The Relationship between the Mahalanobis Distance and the Chi-Squared Distribution

\( \renewcommand{\vec}[1]{\boldsymbol{\mathbf{#1}}} \def\matr#1{\boldsymbol{\mathbf{#1}}} \def\tp{\mathsf T} \DeclareMathOperator{\E}{\mathbb{E}} \)

Gaussian distributions are a common choice for anomaly detection, especially when the data is roughly normally distributed. The parameters of the distribution can be estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which gives the sample mean and covariance matrix. Once these parameters are known, the next step is to decide on a threshold that separates normal data from anomalies. A simple approach is to set this threshold based on the probability density function (PDF): if a new data point has a PDF value below the threshold, it is flagged as anomalous.

In one dimension, this threshold separates the tails of the distribution from its center. In two dimensions, the boundary takes the shape of an ellipse, and in higher dimensions, it becomes an ellipsoid. All points on such a boundary are equally distant from the mean in terms of the Mahalanobis distance, which makes this distance a useful alternative for defining thresholds.

Unlike the PDF, the Mahalanobis distance does not rely on assuming a Gaussian distribution. Still, if the data is approximately Gaussian, the squared Mahalanobis distance follows a Chi-square distribution—a relationship that can also be confirmed visually using a quantile–quantile plot.

Prerequisites

Matrix Algebra

The product of an $n \times \ell$ matrix $\matr A$ and an $\ell \times p$ matrix $\matr B$ is defined entry-wise as

\[(\matr A \matr B)_{ij} = \sum_{k=1}^\ell \matr A_{ik}\,\matr B_{kj}.\]In particular, the product of a matrix $\matr A$ with its transpose $\matr A^\top$ can be written as

\[\begin{align} (\matr A \matr A^\top)_{ij} &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell \matr A_{ik}\,\matr A^\top_{kj} = \sum_{k=1}^\ell \matr A_{ik}\,\matr A_{jk}, \nonumber \\[6pt] \matr A \matr A^\top &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell \vec a_{k}\,\vec a_{k}^\top, \label{eq:matrixProductWithTranspose} \end{align}\]where $\vec a_{k}$ denotes the $k$-th column vector of $\matr A$.

We will also use the following simple relation for vectors $\vec a, \vec b$:

\[\begin{align} x &= \vec a^\top \vec b, \\ y &= \vec b^\top \vec a = x^\top = x, \\ xy &= \vec a^\top \vec b \,\vec b^\top \vec a = x^2 = (\vec a^\top \vec b)^2. \label{eq:multOfTwoScalars} \end{align}\](Inverse of a Matrix Product)

For invertible square matrices $ \matr A \in \mathbb R^{n \times n} $ and $ \matr B \in \mathbb R^{n \times n} $, the inverse of their product is

\[\begin{align} (\matr A \matr B)^{-1} &= \matr B^{-1} \matr A^{-1}. \label{eq:inverseProduct} \end{align}\]Indeed,

\[\begin{align} (\matr A \matr B)(\matr B^{-1} \matr A^{-1}) &= \matr A(\matr B \matr B^{-1}) \matr A^{-1} \\[4pt] &= \matr A \mathbf I \matr A^{-1} \\[4pt] &= \matr A \matr A^{-1} \\[4pt] &= \mathbf I, \end{align}\]which verifies the result.

Note that the order of the factors is crucial: in general $ \matr B^{-1} \matr A^{-1} \ne \matr A^{-1} \matr B^{-1} $, since matrix multiplication is not commutative.

Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

For a square $n \times n$ matrix $\matr A$, a non-zero vector $\vec u$ is called an eigenvector of $\matr A$ if it satisfies

\[\matr A \vec u = \lambda \vec u,\]where the scalar $\lambda$ is the corresponding eigenvalue.

If the eigenvectors of $\matr A$ are collected as the columns of a matrix $\matr U \in \mathbb R^{n \times n}$, with the $i$-th column given by $\vec u^{(i)}$, and if $\matr \Lambda$ is the diagonal matrix containing the associated eigenvalues $\lambda_i$, then

\[\begin{align} \matr A \matr U &= \matr U \matr \Lambda, \nonumber \\[6pt] \matr A &= \matr U \matr \Lambda \matr U^{-1}, \label{eq:eigendecomp} \end{align}\]which is known as the eigenvalue decomposition of $\matr A$.

If $\matr A$ is symmetric, its eigenvectors are orthogonal (and can be chosen to be orthonormal). In that case, $\matr U$ is an orthogonal matrix, so $\matr U^{-1} = \matr U^\top$, and the decomposition simplifies to

\[\matr A = \matr U \matr \Lambda \matr U^\top.\]The square root of a matrix $\matr A$ (denoted $\matr A^{\tfrac{1}{2}}$), defined such that $\matr A^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \matr A^{\tfrac{1}{2}} = \matr A$, can be expressed using the eigenvalue decomposition as:

\[\begin{align} \matr A^{\tfrac{1}{2}} &= \matr U \matr \Lambda^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \matr U^{\tp}, \label{eq:sqrtSymMatrix} \end{align}\]where $\matr \Lambda^{\tfrac{1}{2}}$ is the diagonal matrix containing the square roots of the eigenvalues of $\matr A$.

Verifying this:

\[\begin{align*} \matr A^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \cdot \matr A^{\tfrac{1}{2}} &= \matr U \matr \Lambda^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \matr U^{\tp} \matr U \matr \Lambda^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \matr U^{\tp} \\ &= \matr U \matr \Lambda^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \matr I \matr \Lambda^{\tfrac{1}{2}} \matr U^{\tp} \\ &= \matr U \matr \Lambda \matr U^{\tp} \\ &= \matr A. \end{align*}\]Similarly, the inverse of $\matr A$ can be expressed through its eigenvalue decomposition. Using the associativity of matrix multiplication, we obtain:

\[\begin{align} \matr A^{-1} &= \big( \matr U \matr \Lambda \matr U^{-1} \big)^{-1} \\ &= \big( \matr U^{-1} \big)^{-1} \matr \Lambda^{-1} \matr U^{-1} \\ &= \matr U \matr \Lambda^{-1} \matr U^{-1} \nonumber \\ &= \matr U \matr \Lambda^{-1} \matr U^{\tp}, \label{eq:eigenvalueInverse} \end{align}\]where $\matr \Lambda^{-1}$ is a diagonal matrix containing the reciprocals of the eigenvalues of $\matr A$.

Note that $\matr \Lambda^{-1}$ is again a diagonal matrix containing the reciprocal eigenvalues of $\matr A$.

Linear Affine Transform of a Normally Distributed Random Variable

Consider a random variable $X \sim \mathcal N(\vec \mu_x, \matr \Sigma_x)$ with mean vector $\vec \mu_x$ and covariance matrix $\matr \Sigma_x$.

Applying a linear affine transformation with matrix $\matr A$ and vector $\vec b$ yields a new random variable $Y$:

The mean $\vec \mu_y$ and covariance $\matr \Sigma_y$ of $Y$ can be derived as follows:

\[\begin{align} \vec \mu_y &= \E \{ Y \} \\ &= \E \{ \matr A X + \vec b \} \\ &= \matr A \E \{ X \} + \vec b \\ &= \matr A \vec \mu_x + \vec b, \label{eq:AffineLinearTransformMean} \end{align}\]and

\[\begin{align} \matr \Sigma_y &= \E \{ (Y - \vec \mu_y)(Y - \vec \mu_y)^\tp \} \\ &= \E \{ \big[ \matr A (X - \vec \mu_x) \big] \big[ \matr A (X - \vec \mu_x) \big]^\tp \} \\ &= \E \{ \matr A (X - \vec \mu_x)(X - \vec \mu_x)^\tp \matr A^\tp \} \\ &= \matr A \E \{ (X - \vec \mu_x)(X - \vec \mu_x)^\tp \} \matr A^\tp \\ &= \matr A \matr \Sigma_x \matr A^\tp. \label{eq:AffineLinearTransformCovariance} \end{align}\]Thus, affine transformations preserve Gaussianity: the result is still normally distributed, but with a mean shifted and scaled by $\matr A$ and $\vec b$, and a covariance matrix transformed as $\matr A \matr \Sigma_x \matr A^\tp$.

Quantile Estimation for Multivariate Gaussian Distributions

Estimating quantiles for multivariate Gaussian distributions is more involved than in the one-dimensional case. In one dimension, quantiles can be obtained by directly evaluating the cumulative distribution function in the tails of the distribution. In higher dimensions, however, this approach does not generalize in a straightforward way.

In the bivariate case, quantiles can be visualized as ellipses, and in higher dimensions as ellipsoids. A useful tool for describing such contours is the Mahalanobis distance, which measures the distance of a point from the mean while accounting for the covariance structure of the distribution. All points at the same Mahalanobis distance from the mean lie on the surface of an ellipsoid.

More formally, the usual definition of a $p$-quantile involves a random variable: the $p$-quantile of a distribution is the value $q_p$ such that the probability of the random variable being less than or equal to $q_p$ is exactly $p$. For a multivariate Gaussian distribution, we can treat the squared Mahalanobis distance between a random point $\vec x$ and the mean $\vec \mu$ as such a random variable:

\[d^2 = (\vec x - \vec \mu)^\tp \matr \Sigma^{-1} (\vec x - \vec \mu).\]The $p$-quantile then corresponds to the threshold value $q_p$ such that

\[P(d^2 \leq q_p) = p.\]Geometrically, the set of all points with $d^2 \leq q_p$ forms an ellipsoid centered at the mean.

A naive way to compute these quantiles is through a Monte Carlo approach: sample many points from the multivariate Gaussian distribution, compute their Mahalanobis distances, and then estimate the quantile empirically. While straightforward, this method becomes computationally inefficient, especially if quantiles need to be evaluated repeatedly.

Fortunately, there is a more direct connection: the squared Mahalanobis distance of a Gaussian-distributed random vector follows a Chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the dimensionality $k$ of the Gaussian. This means that the $p$-quantile can be computed directly as

\[q_p = \chi^2_{k,p},\]where $\chi^2_{k,p}$ is the $p$-quantile of the Chi-square distribution with $k$ degrees of freedom. In other words, for a $k$-dimensional Gaussian, the region

\[\{ \vec x \in \mathbb R^k : d^2 \leq \chi^2_{k,p} \}\]defines the ellipsoidal contour that contains probability mass $p$.

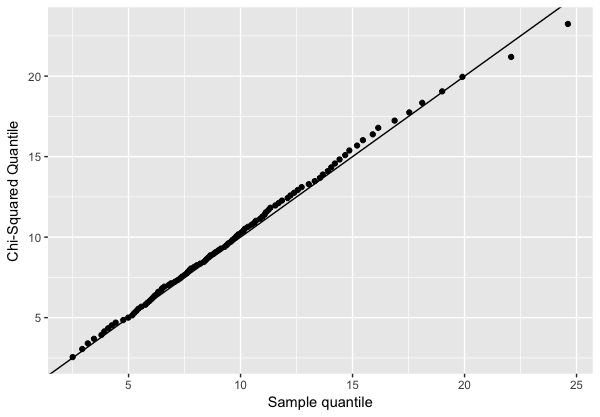

Empirical Evidence that the Mahalanobis Distance is Chi-Square Distributed

The relationship between the Mahalanobis distance and the Chi-square distribution can also be verified empirically.

A common tool for this is the Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plot, which compares the quantiles of two distributions.

If the squared Mahalanobis distance of samples drawn from a Gaussian distribution truly follows a Chi-square distribution, then the Q-Q plot of their quantiles should lie approximately on the identity line.

The following R script demonstrates this approach by generating a sample from a multivariate Gaussian distribution, computing the squared Mahalanobis distances, and comparing them against the theoretical Chi-square quantiles:

library(Matrix)

library(MASS)

library(ggplot2)

DIM = 10

nSample = 1000

Posdef <- function (n, ev = runif(n, 0, 1))

{

Z <- matrix(ncol=n, rnorm(n^2))

decomp <- qr(Z)

Q <- qr.Q(decomp)

R <- qr.R(decomp)

d <- diag(R)

ph <- d / abs(d)

O <- Q %*% diag(ph)

Z <- t(O) %*% diag(ev) %*% O

return(Z)

}

Sigma = Posdef(DIM)

muhat = rnorm(DIM)

sample <- mvrnorm(n=nSample, mu = muhat, Sigma = Sigma)

C <- .5*log(det(2*pi*Sigma))

mahaDist2 <- mahalanobis(x=sample, center=muhat,cov=Sigma)

#

# Interestingly, the Mahalanobis distance of samples follows a Chi-Square distribution

# with d degrees of freedom

#

pps <- (1:100)/(100+1)

qq1 <- sapply(X = pps, FUN = function(x) {quantile(mahaDist2, probs = x) })

qq2 <- sapply(X = pps, FUN = qchisq, df=ncol(Sigma))

dat <- data.frame(qEmp= qq1, qChiSq=qq2)

p <- ggplot(data = dat) + geom_point(aes(x=qEmp, y=qChiSq)) +

xlab("Sample quantile") +

ylab("Chi-Squared Quantile") +

geom_abline(slope=1)

plot(p)

The Squared Mahalanobis Distance follows a Chi-Square Distribution

In this section we prove the conjecture: “The squared Mahalanobis distance of a Gaussian-distributed random vector $\matr X$ and the center $\vec\mu$ of this Gaussian distribution follows a Chi-square distribution.”

Derivation Based on the Eigenvalue Decomposition

The Mahalanobis distance between two points $\vec x$ and $\vec y$ is defined as

\[\begin{align} d(\vec x,\vec y) = \sqrt{(\vec x -\vec y )^\tp \matr \Sigma^{-1} (\vec x - \vec y)}. \end{align}\]Thus, the squared Mahalanobis distance of a random vector $\matr X$ and the center $\vec \mu$ of a multivariate Gaussian distribution is defined as:

\[\begin{align} D = d(\matr X,\vec \mu)^2 = (\matr X -\vec \mu )^\tp \matr \Sigma^{-1} (\matr X - \vec \mu ), \label{eq:sqMahalanobis} \end{align}\]where $\matr \Sigma$ is a $\ell \times \ell$ covariance matrix and $\vec \mu \in \mathbb{R}^\ell$ is the mean vector. In order to achieve a different representation of $D$ one can first perform an eigenvalue decomposition on $\matr \Sigma^{-1}$ which is (with Eq. $\eqref{eq:eigenvalueInverse}$ and assuming orthonormal eigenvectors):

\[\begin{align} \matr \Sigma^{-1} &= \matr U \matr \Lambda^{-1} \matr U^{-1} = \matr U \matr \Lambda^{-1} \matr U^{T} \end{align}\]With Eq. \eqref{eq:matrixProductWithTranspose} we obtain:

\[\begin{align} \matr \Sigma^{-1} &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell \lambda_k^{-1} \vec u_{k} \vec u_{k}^\tp \label{eq:SigmaInverseAsSum} \end{align}\]where $\vec u_{k}$ is the $k$-th eigenvector of the corresponding eigenvalue $\lambda_k$. Plugging \eqref{eq:SigmaInverseAsSum} back into \eqref{eq:sqMahalanobis} results in:

\[\begin{align*} D &= (\matr X -\vec \mu )^\tp \matr \Sigma^{-1} (\matr X - \vec \mu ) = (\matr X -\vec \mu )^\tp \Bigg( \sum_{k=1}^\ell \lambda_k^{-1} \vec u_{k} \vec u_{k}^\tp \Bigg) (\matr X - \vec \mu ) \\ &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell \lambda_k^{-1} (\matr X -\vec \mu )^\tp \vec u_{k} \vec u_{k}^\tp (\matr X - \vec \mu )\\ &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell \lambda_k^{-1} \Big[ \vec u_{k}^\tp (\matr X - \vec \mu ) \Big]^2 = \sum_{k=1}^\ell \Big[ \lambda_k^{-\frac{1}{2}} \vec u_{k}^\tp (\matr X - \vec \mu ) \Big]^2\\ &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell Y_k^2 \end{align*}\]where $Y_k$ is a new random variable based on an affine linear transform of the random vector $\matr X$. According to Eq. \eqref{eq:AffineLinearTransformMean} , we have $\matr Z = (\matr X - \vec \mu ) \thicksim N(\vec 0,\Sigma)$. If we set $ \vec a_{k}^\tp = \lambda_k^{-\frac{1}{2}} \vec u_{k}^\tp$ then we get $Y_k = \vec a_{k}^\tp \matr Z = \lambda_k^{-\frac{1}{2}} \vec u_{k}^\tp \matr Z$. Note that $Y_k$ is now a random variable drawn from a univariate normal distribution $Y_k \thicksim N(0,\sigma_k^2)$, where, according to \eqref{eq:AffineLinearTransformCovariance}:

\[\begin{align} \sigma_k^2 &= \vec a_{k}^\tp \Sigma \vec a_{k}= \lambda_k^{-\frac{1}{2}} \vec u_{k}^\tp \Sigma \lambda_k^{-\frac{1}{2}} \vec u_{k} \\ &= \lambda_k^{-1} \vec u_{k}^\tp \Sigma \vec u_{k} \label{eq:smallSigma} \end{align}\]If we insert $\matr \Sigma = \sum_{j=1}^\ell \lambda_j \vec u_{j} \vec u_{j}^\tp$ into Eq. \eqref{eq:smallSigma}, we get:

\[\begin{align*} \sigma_k^2 &= \lambda_k^{-1} \vec u_{k}^\tp \Sigma \vec u_{k} = \lambda_k^{-1} \vec u_{k}^\tp \Bigg( \sum_{j=1}^\ell \lambda_j \vec u_{j} \vec u_{j}^\tp \Bigg) \vec u_{k} = \sum_{j=1}^\ell \lambda_k^{-1} \vec u_{k}^\tp \lambda_j \vec u_{j} \vec u_{j}^\tp \vec u_{k} \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^\ell \lambda_k^{-1} \lambda_j \vec u_{k}^\tp \vec u_{j} \vec u_{j}^\tp \vec u_{k} \end{align*}\]Since all eigenvectors $\vec u_{i}$ are pairwise orthonormal the dotted products $\vec u_{k}^\tp \vec u_{j}$ and $\vec u_{j}^\tp \vec u_{k}$ will be zero for $j \neq k$. Only for the case $j = k$ we get:

\[\begin{align*} \sigma_k^2 &= \lambda_k^{-1} \lambda_k \vec u_{k}^\tp \vec u_{k} \vec u_{k}^\tp \vec u_{k} = \lambda_k^{-1} \lambda_k ||\vec u_{k}||^2 ||\vec u_{k}||^2 = \lambda_k^{-1} \lambda_k ||\vec u_{k}||^2 ||\vec u_{k}||^2 \\ &= 1, \end{align*}\]since the the norm $||\vec u_{k}||$ of a orthonormal eigenvector is equal to 1. Thus, the squared Mahalanobis distance can be expressed as:

\[\begin{align*} D = \sum_{k=1}^\ell Y_k^2, \end{align*}\]where

\[\begin{align} Y_k \thicksim N(0,1). \end{align}\]Now the Chi-square distribution with $\ell$ degrees of freedom is exactly defined as being the distribution of a variable which is the sum of the squares of $\ell$ random variables being standard normally distributed. Hence, $D$ is Chi-square distributed with $\ell$ degrees of freedom.

Alternative Derivation Based on the Whitening Property of the Mahalanobis Distance

Since the inverse $\matr \Sigma^{-1}$ of the covariance matrix $\matr \Sigma$ is also a symmetric matrix, its square root can be found – based on Eq. \eqref{eq:sqrtSymMatrix} – to be a symmetric matrix. In this case we can write the squared Mahalanobis distance as

\[\begin{align*} D &= (\matr X -\vec \mu )^\tp \matr \Sigma^{-1} (\matr X - \vec \mu ) = (\matr X -\vec \mu )^\tp \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} (\matr X - \vec \mu )\\ &= \Big( \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} (\matr X -\vec \mu ) \Big)^\tp \Big(\matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} (\matr X - \vec \mu ) \Big) = \matr Y^\tp \matr Y = ||\matr Y||^2 \\ &= \sum_{k=1}^\ell Y_k^2 \end{align*}\]The multiplication $\matr Y = \matr W \matr Z$, with $\matr W=\matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}}$ and $\matr Z= \matr X -\vec \mu $ is typically referred to as a whitening transform, where in this case $\matr W=\matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}}$ is the so called Mahalanobis (or ZCA) whitening matrix. $\matr Y$ has zero mean, since $(\matr X - \vec \mu ) \thicksim N(\vec 0,\Sigma)$. Due to the (linear) whitening transform the new covariance matrix $\matr \Sigma_y$ is the identity matrix $\matr I$, as shown in the following (using the property in Eq. \eqref{eq:AffineLinearTransformCovariance}):

\[\begin{align*} \matr \Sigma_y &= \matr W \matr \Sigma \matr W^\tp = \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \matr \Sigma \Big( \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \Big)^\tp = \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \Big(\matr \Sigma^{\frac{1}{2}}\matr \Sigma^{\frac{1}{2}} \Big) \Big( \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \Big)^\tp \\ &= \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \Big(\matr \Sigma^{\frac{1}{2}}\matr \Sigma^{\frac{1}{2}} \Big) \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} = \Big(\matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}} \matr \Sigma^{\frac{1}{2}} \Big) \Big(\matr \Sigma^{\frac{1}{2}} \matr \Sigma^{-\frac{1}{2}}\Big)\\ &= \matr I. \end{align*}\]Hence, all elements $Y_k$ in the random vector $\matr Y$ are random variables drawn from independent normal distributions $Y_k \thicksim N(0,1)$, which leads us to the same conclusion as before, that $D$ is Chi-square distributed with $\ell$ degrees of freedom.

Conclusion

We have shown that the squared Mahalanobis distance of a Gaussian random vector follows a Chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the dimension of the data.

This result has a very practical consequence: it allows us to replace heuristic or Monte Carlo–based thresholding with an exact statistical criterion.

In anomaly detection, instead of deciding “by hand” where to cut off the probability density, we can set thresholds directly using the quantiles of the Chi-square distribution.

For example, in $\ell$ dimensions, the 95% confidence region of a Gaussian distribution is exactly the ellipsoid

This means we can flag data points outside this ellipsoid as anomalies with a well-defined false alarm rate.

More generally, the Mahalanobis distance provides a natural way to measure how unusual a point is relative to a multivariate distribution. Combined with the Chi-square connection, it gives both a geometric intuition (ellipsoids of equal distance) and a rigorous statistical tool for multivariate analysis.

👉 A more detailed exploration of the Mahalanobis distance — including multiple Python implementations, benchmarks, and visualizations — is covered in a separate blog post here.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: