Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: First Steps

This post is the 1st part of a series of 7 articles:

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: First Steps

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: Tree Search Algorithms

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: Board Representations

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: Move Ordering

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: Transposition Tables

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: Opening Databases

- Building Intelligent Agents for Connect-4: Final Considerations

The study of strategic board games is a long-standing and foundational area of research in artificial intelligence (AI). Over the years, countless approaches have been explored—often with very different goals and methodologies. Complex games such as chess, Go, and checkers have traditionally attracted significant attention due to their strategic depth and computational challenges.

In this blog post—and in future entries—we’ll turn our attention to Connect-4. While simpler than the aforementioned classics, Connect-4 still offers interesting AI challenges. We’ll explore various techniques for building strong-playing agents, ranging from handcrafted heuristics to learning-based and search-based methods.

More recently, I developed a high-performance C++ and Python version of a Connect-4 solver called BitBully, available here and here. Also, check out the related project page.

For those interested in a more educational or research-oriented setup, an earlier Java-based framework for Connect-4 is also available on GitHub: http://github.com/MarkusThill/Connect-Four.

Introduction

For decades, researchers have been fascinated by the question of whether machines can one day achieve a level of intelligence comparable to that of humans. This pursuit spans many fields, but one of the most established areas in artificial intelligence (AI) has been the development of intelligent programs capable of solving well-defined problems—strategic board games being a prime example.

The term artificial intelligence itself is difficult to pin down precisely, since even “intelligence” remains a debated and multifaceted concept. One influential definition comes from computer scientist John McCarthy, who described AI as:

“The science and engineering of making intelligent machines, especially intelligent computer programs. It is related to the similar task of using computers to understand human intelligence, but AI does not have to confine itself to methods that are biologically observable.”

Strategic board games have long played a central role in AI research. Over the past 70 years, a vast body of work has investigated the development of machine players, each with different objectives and methods. Early efforts focused particularly on chess, where programs evolved from simple evaluation functions to systems capable of defeating world champions.

A historical curiosity is the so-called Mechanical Turk, built in 1769 by Austrian-Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen. Claimed to be an automated chess-playing machine, it captivated audiences across Europe—until it was later revealed that a human operator was hidden inside. Much later, during World War II, Konrad Zuse designed the first known chess program using his own programming language Plankalkül.

Milestones like IBM’s Deep Blue defeating world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997 showcased the potential of brute-force search, leveraging custom hardware to evaluate over 2 million positions per second. Since then, AI research has moved toward even more sophisticated approaches, incorporating learning and generalization.

So why have board games become such a fertile ground for AI research?

Several properties make them especially appealing:

- Well-defined rules and goals: Most games have a fixed structure and a clearly defined win/loss condition. Unlike many real-world problems, the rules do not change mid-game.

- Discrete and fully observable environments: The current state of the game is fully known at all times, and transitions between states are (usually) deterministic.

- Manageable complexity with scalable difficulty: Despite their simplicity in terms of rules, many games have enormous state and action spaces, which demand clever search or learning strategies.

- Relevance to broader AI problems: Concepts such as planning, decision-making, adversarial search, and pattern recognition all play a role.

Humans excel at recognizing patterns, drawing analogies, and applying prior knowledge to new situations. For example, identifying familiar faces in photos or spotting tactical motifs in a chess position comes naturally to us. For machines, these tasks are far more difficult. Early AI systems in board games mostly relied on brute-force tree search and clever pruning. While effective, these systems lacked the ability to learn from experience in the human sense.

Machine learning methods, particularly Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Temporal Difference Learning (TDL), offer a different paradigm. In RL, an agent learns through interaction with its environment, receiving rewards based on outcomes. Over time, the agent develops a value function that helps evaluate positions and guide future decisions. Crucially, this process can allow the agent to improve its play autonomously—without relying on handcrafted rules or features.

However, even modern learning systems often depend on carefully chosen features to represent game states. Selecting and engineering these features is itself a creative challenge and can significantly impact performance.

In this blog series, we’ll begin by exploring classical tree search algorithms and heuristics before diving into more advanced, learning-based approaches to mastering board games—starting with Connect-4, a seemingly simple yet deeply strategic game.

Connect-4

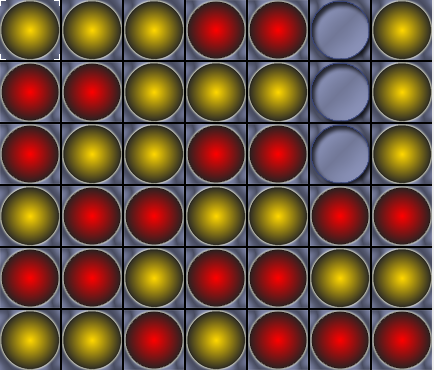

Connect-4 is a widely known two-player board game, typically played with the colors Yellow and Red, on a vertical grid consisting of seven columns and six rows. At the start of the game, the board is completely empty, offering 42 available positions.

One of the defining characteristics of Connect-4 is its vertical layout: players can only drop their discs into the top of a column. Due to gravity, a token always occupies the lowest unfilled row of the selected column. If a column is already filled with six tokens, no further moves can be made in that column, reducing the number of available options for both players.

Players alternate turns, starting with Yellow, aiming to create a line of four connected tokens of their own color. These four aligned discs may appear:

- Horizontally

- Vertically

- Diagonally (in either direction)

The first player to align four of their tokens in a row wins the game. If neither player manages to achieve this by the time all 42 cells are filled, the game ends in a draw.

Below is an example board position illustrating the game’s mechanics and strategic possibilities:

Although Connect-4 has a moderate state-space complexity of approximately

\(4.5 \cdot 10^{12}\) distinct positions (Edelkamp & Kissmann, 2008), and a game-tree complexity around

\(10^{21}\) (Allis, 1994), solving the game remains a non-trivial challenge even today.

The first known solution was independently discovered by Allen (Allen, 1989) and Allis (Allis, 1988) in 1988. They weakly solved the game, demonstrating that—assuming perfect play from both players—Yellow can always force a win if she starts by placing her first token in the center column. While Red cannot win under optimal play, she can delay defeat and force Yellow to use all available moves.

In 1994, Tromp (Bache & Lichman, 2013) went further and strongly solved the game for all positions with exactly 8 tokens, building a comprehensive endgame database that contains the game-theoretic values (win/loss/draw) of all non-trivial configurations.

Note: Tromp considered a position trivial if it contained an immediate win. While this is reasonable when Yellow has a direct winning move, it is debatable for Red: Red’s threats can often be neutralized by Yellow, allowing the game to proceed. Hence, the definition of triviality in this context is not entirely accurate.

Tromp’s computation evaluated all 67,557 relevant positions and took approximately 40,000 CPU hours—equivalent to about 4.5 years of computation time.

The table below shows the state-space complexity and leaf node counts for different numbers of plies. For instance, even with just 12 tokens placed (i.e., after 12 plies), the state-space complexity is still about

\(2.5 \cdot 10^5\) times smaller than that of the complete 42-token game

(final value from (Edelkamp & Kissmann, 2008)).

The source code used to generate the table is available in the appendix and on GitHub (Python or Java).

| Plies | Leaf Nodes | State-Space Complexity |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 7 | 8 |

| 2 | 49 | 57 |

| 3 | 238 | 295 |

| 4 | 1,120 | 1,415 |

| 5 | 4,263 | 5,678 |

| 6 | 16,422 | 22,100 |

| 7 | 53,955 | 76,055 |

| 8 | 181,597 | 257,652 |

| 9 | 534,085 | 791,737 |

| 10 | 1,602,480 | 2,394,217 |

| 11 | 4,231,877 | 6,626,094 |

| 12 | 11,477,673 | 18,102,767 |

| \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) |

| 42 | ? | \(4,531,985,219,092 \approx 4.5 \times 10^{12}\) |

You can also find the list with up to 26 plies on OEIS.

A Connect-4 Agent Based on Tree-Search Techniques

Summary of the Upcoming Blog Posts

Some time ago, I developed a perfect-playing Connect-4 agent. The project began with a simple Minimax agent—a classic tree-search algorithm—and was gradually refined with a series of optimizations. The final version integrates advanced search techniques and is supported by comprehensive databases to master the game’s opening phase.

For Connect-4, we benefit from Tromp’s 8-ply opening database, which I further extended to include all 8-ply positions with immediate threats for Yellow, as these were originally omitted. Additionally, I generated a Huffman-encoded endgame database covering all positions with exactly 12 tokens, storing both the expected outcome and the precise number of moves remaining until the end of the game (under perfect play).

The core Minimax search is enhanced with several techniques:

- Alpha-Beta Pruning

- Move Ordering

- Symmetry Exploitation

- Zobrist Hashing

- Two-Stage Transposition Tables to detect repeated positions from different move orders

- Enhanced Transposition Cutoffs (ETC)

Bitboards for Fast and Efficient Board Representation

The agent uses bitboards as the main data structure for board representation. In this scheme, each Connect-4 cell is encoded using two bitfields, one per player, requiring a total of

\(2 \times 42 = 84\) bits to represent a position. With a well-chosen layout of cells in memory, common operations become extremely efficient thanks to native CPU support for bitwise instructions (e.g., AND, OR, XOR, bit shifts).

Typical board operations—such as placing/removing tokens, mirroring, rotation, copying, and detecting terminal states—can be performed significantly faster with bitboards than with traditional structures like 2D arrays.

In particular, terminal state detection (i.e., checking for 4-in-a-row) is a time-critical task in Connect-4. With bitboards, a highly optimized solution exists that vastly outperforms conventional implementations. Moreover, bitboards are memory-efficient, which is crucial when storing millions of positions in transposition tables.

Performance Highlights

Thanks to all these optimizations, the agent ranks among the fastest perfect-playing Connect-4 solvers:

- On a vintage Pentium-4 machine, it can solve the empty board in under 4 minutes, without using any opening database and with just 24 MB of transposition table memory.

- In the typical configuration—using a 12-ply opening database and the same 24 MB transposition table—most positions can be solved in a fraction of a second.

These techniques will be explored in greater detail in the upcoming blog posts.

-

BitBully: A High-Speed Connect-4 Solver

BitBully is a blazing-fast, perfect-playing Connect-4 solver written in C++ with seamless Python bindings. Designed for both developers and researchers, it offers a powerful toolkit for analyzing game-theoretic strategies and solving arbitrary board positions with high efficiency.

Key features include:

- Bitboard Engine using low-level bitwise operations

- MTD(f) and null-window search for fast perfect-play solving

- Opening database covering all positions up to 12 discs

- Advanced heuristics: threat detection, transposition tables, move ordering

- Cross-platform (Linux, Windows, macOS) with zero-setup Python wheels

- Open Source under the AGPL-3.0 license

Available here:

👉 GitHub · PyPI · DocsAlso, check out the related project page.

-

Connect-4 Java Framework

A comprehensive software framework for Connect-4 implemented in Java is available on GitHub. It provides a flexible environment for conducting learning experiments and evaluating different AI strategies.

The framework includes a graphical user interface (GUI) that offers:

- Visual inspection of the game state and progress

- Tools for performance evaluation and analysis

- Import/export functionalities for game positions and statistics

- Interactive play between the user and various agents, including:

- Random agents

- Temporal-Difference Learning (TDL) agents

- Minimax search agents

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) agents

- And more

The framework is open-source and can be downloaded from:

👉 github.com/MarkusThill/Connect-Four

References

- Symbolic classification of general two-player gamesIn KI 2008: Advances in Artificial Intelligence, 2008

- Searching for Solutions in Games and Artificial IntelligenceUniversity of Limburg, 1994

- A Note on the Computer Solution of Connect-4In Heuristic Programming in AI 1: The First Computer Olympiad, 1989

- A knowledge-based approach of Connect-4. The game is solved: White winsDepartment of Mathematics and Computer Science, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988

- UCI Machine Learning Repository. Tromp’s 8-ply database2013

Counting Positions on the Connect-4 Board with 12 and less Plies

-

from bitbully import bitbully_core as bbc b = bbc.Board() # empty board board_list_3ply = b.allPositions(3, True) # All positions with exactly 3 tokens len(board_list_3ply) # should be 238 according to https://oeis.org/A212693 -

package miscellaneous; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.HashSet; import c4.ConnectFour; /** * * Always do 3 runs for counting the positions. First, count all positions * with a yellow stone in the left-bottom-corner, then with a red stone, and * last run when left-bottom-corner is empty. This is done, because the Hashset * can be reset after each run, and doesn't need that much memory. * * @author Markus Thill * */ public class CountPositionsC4 extends ConnectFour { private int maxDepth = 6; private boolean countAll = false; private long count = 0; HashSet<LongArr> hs = new HashSet<LongArr>(16777216); private static final long MASK = 0x20000000000L; int run = 0; private void tree(int depth, int player) { if (depth == maxDepth || countAll) { boolean putElement = false; switch (run) { case 0: // yellow stone in bottom-left corner putElement = (fieldP1 & MASK) == MASK; break; case 1: // red stone in bottom-left corner putElement = (fieldP2 & MASK) == MASK; break; case 2: // no stone in bottom-left corner putElement = ((fieldP1 | fieldP2) & MASK) == 0x0L; break; } if (putElement) { LongArr key = new LongArr(fieldP1, fieldP2); if (hs.add(key)) { count++; if ((count & 0xFFFFL) == 0xFFFFL) { System.out.println("Count until now: " + count); System.gc(); } } } if (depth == maxDepth) return; } int moves[] = generateMoves(player, true); for (int i = 0; moves[i] != -1; i++) { if (canWin(moves[i])) return; putPiece(player, moves[i]); tree(depth + 1, player == PLAYER1 ? PLAYER2 : PLAYER1); removePiece(player, moves[i]); } } /** * @param toPly * number of plys, for which number positions are calculated * @param countAll * count all positions, not only leaf-nodes */ public void countPositions(int toPly, boolean countAll) { resetBoard(); hs.clear(); maxDepth = toPly; count = 0; this.countAll = countAll; for (run = 0; run < 3; run++) { resetBoard(); hs.clear(); maxDepth = toPly; tree(0, PLAYER1); } if (!countAll) System.out.println("Number of different positions for exactly " + maxDepth + " stones: " + count + ""); else System.out.println("Number of different positions with 0 to " + maxDepth + " stones: " + count + ""); } /** * @param plyRange * number of plys (range), for which number positions are * calculated * @param countAll * count all positions, not only leaf-nodes */ public void countPositions(int[] plyRange, boolean countAll) { for (int i = plyRange[0]; i <= plyRange[1]; i++) countPositions(i, countAll); } private class LongArr { private long arr[]; LongArr(long val1, long val2) { arr = new long[] { val1, val2 }; } public int hashCode() { return Arrays.hashCode(arr); } public boolean equals(Object obj) { LongArr o = (LongArr) obj; return Arrays.equals(arr, o.arr); } } public static void main(String[] args) { CountPositionsC4 cp = new CountPositionsC4(); cp.countPositions(0, false); // cp.countPositions(new int[]{0,9},false); } }

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: