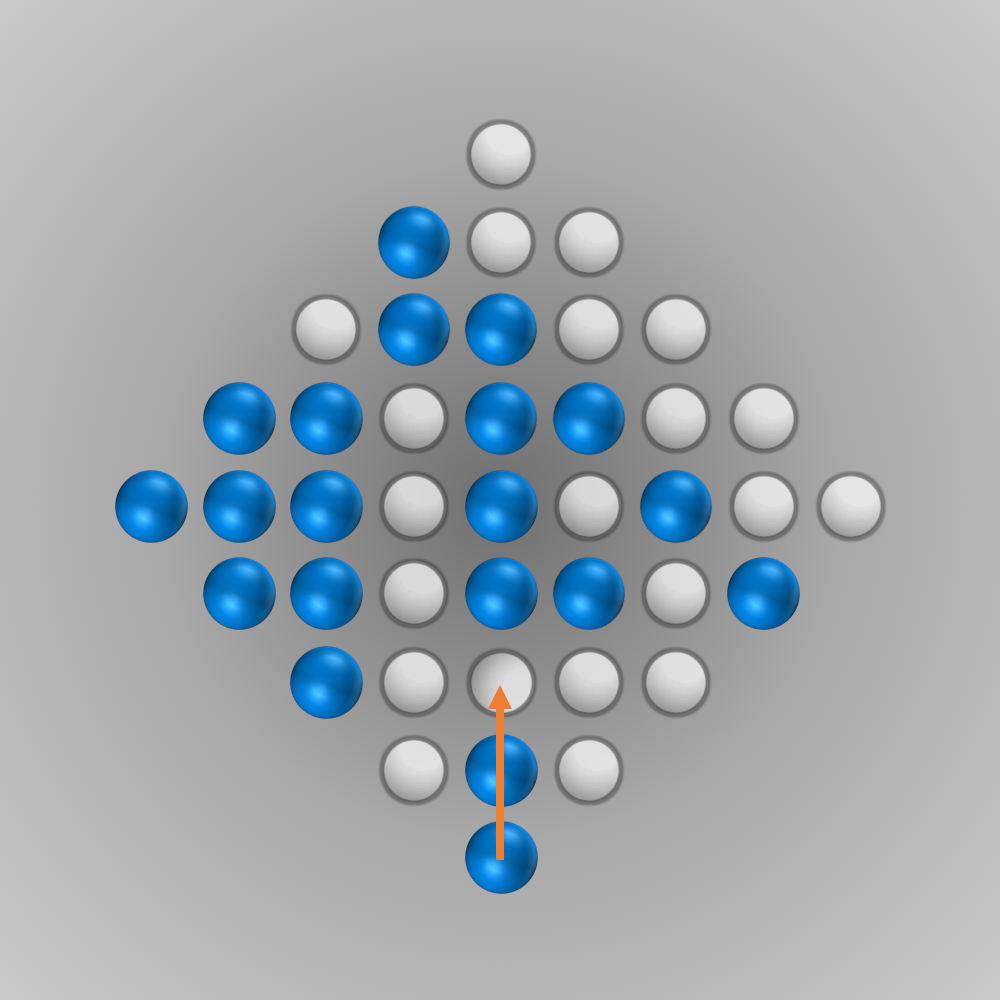

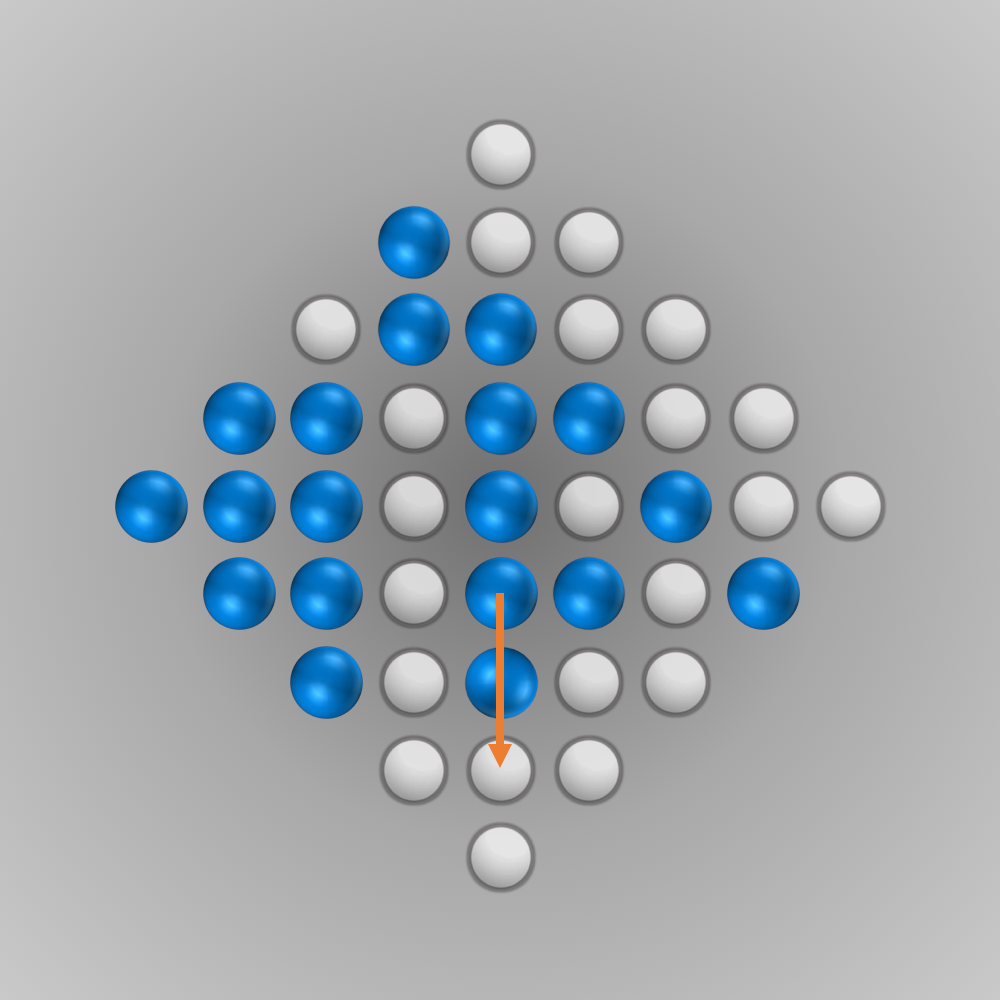

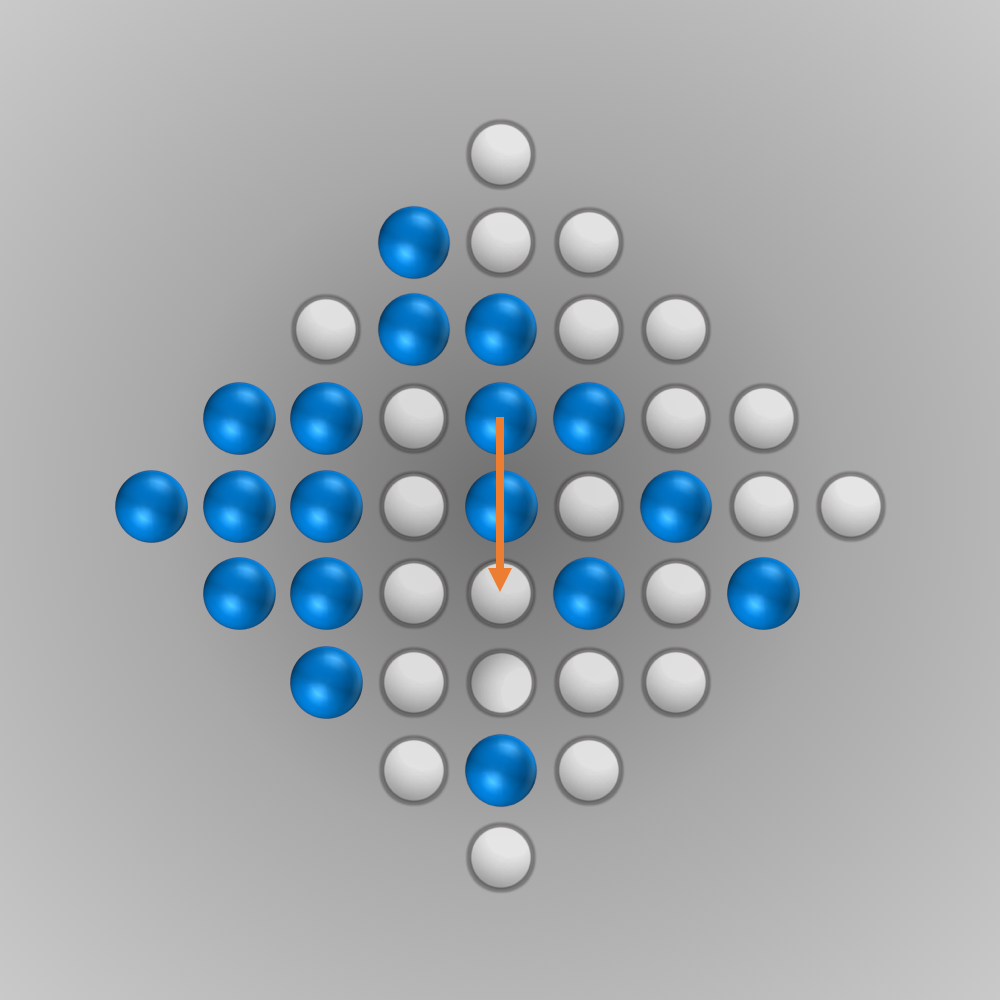

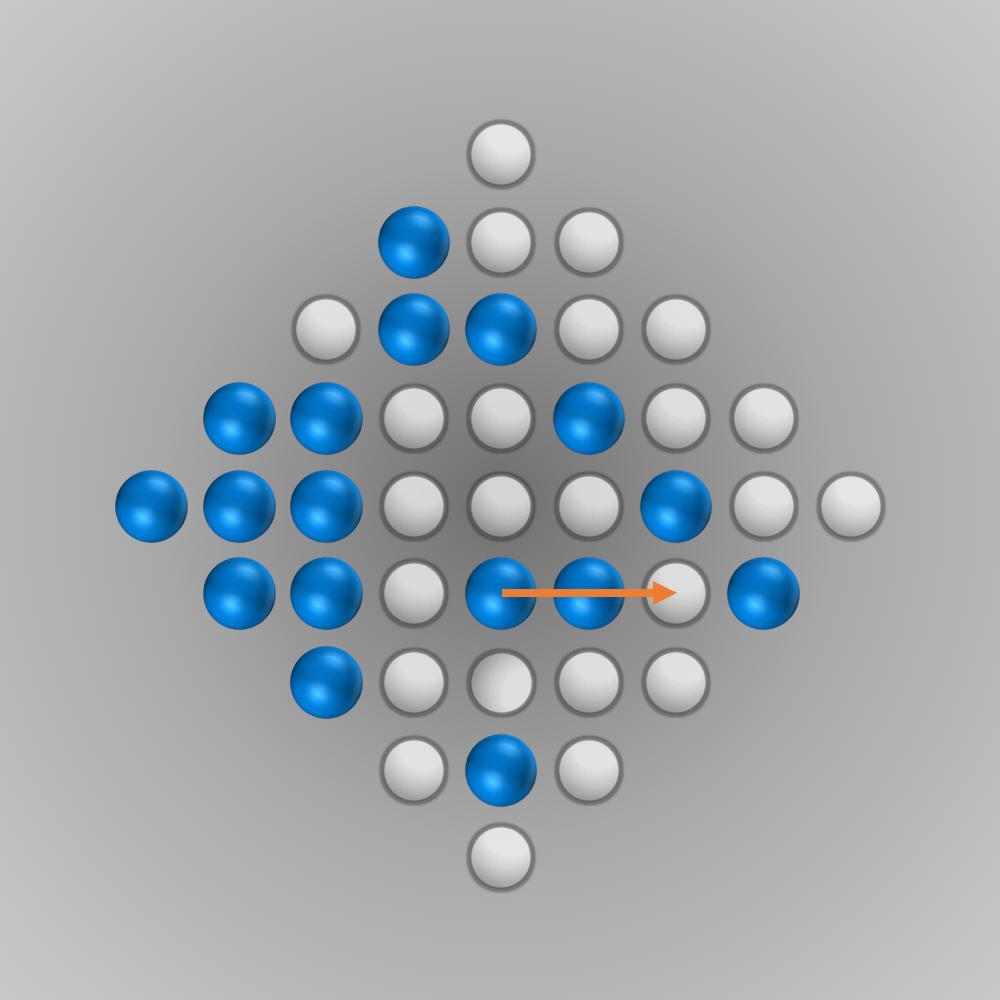

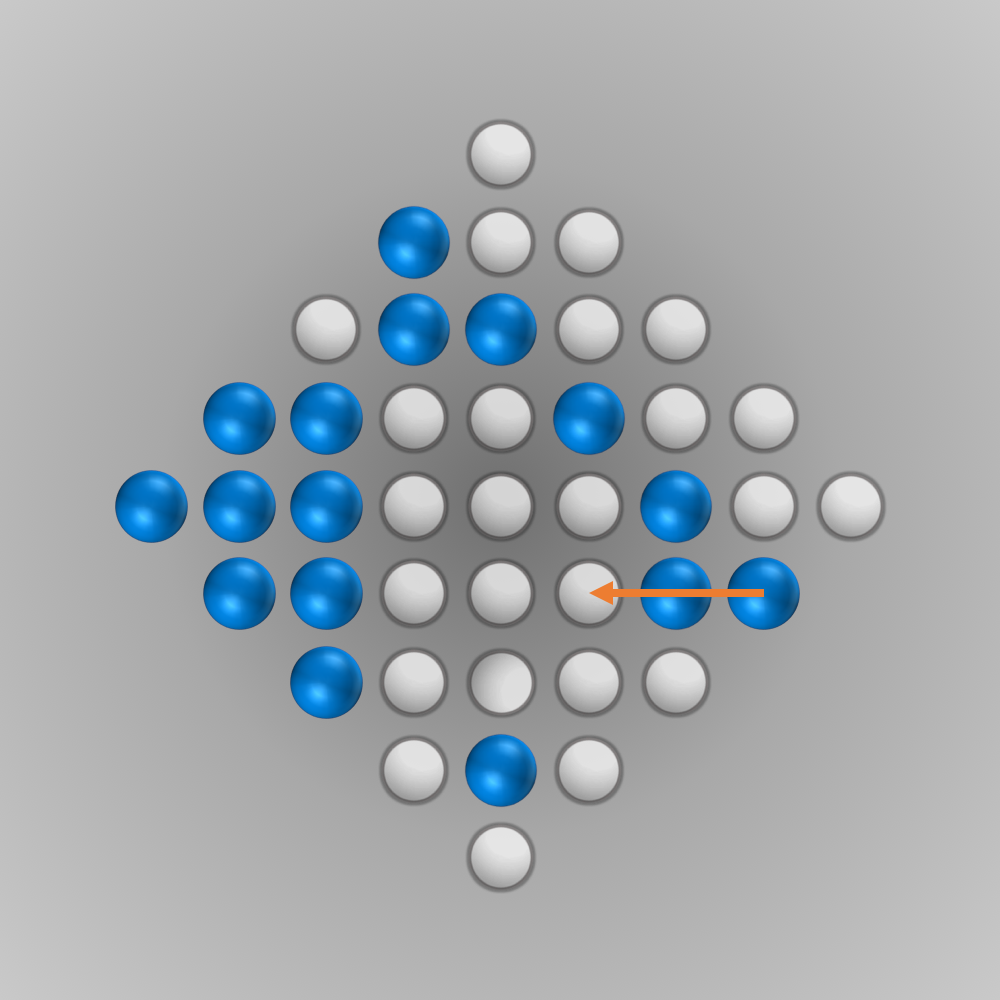

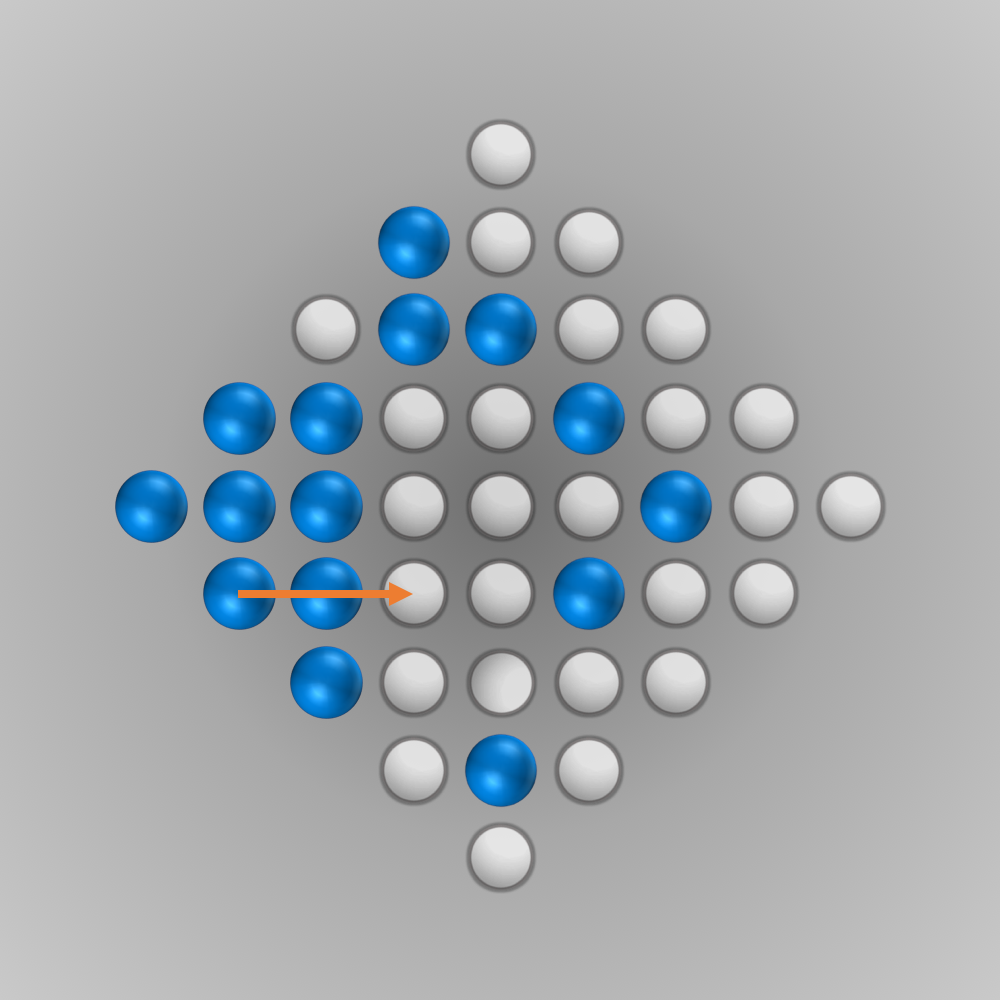

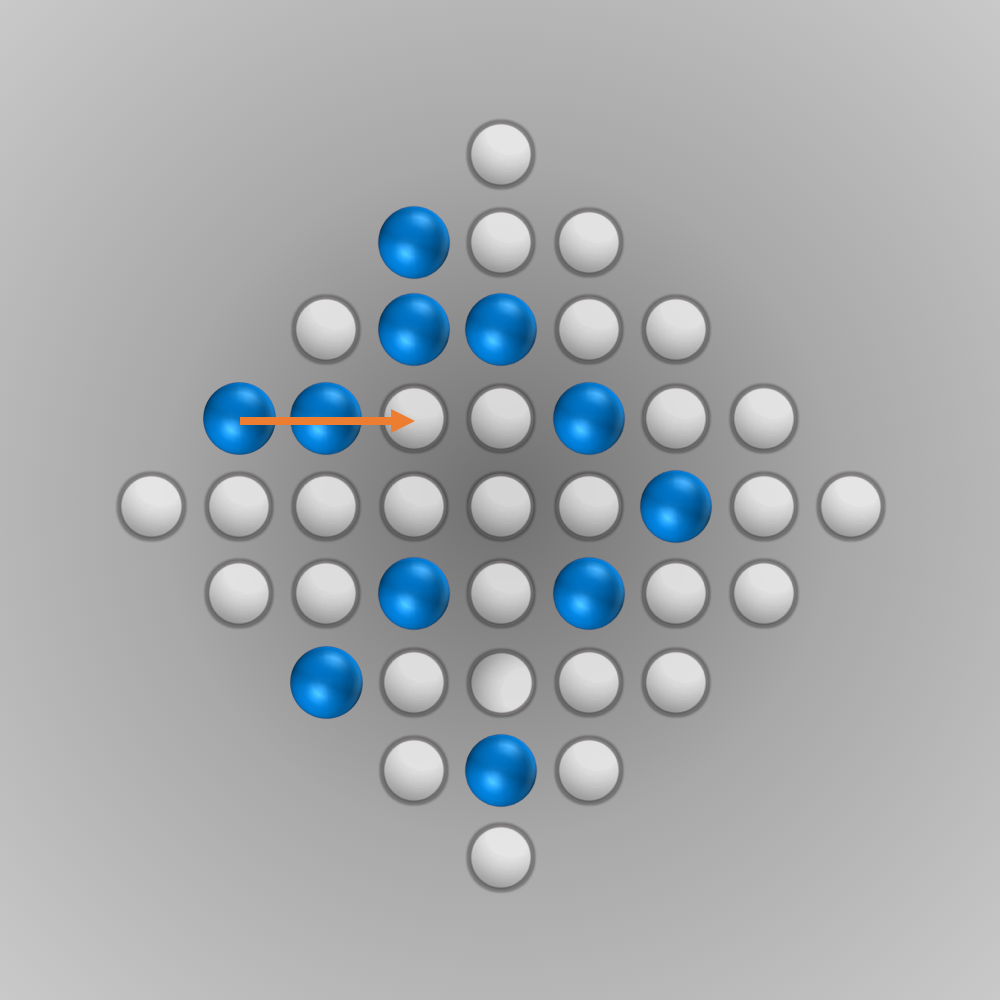

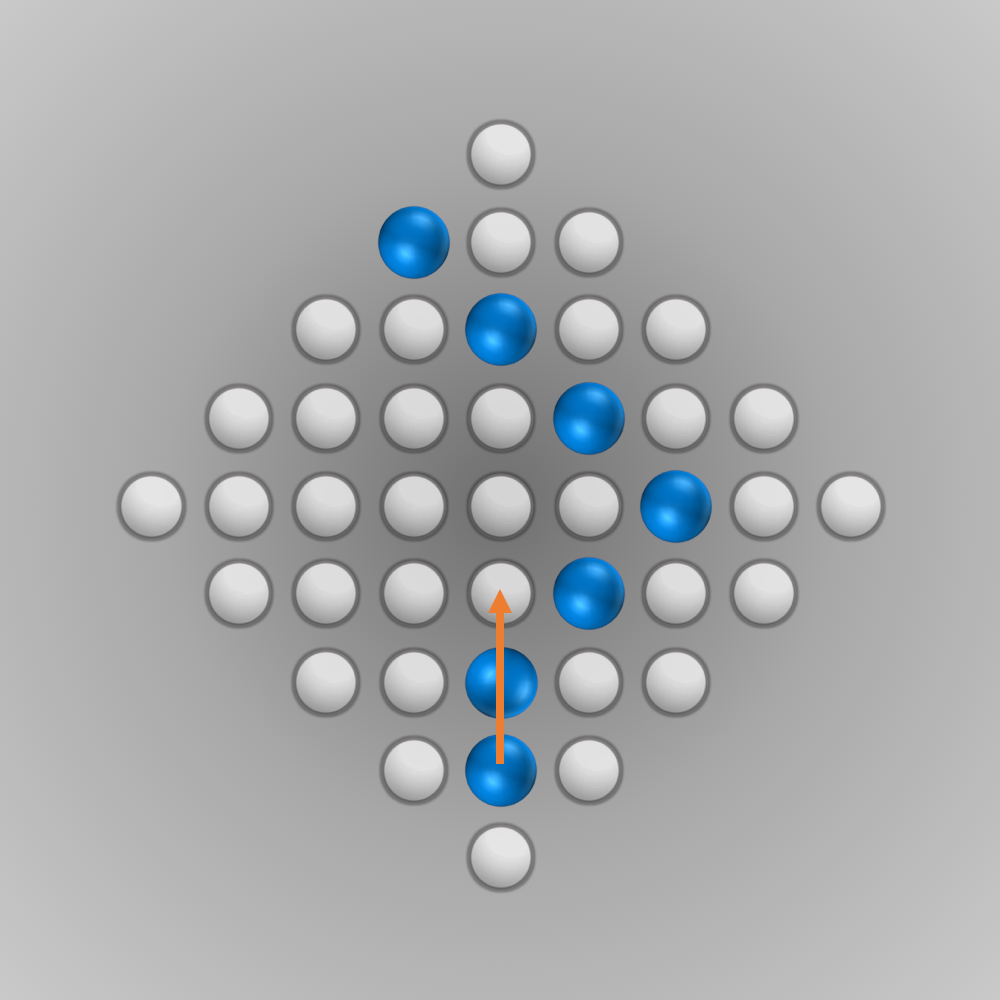

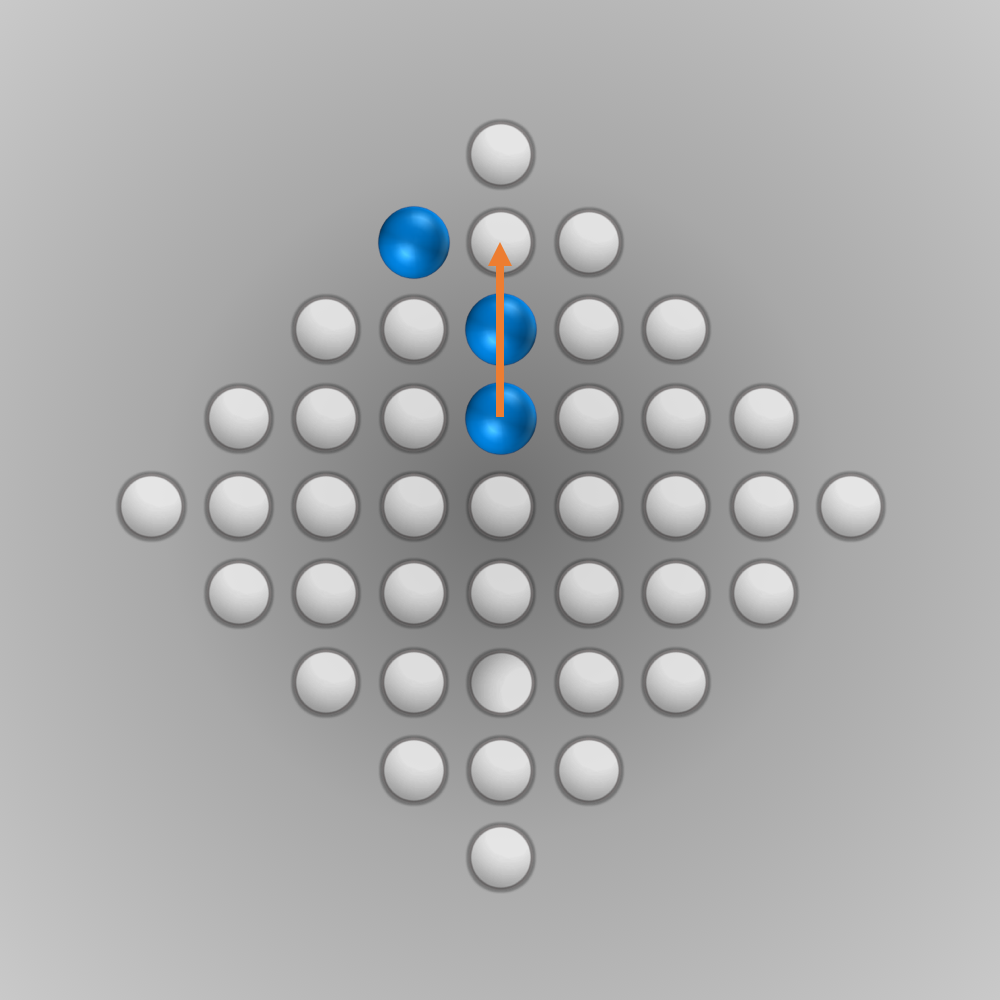

After we put all our components for the solver together, we can finally start running it (the whole source code is listed below). Initially, I ran the solver with a modified termination condition: solutions with \(n\) (e.g., \(n=5\)) left-over pegs in the final state were also accepted. A solver can find such a solution faster and be tested this way. After everything worked as intended, the solver was started for \(n=1\) (a solution is searched for where only one peg remains). Surprisingly, the solver found the solution much faster than expected: After about 6 minutes of computation, an optimal move sequence was found. This move sequence is shown in the slideshow below.

Source Code for Solving the Diamond-41 Peg Solitaire

The following code should be compile-able with most C compilers (gcc, etc.). When running the binary file, you will need some patience. The solver will require several minutes, up to one hour (depending on your machine and the size of the transposition table). Once the result is found, the program will list all moves and print the positions in reverse order.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

static const int TERM_CRITERION = 1;

// Specifying some constants

const uint64_t ZERO = 0x1p0 - 1;

const uint64_t B32 = 0x1p32 - 1;

const uint64_t B16 = 0x1p16 - 1;

const uint64_t B08 = 0x1p8 - 1;

const uint64_t B04 = 0x1p4 - 1;

const uint64_t B02 = 0x1p2 - 1;

const uint64_t B01 = 0x1p1 - 1;

uint64_t BORDER = 0x1p0 - 1;

uint64_t BOARD = 0x1p0 - 1;

// Contains bit-masks masking the lowest n bits

const uint64_t B_LVL[] = {B01, B02, B04, B08, B16, B32};

// Size of the board (number of holes

const int NUMBOARDBITS = 41;

// After initialization, this array will contain the bit-numbers of all holes starting

// from the top (left to right in the rows).

int BOARDBITS[NUMBOARDBITS] = {0};

// Number of bits that specify the border. Note that several bits are used as border

// on both sides of the board. This is due to the addressing scheme of the board and

// does not do any harm.

const int NUMBOUNDARYBITS = 15;

// The actual bits that specify the border of the board

const int BOUNDARYBITS[] = {5, 14, 23, 32, 41, 50, 39, 28, 17, 6, 59, 25, 36, 47, 58};

// Specifies the corners (edge) of the board. Required to prevent moves into the corners

// (or actually try them later)

const int NUMCORNERS = 16;

const int CORNERBITS[] = {4, 13, 22, 31, 40, 29, 18, 7, 60, 51, 42, 33, 24, 35, 46, 57};

// actual bit-mask for all the corner holes

uint64_t CORNERS = UINT64_C(0);

// How many rows (columns) does the board have

const int NUMROWS = 9;

// Operations for moving the pegs. An UP-operation will cause all pegs of the board to be

// moved up by one (some might be moved into the boundary).

static const int UP = 1;

static const int DOWN = -1;

static const int LEFT = -10;

static const int RIGHT = +10;

static const int DIRECTIONS[] = {DOWN, LEFT, UP, RIGHT};

// Constants for the transposition table. Using this table can significantly reduce the

// the efforts for the backtracking algorithm, since re-occuring positions do not have to

// be searched twice. Permutations of one move sequence might lead to the same position,

// which only has to be investigated once.

static const int HASHSIZE = (1 << 25);

static const int HASHMASK = HASHSIZE - 1;

static const int HASHMISS = -99;

// Number of symmetries. In total there are actually 8 symmetric positions for each board.

// Currently, only vertically and horizontally mirrored positions are considered. Rotations

// are not yet implemented.

static const int NUMSYMMETRIES = 4;

// Masks for horizontal and vertical lines. Needed for mirroring a board along the vertical or

// horizontal axis

static uint64_t HORLINES[NUMROWS] = {0};

static uint64_t VERTLINES[NUMROWS] = {0};

// Definition of one element of the transposition table. It contains a key (actual board, since several positions

// can be mapped to the same hash-table entry) and a value (number of remaining pegs when solving this specific

// position).

struct HashElement {

uint64_t key;

int value;

};

struct HashElement hashTable[HASHSIZE];

/*

* Modulo operator, since the %-operator is the remainder and cannot deal with negative integers

*/

int mod(int a, int b) {

int r = a % b;

return r < 0 ? r + b : r;

}

/*

* Determines the position of a single bit in a 64bit variable in logarithmic time.

*/

int bitPos(uint64_t x) {

int bPos = 0;

for (int i = 5; i >= 0; i--) {

if ((x & B_LVL[i]) == ZERO) {

int nBits = (int) B01 << i;

x >>= nBits;

bPos += nBits;

}

}

return bPos;

}

/*

* Fast way to count the one-bits in a 64-bit variable.

* Only requires as many iterations as bits are set.

*/

int bitCount(uint64_t x) {

int c = 0;

while (x != ZERO) {

x &= (x - UINT64_C(1));

c++;

}

return c;

}

/*

* Rotatate 64-bit variable x by y bits. Note that this is not a shift-operation but a real

* rotate-left

*/

static inline uint64_t rol(uint64_t x, unsigned int y) {

__asm__ ("rolq %1, %0" : "+g" (x) : "cJ" ((unsigned char) y));

return x;

}

/*

* Compute the bit indexes of the board from top to bottom (left to right in the rows) and from left to

* right (from top to bottom in each column)

*/

void initBOARDBits() {

int i, startRow = 4, startCol = 24, nrow = 1, j, k, l = 0, m;

// start with top cell and move line by line through

// the board (from left to right in each row).

for (i = 0; i < NUMROWS; i++) {

k = startRow;

m = startCol;

for (j = 0; j < nrow; j++, k = (k + 10) % 64, m--) {

BOARDBITS[l++] = k;

HORLINES[i] |= (UINT64_C(1) << k);

VERTLINES[i] |= (UINT64_C(1) << m);

}

nrow = (i < 4 ? nrow + 2 : nrow - 2);

// % operator is a remainder operator and not a modulo operator

startRow = mod((i < 4 ? startRow - 11 : startRow + 9), 64);

startCol = mod((i < 4 ? startCol + 11 : startCol + 9), 64);

}

}

/*

* Initialize the bit-masks that describe the boundary and the actual board.

*/

void initBoardnBoundary() {

for (int i = 0; i < NUMBOUNDARYBITS; i++)

BORDER |= (UINT64_C(1) << BOUNDARYBITS[i]);

for (int i = 0; i < NUMBOARDBITS; i++)

BOARD |= (UINT64_C(1) << BOARDBITS[i]);

}

/*

* Init the bit-mask representing all 16 corner holes of the board

*/

void initCorners() {

CORNERS = UINT64_C(0);

for (int i = 0; i < NUMCORNERS; i++) {

CORNERS |= (UINT64_C(1) << CORNERBITS[i]);

}

}

/*

* Initialize the transposition table

*/

void initHashTable() {

for (int i = 0; i < HASHSIZE; i++) {

hashTable[i].key = 0UL;

hashTable[i].value = 0;

}

}

void init() {

initBOARDBits();

initBoardnBoundary();

initHashTable();

initCorners();

}

/*

* Function to print the board to console

*/

void printBoard(uint64_t b) {

int l = 0, nrow = 1;

printf("\n");

for (int i = 0; i < NUMROWS; i++) {

for (int k = 0; k < NUMROWS - nrow; k++)

printf(" ");

printf("|");

for (int j = 0; j < nrow; j++) {

//char symb = 'o';

char symb = ((1UL << BOARDBITS[l++]) & b) != ZERO ? 'x' : 'o';

printf("%c|", symb);

}

printf("\n");

nrow = (i < 4 ? nrow + 2 : nrow - 2);

}

printf("\n");

}

/*

* Removes one peg from the board and returns the modified board

*/

uint64_t removePeg(uint64_t b, int bit) {

return b & (~(1UL << bit));

}

/*

* Place a peg at a certain position and return the modified board

*/

uint64_t setPeg(uint64_t b, int bit) {

return b | (1UL << bit);

}

/*

* Function to compute the hash for a 64bit variable. Maybe Zobrist keys would work better (has to be investigated

* in future).

*/

uint64_t getHash(uint64_t x) {

x = (x ^ (x >> 30)) * UINT64_C(0xbf58476d1ce4e5b9);

x = (x ^ (x >> 27)) * UINT64_C(0x94d049bb133111eb);

x = x ^ (x >> 31);

return x;

}

/*

* Mirror a board along the horizontal axis. This can be done quite fast.

*/

uint64_t mirrorHor(uint64_t b) {

uint64_t m = b & HORLINES[4];

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[0], 8 * DOWN); // First row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[1], 6 * DOWN); // Second row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[2], 4 * DOWN); // Third row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[3], 2 * DOWN); // Fourth row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[5], 2 * UP); // Sixth row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[6], 4 * UP); // Seventh row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[7], 6 * UP); // Eighth row

m |= rol(b & HORLINES[8], 8 * UP); // Ninth row

return m;

}

/*

* Mirror a board along the vertical axis. This can be done quite fast.

*/

uint64_t mirrorVert(uint64_t b) {

uint64_t m = b & VERTLINES[4];

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[0], 8 * RIGHT); // First Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[1], 6 * RIGHT); // Second Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[2], 4 * RIGHT); // Third Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[3], 2 * RIGHT); // Fourth Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[5], 2 * LEFT); // Sixth Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[6], 4 * LEFT); // Seventh Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[7], 6 * LEFT); // Eighth Column

m |= rol(b & VERTLINES[8], 8 * LEFT); // Ninth Column

return m;

}

/*

* Compute all mirrored positions for a board b and return all in the array m

*/

void mirror(uint64_t b, uint64_t m[]) {

m[0] = b;

m[1] = mirrorVert(b);

m[2] = mirrorHor(b);

m[3] = mirrorHor(m[1]);

}

/*

* Check if a position b or a mirrored equivalent is already stored in the transposition table. If yes, then

* return the value for this position.

*/

int getTransposition(uint64_t b) {

uint64_t m[NUMSYMMETRIES];

mirror(b, m);

for (int i = 0; i < NUMSYMMETRIES; i++) {

uint64_t hash = getHash(m[i]);

int hashIndex = ((int) hash & HASHMASK);

if (hashTable[hashIndex].key == m[i])

return hashTable[hashIndex].value;

}

return HASHMISS;

}

/*

* After a position is completely evaluated, store the value of the position in the transposition table

*/

void putTransposition(uint64_t b, int value) {

uint64_t hash = getHash(b);

int hashIndex = ((int) hash & HASHMASK);

hashTable[hashIndex].key = b;

hashTable[hashIndex].value = value;

}

/*

* Generates a list of possible moves in all directions for a board position b.

*

*/

void generateMoves(uint64_t b, uint64_t *const allmv) {// Generate all possible moves

int dir;

uint64_t mv;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

dir = DIRECTIONS[i];

mv = rol(rol(b, dir) & BOARD & b, dir) & BOARD & (~b);

uint64_t cmv = mv & CORNERS; // find all moves into corners

uint64_t zmv = mv & UINT64_C(1); // Move into the center is not good as well

// also some fields in each direction should be avoided first. These typically

// violate a so called Pagoda function

uint64_t dmv = UINT64_C(0);

if (dir == DOWN) {

dmv = mv & (UINT64_C(1) << 9 | UINT64_C(1) << 53 | UINT64_C(1) << 62);

} else if (dir == UP) {

dmv = mv & (UINT64_C(1) << 2 | UINT64_C(1) << 11 | UINT64_C(1) << 55);

} else if (dir == LEFT) {

dmv = mv & (UINT64_C(1) << 44 | UINT64_C(1) << 53 | UINT64_C(1) << 55);

} else if (dir == RIGHT) {

dmv = mv & (UINT64_C(1) << 9 | UINT64_C(1) << 11 | UINT64_C(1) << 20);

}

// Remove these moves from the initial move list and try them later,

// since they are likely sub-optimal

uint64_t mvLater = cmv | zmv | dmv;

mv ^= mvLater;

allmv[i] = mv;

allmv[i + 4] = mvLater;

}

}

int backtrack(uint64_t b);

/*

* Try all moves coded in mv (contains the destination holes) for a board b in a direction dir. Return, if a terminal

* position is reached.

*/

int tryMoves(uint64_t b, uint64_t mv, int dir) {

while (mv != ZERO) {

uint64_t x = ((mv - UINT64_C(1)) ^ mv) & mv;

// perform move

b |= x; // set peg at new position

b &= ~rol(x, -dir); // remove jumped-over peg

b &= ~rol(x, -2 * dir); // remove peg from old position

//recursion

int res = backtrack(b);

// undo move

b &= ~x; // remove peg from new position again

b |= rol(x, -dir); // add jumped-over peg again

b |= rol(x, -2 * dir); // set peg to old position

//printBoard(b);

mv &= (mv - 1); // remove this move from the list

if (res > 0 && res <= TERM_CRITERION) {

printf("Move: %d, %d", dir, bitPos(x));

printBoard(b);

return res;

}

}

return 0; // no solution found

}

/*

* Backtracking function to solve the board. It investigates all moves in the 4 possible directions. It randomly

* selects the first direction to enforce different searching order in case the solver is started several times.

* The possible moves for one position can be found very fast with only a dew bitwise operations.

*/

int backtrack(uint64_t b) {

// first check transposition table for this particular position

int value = getTransposition(b);

if (value != HASHMISS)

return value;

// will contain all possible moves later. Indexes 0-3 will contain the most promising moves in all 4 directions,

// and indexes 4-7 will contain the less promising moves in all directions

const int numTrys = 8;

uint64_t allmv[numTrys];

int dir;

// Find all possible moves, sorted according to some characteristics

generateMoves(b, allmv);

uint64_t mv;

int res, nomv = 0;

// Try all possible moves.

for (int i = 0; i < numTrys; i++) {

mv = allmv[i];

dir = DIRECTIONS[i & 3]; // = i % 4

if (mv != ZERO) {

res = tryMoves(b, mv, dir);

if (res > 0 && res <= TERM_CRITERION) {

// Not neccessary to put position in transposition table

return res;

}

} else // if no moves in specific direction is possible

nomv++;

}

int ret = 0;

if (nomv == numTrys) { // if no move in any direction was possible

ret = bitCount(b); // count number of pegs left

}

putTransposition(b, ret);

return ret; // no move could lead to a solution

}

/*

* Root-node of the solver. Initializes the board and all other necessary variables

* and then starts an exhaustive search.

*/

void solve() {

init();

// initial board

uint64_t b = BOARD;

b = removePeg(b, 57); // remove one peg

// Start back-tracking

backtrack(b);

}

int main() {

printf("Lets start solving the Diamond-41 peg solitaire problem...");

fflush(stdout);

time_t start, end;

double elapsed; // seconds

start = time(NULL);

solve();

end = time(NULL);

elapsed = difftime(end, start);

printf("Time in minutes: %f\n", elapsed / 60.0);

return 0;

}

/* ****/Source Code for Solving the English Peg Solitaire

Save the following code in a file solitaire-en.cpp and compile with g++ solitaire-en.cpp and then run the binary file. I wrote this code a long time ago, when I started learning programming. So, you will find many redundant code segments and strange programming styles. Nevertheless, the solver works and delivers exactly the solution which is shown in the above slideshow.

Interestingly, this naive implementation of the problem actually finds the solution very fast (on my computer in less than a second). Most likely, the solver has a good move order (just by chance) which leads to this fast solution. When changing the order of the moves, the solver can require several hours in order to find a correct solution.

solitaire-en.cpp

#include <fstream>

#include <iostream>

/*Output-Path for the generated moves*/

#define PATH "moves.txt"

/*

* Structure of the board. It has a dimension of 9 x 9, to also allow to put a border

* around the actual field.

*/

short int field[9][9];

/*

* Tracks the smallest number of pegs left on the board

*/

short int minimum = 99;

/*

* Keeps track of the current move sequence during the search

*/

short int move[31][3];

/*

* Initializes the board with proper values.

*/

void initialize(void);

/*

* The most important function of this program...

*/

void computation(short instance);

/*Counts the number of pegs on the board*/

short int CountStones(void);

/*Writes a found solution to a file*/

void WriteToFile(void);

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

initialize(); // Prepare everyting

std::cout << "The solution will be saved in moves.txt.";

computation(0); // Start exhaustive search

WriteToFile(); // Save solution

std::cout << "I found a solution....";

return 0;

}

void initialize(void) {

short int i, j;

for (i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

field[i][0] = 2; // Top boundary of the board

field[i][8] = 2; // Bottom boundary of the board

field[0][i] = 2; // Left boundary of the board

field[8][i] = 2; // Right boundary of the board

}

for (i = 1; i < 8; i++)

for (j = 1; j < 8; j++)

field[i][j] = 1;

/* Fill the corners of the board with twos, since they don't have holes.*/

/* Top left*/

field[1][1] = 2;

field[2][1] = 2;

field[1][2] = 2;

field[2][2] = 2;

/*To right*/

field[6][1] = 2;

field[7][1] = 2;

field[6][2] = 2;

field[7][2] = 2;

/*Bottom left*/

field[1][6] = 2;

field[2][6] = 2;

field[1][7] = 2;

field[2][7] = 2;

/*bottom right*/

field[6][6] = 2;

field[7][6] = 2;

field[6][7] = 2;

field[7][7] = 2;

/*The hole in the middle has to be empty*/

field[4][4] = 0;

}

/*Recursive function for backtracking

1. Find a peg

2. Find neighboring peg and check if there is a hole one further

3. Peg jumps over the other one into the hole. The peg has to be moved by 2 places and the other peg has to

be removed. */

void computation(short instance) {

short int i, j; // Loop variables

bool NoPossibilities = true; // This variable tracks, if a move could be performed or not from the current position

for (i = 1; i < 8; i++) // Start with 1, since 0 is the boundary

for (j = 1; j < 8; j++) // The same here...

{

if (field[j][i] == 1) // If there is a peg in this hole...

{

if (field[j + 1][i] == 1) // If there is another peg on the right...

{

if (field[j + 2][i] == 0) // and if one further there is an empty hole

{

NoPossibilities = false; // Set to false, since we have an option for a move

field[j][i] = 0; // Remove peg from its original position

field[j + 1][i] = 0; // Remove the peg over which we jump

field[j + 2][i] = 1; // Put first peg into new hole

move[instance][0] = j; // Save old x-position of peg

move[instance][1] = i; // Save old y-position of peg

move[instance][2] = 20; // Save direction of the move (20, for right)

computation(instance + 1); // recursion step

if (minimum == 1) // In case a solution was found, stop the search

break; // stop here...

field[j][i] = 1; // Undo move...

field[j + 1][i] = 1;

field[j + 2][i] = 0;

}

}

if (field[j - 1][i] == 1) // If there is another peg on the left...

{

/* almost same as above */

if (field[j - 2][i] == 0) {

NoPossibilities = false;

field[j][i] = 0;

field[j - 1][i] = 0;

field[j - 2][i] = 1;

move[instance][0] = j;

move[instance][1] = i;

move[instance][2] = -20;

computation(instance + 1);

if (minimum == 1)

break;

field[j][i] = 1;

field[j - 1][i] = 1;

field[j - 2][i] = 0;

}

}

if (field[j][i + 1] == 1) // If there is another peg below ...

{

/* almost same as above */

if (field[j][i + 2] == 0) {

NoPossibilities = false;

field[j][i] = 0;

field[j][i + 1] = 0;

field[j][i + 2] = 1;

move[instance][0] = j;

move[instance][1] = i;

move[instance][2] = 2;

computation(instance + 1);

if (minimum == 1)

break;

field[j][i] = 1;

field[j][i + 1] = 1;

field[j][i + 2] = 0;

}

}

if (field[j][i - 1] == 1) // If there is another peg above ...

{

/* almost same as above */

if (field[j][i - 2] == 0) {

NoPossibilities = false;

field[j][i] = 0;

field[j][i - 1] = 0;

field[j][i - 2] = 1;

move[instance][0] = j;

move[instance][1] = i;

move[instance][2] = -2;

computation(instance + 1);

if (minimum == 1)

break;

field[j][i] = 1;

field[j][i - 1] = 1;

field[j][i - 2] = 0;

}

}

}

}

if (NoPossibilities) // If no move could be performed...

{

short int count;

count = CountStones(); // Count remaining pegs

if (count == 1 && field[4][4] != 0) // In case only one peg is left in the center

minimum = count; // set minimum = 1, which stops the search

}

}

/*

* Counts the number of pegs on the board

*/

short int CountStones(void) {

short int i, j, count = 0;

for (i = 1; i < 8; i++) // Starts with 1, since 0 is the boarndary

for (j = 1; j < 8; j++) // same here....

{

if (field[i][j] == 1) // In case there is a peg at this position

count++; // increase counter

}

return count;

}

/*

* Write solution to file....

*/

void WriteToFile(void) {

std::ofstream file;

short int i, j;

file.open(PATH); // Create file specified above

file << "Explanation: Every move consists of three values.\n";

file << "1. X-Position of the peg\n";

file << "2. Y-Position of the peg\n";

file << "3. Direction, in which the selected peg jumps\n";

file << "(20->right, -20 left, 2 down, -2 up)\n\n";

for (i = 0; i < 31; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < 3; j++)

file << move[i][j] << '\n';

file << '\n';

}

file.close();

}Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: