Backpropagation from Scratch: Feed-Forward Neural Networks in Matrix Notation

- Introduction

- Notation Guide

- Classical Feed-Forward Neural Network Architecture

- The Feed-Forward Pass

- The Backpropagation Algorithm

- Putting Everything Together (Full-Batch, Vectorized)

- Accompanying Jupyter Notebook (Code Companion)

\( \renewcommand{\vec}[1]{\boldsymbol{\mathbf{#1}}} \def\matr#1{\boldsymbol{\mathbf{#1}}} \def\Wmatr{\matr{W}} \newcommand{\din}{\mathord{d_0}} \newcommand{\batch}{\mathord{N}} \newcommand{\yhat}{\vec{\hat{y}}} \)

Introduction

Neural networks have been explained a thousand times — so why another intro?

Because for many people (my past self included) the hard part isn’t “deep math”, it’s getting the nuts and bolts of training straight: what exactly happens in the forward pass, where the gradients come from, and how backpropagation is really just an efficient, structured application of the chain rule that makes gradient descent practical.

The basics are also the best entry point: once you understand a plain fully connected feed-forward network end to end, the same ideas carry over to CNNs, recurrent nets, and even transformers. In my experience, neural networks are not conceptually difficult - the main obstacle is notation. At the end of the day it’s often “notation, notation, notation” (and much less multivariate calculus than it first appears).

That’s why this post takes a deliberately “from scratch” approach: we build a mathematical formulation step by step (single weight → vectors/matrices → batches), derive backpropagation in a way that matches an implementation, and then implement a small network accordingly. Along the way we also cover practical details that matter in real code, such as weight initialization and gradient checking, to make sure training works and the derivations actually hold up in practice.

Notation Guide

The following table summarizes all symbols and notation used throughout this post. Vectors are written in bold lowercase, matrices in bold uppercase, and scalars in regular font. Unless stated otherwise, vectors are column vectors.

| Symbol | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| $L$ | scalar | Number of parameterized (trainable) layers in the network |

| $\ell$ | index | Layer index, $\ell = 0,1,\ldots,L$ |

| $\din$ | scalar | Input dimension of the network |

| $d_L$ | scalar | Output dimension of the network |

| $d_\ell$ | scalar | Number of neurons in layer $\ell$ |

| $\batch$ | scalar | Batch size (number of training examples processed in parallel) |

| $\vec{x}$ | vector | Single input vector $\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{\din}$ |

| $\vec{x}_n$ | vector | $n$-th input vector in a batch |

| $\matr X$ | matrix | Input batch matrix, $\matr X \in \mathbb{R}^{\din \times \batch}$ |

| $a_i^{(\ell)}$ | scalar | Activation of neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$ |

| $\vec a^{(\ell)}$ | vector | Activation vector of layer $\ell$ for a single example |

| $\vec a_n^{(\ell)}$ | vector | Activation vector at layer $\ell$ for the $n$-th example |

| $\matr A^{(\ell)}$ | matrix | Activation matrix at layer $\ell$, $\matr A^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}$ |

| $z_i^{(\ell)}$ | scalar | Pre-activation of neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$ |

| $\vec z^{(\ell)}$ | vector | Pre-activation vector of layer $\ell$ (single example) |

| $\matr Z^{(\ell)}$ | matrix | Pre-activation matrix of layer $\ell$ (batch) |

| $w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}$ | scalar | Weight connecting neuron $j$ in layer $\ell-1$ to neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$ |

| $\vec w^{(\ell)}_{i}$ | vector | Incoming weight vector of neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$ |

| $\Wmatr^{(\ell)}$ | matrix | Weight matrix of layer $\ell$, $\Wmatr^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}$ |

| $b_i^{(\ell)}$ | scalar | Bias of neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$ |

| $\vec b^{(\ell)}$ | vector | Bias vector of layer $\ell$, $\vec b^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell}$ |

| $\sigma(\cdot)$ | function | Activation function (applied element-wise) |

| $\sigma’(\cdot)$ | function | Derivative of the activation function |

| $\hat{\vec y}$ | vector | Network output for a single input |

| $\hat{\vec y}_n$ | vector | Predicted output for the $n$-th training example |

| $\matr{\hat{Y}}$ | matrix | Output matrix of the network for a batch |

| $\vec y_n^*$ | vector | True target/output for the $n$-th training example |

| $\matr Y^*$ | matrix | Target output matrix for a batch |

| $\mathcal{L}_n$ | scalar | Loss for the $n$-th training example |

| $\mathcal{L}(\vec y^*, \hat{\vec y})$ | scalar | Loss function for a single example |

| $J(\Theta)$ | scalar | Cost function (average loss over a batch) |

| $\Theta$ | set | Set of all trainable parameters of the network |

| $\delta_i^{(\ell)}$ | scalar | Error signal (loss derivative w.r.t. $z_i^{(\ell)}$) |

| $\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)}$ | vector | Error vector at layer $\ell$ (single example) |

| $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$ | matrix | Error matrix at layer $\ell$ for a batch |

| $\otimes$ | operator | Hadamard (element-wise) product |

| $\vec 1$ | vector | Vector of ones, $\vec 1 \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}$ |

| $\eta$ | scalar | Learning rate |

| $\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}$ | matrix | Gradient of the cost w.r.t. weights of layer $\ell$ |

| $\frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}$ | vector | Gradient of the cost w.r.t. biases of layer $\ell$ |

| $(\cdot)^\top$ | operator | Matrix or vector transpose |

Conventions

- All vectors are column vectors unless explicitly stated otherwise.

- Batch data is stacked column-wise.

- Activation functions and their derivatives are applied element-wise.

- Gradients are derived using the denominator-layout convention for matrix calculus.

Classical Feed-Forward Neural Network Architecture

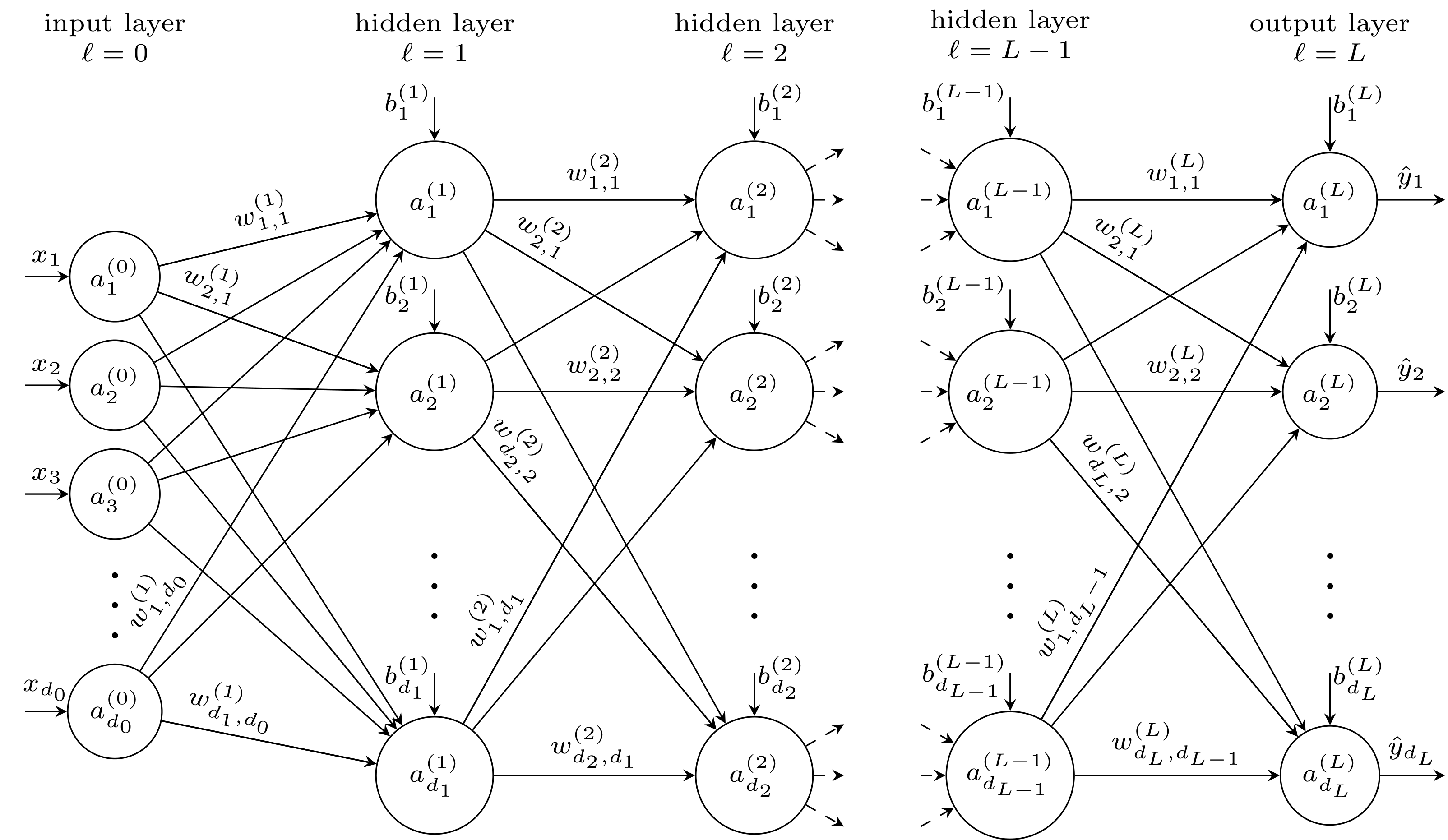

Figure 1 illustrates the general structure of a typical fully connected feed-forward neural network. The network consists of $L$ parameterized feed-forward layers with trainable weights, starting with the first hidden layer at $\ell = 1$ and ending with the output layer at $\ell = L$.

In total, the network comprises $L + 1$ layers, since the input is treated as an additional layer at $\ell = 0$. This input layer does not contain trainable parameters but serves to provide the input values to the network. The layer at $\ell = L$ is the output layer, while the layers with indices $1 \le \ell < L$ are referred to as hidden layers. The input to the network is given by the vector $\vec{x} = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{\din})^\top \in \mathbb{R}^{\din}$, where $\din$ denotes the input dimension. In the input layer, the components of $\vec{x}$ are identified with the activations $a_i^{(0)} = x_i$. Throughout this work, a superscript $(\ell)$ is used to indicate that a quantity is associated with layer $\ell$.

Each layer $\ell$ consists of $d_\ell$ neurons, where $d_0 = \din$ corresponds to the input dimension and $d_L$ denotes the output dimension of the network. In Figure 1, neurons are depicted as circles with incoming arrows. A neuron (also referred to as a node or unit) is the fundamental computational element of a neural network. It receives inputs from the preceding layer, forms a weighted sum of these inputs, adds a bias term, and subsequently applies a nonlinear activation function to produce its output. The output of the $i$-th neuron in layer $\ell$ is typically referred to as the activation $a_i^{(\ell)}$.

The neurons of adjacent layers are fully connected, meaning that each neuron in layer $\ell - 1$ is connected to every neuron in layer $\ell$. The weight $w^{(\ell)}_{i,j}$ denotes the trainable parameter connecting the $j$-th neuron of layer $\ell - 1$ to the $i$-th neuron of layer $\ell$. Bias terms are associated with each neuron in layers $\ell \ge 1$. For a given layer $\ell$, the bias term $b_i^{(\ell)}$ corresponds to the $i$-th neuron and is added to the weighted sum of its inputs before the activation function is applied.

The activations of the output layer, $a_i^{(L)}$, constitute the network output and are commonly denoted by $\hat{y}_i$, as indicated in Figure 1.

The Feed-Forward Pass

The Activation of a Neuron

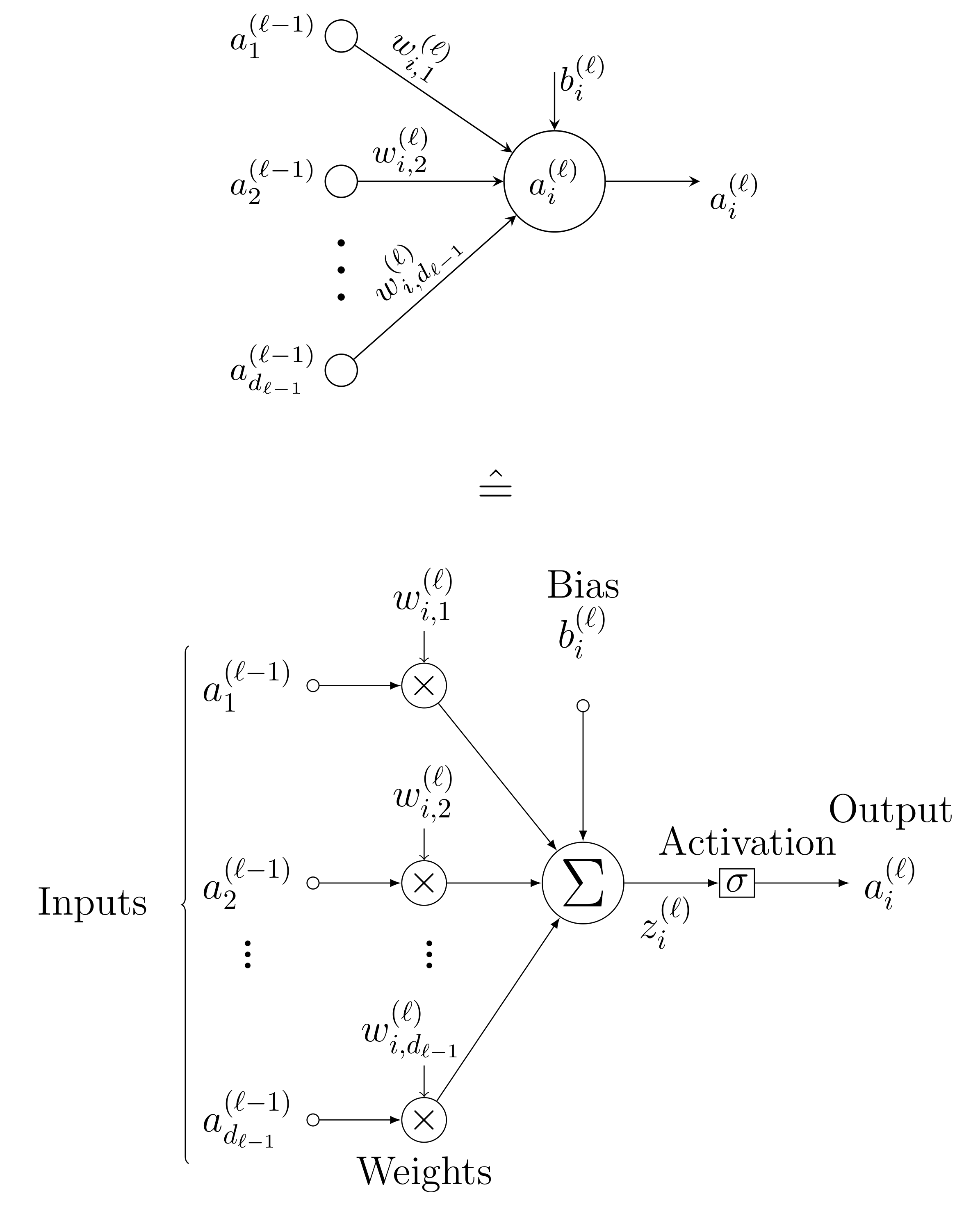

Figure 2 illustrates the internal structure of a neuron, including the weighted summation of its inputs, the addition of a bias term, and the subsequent application of a (nonlinear) activation function.

The neuron receives as inputs the activations \(a^{(\ell-1)}_1, a^{(\ell-1)}_2, \ldots, a^{(\ell-1)}_{d_{\ell-1}}\) from all neurons in the preceding layer $\ell - 1$. Each input activation \(a^{(\ell-1)}_j\) is multiplied by a corresponding trainable weight $w^{(\ell)}_{i,j}$, where the index $i$ denotes the neuron in the current layer and $j$ denotes the neuron in the previous layer. These multiplications are indicated by the multiplication symbols ($\times$) in the diagram.

The weighted inputs are then summed, as represented by the summation node ($\sum$). In addition, a bias term $b_i^{(\ell)}$, which is specific to the $i$-th neuron in layer $\ell$, is added to this sum. The resulting quantity,

\[z_i^{(\ell)} = \sum_{j=1}^{d_{\ell-1}} w^{(\ell)}_{i,j} \, a^{(\ell-1)}_j + b_i^{(\ell)},\]is referred to as the pre-activation of the neuron.

Finally, the pre-activation $z_i^{(\ell)}$ is passed through a nonlinear activation function $\sigma(\cdot)$, producing the output (or activation)

\[\begin{equation} a_i^{(\ell)} = \sigma\!\left(z_i^{(\ell)}\right) = \sigma \Bigg( \sum_{j=1}^{d_{\ell-1}} {w_{i,j}^{(\ell)} \cdot a_j^{(\ell-1)} } + b_i^{(\ell)} \Bigg) \label{eq:activation} \end{equation}\]This activation constitutes the output of the neuron and serves as an input to the neurons in the subsequent layer $\ell + 1$.

The Activation of a Layer of Neurons

The figure thus highlights the three fundamental steps performed by a neuron during the forward pass: weighted summation of inputs, addition of a bias term, and application of a nonlinear activation function.

In matrix form, Eq. \eqref{eq:activation} can be written as

\[\begin{equation} \vec a^{(\ell)} = \sigma\left(\vec z^{(\ell)}\right) = \sigma\left( \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \vec a^{(\ell-1)} + \vec b^{(\ell)} \right), \label{eq:activation3} \end{equation}\]where all vectors are interpreted as column vectors:

\[\begin{align} \vec a^{(\ell)}, \vec z^{(\ell)}, \vec b^{(\ell)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell}, \\ \Wmatr^{(\ell)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}, \\ \vec a^{(\ell-1)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell-1}}. \label{eq:activation4} \end{align}\]The activation function $\sigma(\cdot)$ is applied element-wise to its vector argument.

It is also possible to pass multiple input vectors through the network simultaneously by stacking them into a matrix. Let

\[\vec{x}_1, \vec{x}_2, \ldots, \vec{x}_\batch\]denote $\batch$ input examples, where $\batch$ is referred to as the batch size. These inputs are arranged column-wise into the input matrix

\[\begin{align} \matr X &= \big( \vec{x}_1 \ \vec{x}_2 \ \ldots \ \vec{x}_\batch \big), \\ \matr X &\in \mathbb{R}^{\din \times \batch}. \label{eq:input-matrix} \end{align}\]This procedure is commonly referred to as batching. A matrix containing multiple input vectors is called a batch.

In some implementations, input vectors are stacked row-wise, with each row representing one example. Here, we adopt the column-wise convention, which is consistent with the preceding vector notation and the matrix formulations used throughout.

For each input example $\vec{x}_n$, a corresponding activation vector $\vec{a}_n^{(\ell)}$ is produced at layer $\ell$. These activations can be collected into the activation matrix

\[\matr A^{(\ell)} = \big( \vec a_1^{(\ell)} \ \vec a_2^{(\ell)} \ \ldots \ \vec a_\batch^{(\ell)} \big) \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}.\]Using matrix notation, the forward pass for a batch of inputs can be written as

\[\begin{align} \matr Z^{(\ell)} &= \begin{pmatrix} \vec b^{(\ell)} & \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \vec{1}^\top \\ \matr A^{(\ell-1)} \end{pmatrix}, \\ &= \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \matr A^{(\ell-1)} + \vec b^{(\ell)} \vec 1^\top \\ \matr A^{(\ell)} &= \sigma\!\left( \matr Z^{(\ell)} \right), \label{eq:input-matrix1} \end{align}\]where $\vec{1} \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}$ denotes a vector of ones.

Note that the inclusion of the bias vector into the weight matrix is a purely notational convenience. From a mathematical perspective, the bias term can equivalently be added as a separate vector after the weighted sum has been computed. By augmenting the input with a constant component equal to one and concatenating the bias vector to the weight matrix, the affine transformation can be written as a single matrix multiplication. Throughout this post, this augmented representation is used where it simplifies the notation, but it does not constitute an additional modeling assumption.

Unpacking the Batch Forward Pass (Column-wise View)

To see explicitly how the augmented matrix multiplication works, we expand Eq. \eqref{eq:input-matrix1} using block-matrix multiplication:

\[\matr A^{(\ell-1)} = \begin{pmatrix} \vert & \vert & & \vert \\ \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{1} & \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{2} & \cdots & \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{\batch} \\ \vert & \vert & & \vert \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell-1}\times \batch}.\]Then the matrix multiplication expands as

\[\Wmatr^{(\ell)}\matr A^{(\ell-1)} = \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \begin{pmatrix} \vert & \vert & & \vert \\ \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{1} & \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{2} & \cdots & \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{\batch} \\ \vert & \vert & & \vert \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \vert & \vert & & \vert \\ \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{1} & \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{2} & \cdots & \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{\batch} \\ \vert & \vert & & \vert \end{pmatrix}.\]To add the bias to every column, we replicate it across the batch:

\[\vec b^{(\ell)}\vec 1^\top = \vec b^{(\ell)} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \vert & \vert & & \vert \\ \vec b^{(\ell)} & \vec b^{(\ell)} & \cdots & \vec b^{(\ell)} \\ \vert & \vert & & \vert \end{pmatrix}.\]Hence the pre-activation matrix becomes

\[\matr Z^{(\ell)} = \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\matr A^{(\ell-1)} + \vec b^{(\ell)}\vec 1^\top = \begin{pmatrix} \vert & \vert & & \vert \\ \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{1} + \vec b^{(\ell)} & \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{2} + \vec b^{(\ell)} & \cdots & \Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{\batch} + \vec b^{(\ell)} \\ \vert & \vert & & \vert \end{pmatrix}.\]Applying $\sigma(\cdot)$ element-wise yields the activation matrix

\[\begin{align*} \matr A^{(\ell)} = \sigma\!\left(\matr Z^{(\ell)}\right) &= \begin{pmatrix} \vert & \vert & & \vert \\ \sigma\!\big(\Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{1} + \vec b^{(\ell)}\big) & \sigma\!\big(\Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{2} + \vec b^{(\ell)}\big) & \cdots & \sigma\!\big(\Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{\batch} + \vec b^{(\ell)}\big) \\ \vert & \vert & & \vert \end{pmatrix} \\[12pt] &= \big( \vec a_1^{(\ell)} \ \vec a_2^{(\ell)} \ \ldots \ \vec a_\batch^{(\ell)} \big) \end{align*}\]So each column is exactly the single-example relation we already wrote:

\[\vec a^{(\ell)}_{n} = \sigma\!\left(\vec z^{(\ell)}_{n}\right) = \sigma\!\left(\Wmatr^{(\ell)}\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_{n} + \vec b^{(\ell)}\right), \qquad n=1,\ldots,\batch.\]Computing the Activation of the first Hidden Layer

Using the augmented representation and $\matr A^{(0)}= \matr X$, the affine transformation of the first hidden layer can be written as

\[\begin{equation} \matr A^{(1)} = \sigma\!\left( \begin{pmatrix} \vec b^{(1)} & \Wmatr^{(1)} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \vec{1}^\top \\ \matr X \end{pmatrix} \right). \label{eq:input-matrix2} \end{equation}\]Here, the augmented weight matrix

\[\begin{pmatrix} \vec b^{(1)} & \Wmatr^{(1)} \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_1 \times (\din + 1)}\]is formed by concatenating the bias vector $\vec b^{(1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_1}$ and the weight matrix $\Wmatr^{(1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_1 \times \din}$, while the augmented input matrix

\(\begin{pmatrix} \vec{1}^\top \\ \matr X \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{(\din + 1) \times \batch}\) contains a row of ones and the input batch $\matr X \in \mathbb{R}^{\din \times \batch}$. As a result, the matrix product is well defined and yields

\[\matr A^{(1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_1 \times \batch}.\]Summary: Forward Pass Through the Network

We summarize the steps required to compute a forward pass for a batch of inputs through a fully connected feed-forward neural network. This provides a compact, algorithmic view of the computations introduced so far and serves as a reference for later gradient derivations.

Inputs and Parameters

- Network architecture

- Number of layers: $L$

- Layer sizes: $d_0=\din, d_1, \ldots, d_L$

- Trainable parameters (for each layer $\ell = 1,\ldots,L$)

- Weight matrix: $ \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}} $

- Bias vector: $ \vec b^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell} $

- Activation function

- Nonlinear function $\sigma(\cdot)$, applied element-wise

- Batch input

- $\batch$ input vectors stacked column-wise: \(\matr X = \matr A^{(0)} \in \mathbb{R}^{\din \times \batch}\)

Forward Pass

-

Initialization \(\matr A^{(0)} := \matr X\)

- Layer-wise propagation

For each layer $\ell = 1,2,\ldots,L$:-

Pre-activations: \(\matr Z^{(\ell)} = \begin{pmatrix} \vec b^{(\ell)} & \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \vec{1}^\top \\ \matr A^{(\ell-1)} \end{pmatrix}, \qquad \matr Z^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch},\)

where $\vec 1 \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}$ denotes a vector of ones.

Equivalently: $\matr Z^{(\ell)} = \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \matr A^{(\ell-1)} + \vec b^{(\ell)} \vec 1^\top$.

-

Activations: \(\matr A^{(\ell)} = \sigma\!\left(\matr Z^{(\ell)}\right), \qquad \matr A^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}\)

-

-

Network output \(\matr A^{(L)} = \big( \hat{\vec y}_1 \ \hat{\vec y}_2 \ \ldots \ \hat{\vec y}_\batch \big) ,\qquad \matr A^{(L)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_L \times \batch},\)

where $\hat{\vec y}_n \in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}$ denotes the output of the network for the $n$-th input example.

Each column of $\matr A^{(\ell)}$ corresponds to the activations produced by one training example, and the same weight matrices and bias vectors are shared across all columns.

Remarks

- The batch forward pass is mathematically equivalent to performing $\batch$ independent forward passes in parallel.

- Writing the computation in matrix form enables efficient implementations using linear algebra routines.

- All intermediate matrices \(\{\matr A^{(\ell)}, \matr Z^{(\ell)}\}_{\ell=1}^L\) must be retained, as they are required later during backpropagation.

This completes the forward-pass specification for batched inputs.

The Backpropagation Algorithm

Cost Function and Gradient Descent

To train the neural network, a suitable differentiable cost (sometimes objective) function $J(\Theta)$ is required, where $\Theta$ denotes the set of all trainable parameters of the network, including both the weight matrices and the bias vectors of all layers. Explicitly, we write

\[\Theta = \left\{ \Wmatr^{(1)}, \vec b^{(1)}, \Wmatr^{(2)}, \vec b^{(2)}, \ldots, \Wmatr^{(L)}, \vec b^{(L)} \right\}.\]We denote the loss for a single ($n$-th) training example by $\mathcal{L}(\vec y_n^*, \hat{\vec y_n})$. A commonly used choice is the mean squared error (MSE) loss, which measures the prediction error for a single training example. For an individual example $n$, the loss is defined as

\[\mathcal{L}_n = \frac{1}{2}\left\| \vec{y}_n^* - \hat{\vec y}_n \right\|^2,\]where $\vec y_n^* \in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}$ denotes the true output vector of the $n$-th example and $\hat{\vec y}_n = \vec a_n^{(L)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}$ is the corresponding predicted output of the network.

Note.

The factor $\tfrac{1}{2}$ is included purely for convenience. When differentiating the squared error, it cancels the factor $2$ arising from the derivative of the square and thus simplifies the resulting gradient expressions. Importantly, this factor does not affect the location of the minimum of the cost function.

The cost function $J(\Theta)$ is obtained by aggregating the loss over a batch of $\batch$ training examples. Using the mean squared error, the cost function is given by

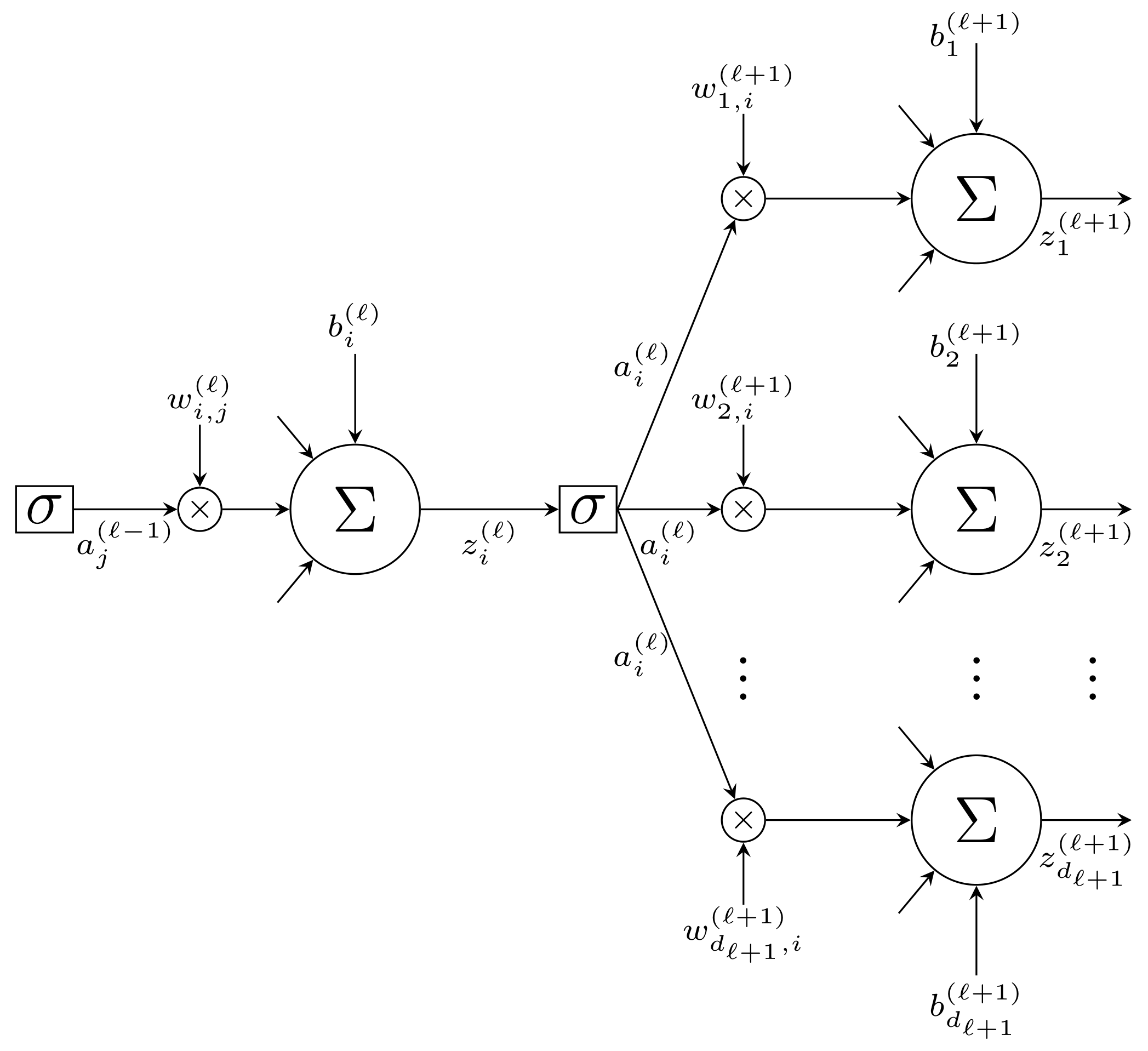

\[J(\Theta) = \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \mathcal{L}_n = \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \frac{1}{2}\left\| \vec{y}_n^* - \hat{\vec y}_n \right\|^2. \label{eq:mse}\]In Figure 3, the local structure of two consecutive layers in a feed-forward neural network is illustrated in a form that is particularly useful for deriving the backpropagation algorithm. The figure highlights a single neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$, its pre-activation $z_i^{(\ell)}$, and its activation

\[a_i^{(\ell)} = \sigma\left(z_i^{(\ell)}\right),\]as well as how this activation is propagated forward to all neurons in the subsequent layer $\ell + 1$.

Specifically, the activation $a_i^{(\ell)}$ serves as an input to each neuron in layer $\ell + 1$, where it is multiplied by the corresponding weights $w_{k,i}^{(\ell+1)}$, summed together with the other incoming weighted activations, and combined with the bias terms $b_k^{(\ell+1)}$ to form the pre-activations $z_k^{(\ell+1)}$. This explicit depiction makes clear how a single activation influences multiple downstream neurons and, conversely (as we will see below), how gradients computed at layer $\ell + 1$ will later be propagated backward through the same weighted connections to layer $\ell$.

Gradient descent can be used to minimize the cost function $J(\Theta)$. This requires computing the partial derivatives of $J$ with respect to all trainable parameters contained in $\Theta$. Due to the layered structure of a neural network, these derivatives cannot be computed directly in a single step. Figure 3 illustrates this dependency structure for a specific weight $w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}$.

At this point, it is convenient to distinguish between the loss $\mathcal{L}(\vec y^*, \hat{\vec y})$ of a single training example and the cost function $J(\Theta)$, which aggregates the loss over a batch of $\batch$ examples. The derivation of backpropagation is carried out at the single-sample level, since differentiation is a linear operation. In particular, if

\[J(\Theta) = \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \mathcal{L}_n(\Theta),\]then the gradient of the cost function is given by

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Theta} = \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}_n}{\partial \Theta}.\]Thus, the gradient of $J$ is simply the average of the gradients of the individual losses. For this reason, we first derive the gradients of the loss for a single training example and later extend the result to a batch by averaging.

Assume that we want to compute the partial derivative of the loss function with respect to the weight $w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}$. Since this weight influences the loss only indirectly through the pre-activation $z_i^{(\ell)}$ of neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$, the chain rule yields

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} \frac{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}}. \label{eq:partial1} \end{align}\]From the definition of the pre-activation

\[z_i^{(\ell)} = \sum_{j} w_{i,j}^{(\ell)} a_j^{(\ell-1)} + b_i^{(\ell)},\]it follows immediately that

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} = a_j^{(\ell-1)}. \label{eq:partial2} \end{align}\]Substituting this result into Eq. \eqref{eq:partial1} yields

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} \, a_j^{(\ell-1)}. \end{align}\]So far, we have considered the partial derivative of the loss with respect to the weights $w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}$. An analogous and even simpler expression is obtained for the bias parameters $b_i^{(\ell)}$.

Since the bias enters the pre-activation additively, we have

\[\frac{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} = 1.\]Therefore, by the chain rule,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} \frac{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} \\ &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}. \end{align}\]In summary, we have:

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} \, a_j^{(\ell-1)}, \label{eq:partial3} \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}. \label{eq:partial3_b} \end{align}\]The remaining partial derivative $\partial \mathcal{L} / \partial z_i^{(\ell)}$ cannot be evaluated directly. However, it can be expressed recursively by applying the chain rule, which forms the basis of the backpropagation algorithm.

Interlude: The Chain Rule and Nested Dependencies

Before deriving the backpropagation algorithm, it is helpful to briefly recall the chain rule for derivatives, which plays a central role in computing gradients in neural networks. In particular, neural networks are composed of nested functions, so changes in a parameter typically affect the output only indirectly through a sequence of intermediate variables.

Consider a function $z = f(x, y)$ that depends on two intermediate variables $x$ and $y$, which in turn both depend on a common variable $t$, i.e.

\[x = g(t), \qquad y = h(t).\]In this case, the total derivative of $z$ with respect to $t$ is given by the chain rule as

\[\begin{align} z &= f(x, y), \quad x = g(t), \quad y = h(t), \\ \frac{d z}{d t} &= \frac{\partial z}{\partial x} \frac{d x}{d t} + \frac{\partial z}{\partial y} \frac{d y}{d t}. \label{eq:chainrule1} \end{align}\]This expression shows that the influence of $t$ on $z$ is obtained by summing all paths through which $t$ affects the intermediate variables $x$ and $y$.

Consider the composite function

\[z = \sin(x^2 + y^2), \qquad x = e^t, \qquad y = t^2.\]Since $z$ depends on $t$ only through the intermediate variables $x$ and $y$, the chain rule gives

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial z}{\partial x} &= 2x \cos(x^2 + y^2), \\ \frac{\partial z}{\partial y} &= 2y \cos(x^2 + y^2), \\ \frac{d x}{d t} &= e^t, \\ \frac{d y}{d t} &= 2t. \end{align}\]Therefore, the total derivative of $z$ with respect to $t$ is

\[\begin{align} \frac{d z}{d t} &= 2x \cos(x^2 + y^2)\,\frac{d x}{d t} + 2y \cos(x^2 + y^2)\,\frac{d y}{d t} \\ &= 2x \cos(x^2 + y^2)\,e^t + 2y \cos(x^2 + y^2)\,2t \\ &= 2\cos(x^2 + y^2)\left(x\,e^t + 2yt\right) \\ &= 2\cos\left(e^{2t} + t^4\right)\left(e^{2t} + 2t^3\right). \end{align}\]Using direct differentiation, we obtain

\[\begin{align} z &= \sin(e^{2t} + t^4), \\ \frac{d z}{d t} &= \cos(e^{2t} + t^4)\left(2 e^{2t} + 4 t^3\right) \\ &= 2\cos(e^{2t} + t^4)\left(e^{2t} + 2 t^3\right), \end{align}\]which is identical to the result obtained via the chain rule.

Similarly, an analogous form of the chain rule applies when the intermediate variables are vector-valued. Let $\vec t$ be a vector and let $z = f(\vec x)$ with $\vec x = g(\vec t)$. Then the partial derivative of $z$ with respect to the $i$-th component of $\vec t$ is given by

\[\begin{align} z &= f(\vec{x}), \qquad \vec{x} = g(\vec{t}), \\ \frac{\partial z}{\partial t_i} &= \frac{\partial z}{\partial x_1} \frac{\partial x_1}{\partial t_i} + \frac{\partial z}{\partial x_2} \frac{\partial x_2}{\partial t_i} + \cdots \\ &= \sum_{j} \frac{\partial z}{\partial x_j} \frac{\partial x_j}{\partial t_i}. \label{eq:chainrule2} \end{align}\]This expression shows that the influence of a single component $t_i$ on $z$ is obtained by summing over all paths through which $t_i$ affects the intermediate variables $\vec x$.

Backpropagation via the Chain Rule

We can now use the chain rule to compute the partial derivative $\partial \mathcal{L} / \partial z_i^{(\ell)}$ in Eq. \eqref{eq:partial3} & Eq. \eqref{eq:partial3_b} in a recursive manner. As illustrated in Figure 3, the pre-activations $z_k^{(\ell+1)}$ of the next layer can be regarded as functions of the pre-activations of the current layer, in particular of $z_i^{(\ell)}$, i.e., $z_k^{(\ell+1)} = z_k^{(\ell+1)}(\ldots, z_i^{(\ell)}, \ldots)$. Consequently, the loss function depends on $z_i^{(\ell)}$ only indirectly through its influence on all downstream pre-activations $z_k^{(\ell+1)}$. Formally, one may therefore view the loss function as a composite function of the form $\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}\big(\ldots, z_k^{(\ell+1)}(\ldots, z_i^{(\ell)}, \ldots), \ldots\big)$, which naturally leads to a recursive application of the chain rule.

Applying the chain rule, we obtain

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_1^{(\ell+1)}} \frac{\partial z_1^{(\ell+1)}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_2^{(\ell+1)}} \frac{\partial z_2^{(\ell+1)}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} + \cdots \\ &= \sum_{k=1}^{d_{\ell+1}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_k^{(\ell+1)}} \frac{\partial z_k^{(\ell+1)}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}. \label{eq:chainrule3} \end{align}\]From the definition

\[z_k^{(\ell+1)} = \sum_j w^{(\ell+1)}_{k,j} a_j^{(\ell)} + b_k^{(\ell+1)}, \qquad a_j^{(\ell)} = \sigma\!\left(z_j^{(\ell)}\right),\]it follows that

\[\frac{\partial z_k^{(\ell+1)}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} = w^{(\ell+1)}_{k,i} \, \sigma'\!\left(z_i^{(\ell)}\right),\]where $\sigma’(z)$ denotes the derivative of the activation function $\sigma(\cdot)$ with respect to its argument.

Substituting this result into Eq. \eqref{eq:chainrule3} yields

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} = \sigma'\!\left(z_i^{(\ell)}\right) \sum_{k=1}^{d_{\ell+1}} w^{(\ell+1)}_{k,i} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_k^{(\ell+1)}}. \label{eq:backprop-recursion} \end{align}\]Note the recursive structure of Eq. \eqref{eq:backprop-recursion}. For notational convenience, we define the error signal (also called the delta term), i.e. the gradient of the loss with respect to the pre-activation, at neuron $i$ in layer $\ell$ as

\[\delta_i^{(\ell)} := \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}.\]With this definition, Eq. \eqref{eq:backprop-recursion} can be written in the recursive form

\[\begin{align} \delta_i^{(\ell)} &= \sigma'\!\left(z_i^{(\ell)}\right) \sum_{k=1}^{d_{\ell+1}} w^{(\ell+1)}_{k,i}\, \delta_k^{(\ell+1)}. \label{eq:chainrule4} \end{align}\]Equation \eqref{eq:chainrule4} can be written in a more compact vector form. To this end, we introduce the error vectors

\[\begin{align} \vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell }, \\ \vec{\delta}^{(\ell+1)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell+1} }, \end{align}\]and the weight matrix

\[\begin{align} \Wmatr^{(\ell+1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell+1} \times d_\ell}. \label{eq:chainrule6} \end{align}\]In Eq.\eqref{eq:chainrule4}, the summation is carried out over the index $k$, which corresponds to the first index of the weight $w_{k,i}^{(\ell+1)}$. This implies that, in matrix notation, the transpose of $\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)}$ must be used. Indeed, we have

\[\begin{align} (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell+1}}, \\ (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \vec{\delta}^{(\ell+1)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell }. \label{eq:chainrule7} \end{align}\]To see how the transpose arises explicitly, write the weight matrix row-wise as

\[\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)} = \begin{pmatrix} (\vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{1})^\top \\ (\vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{2})^\top \\ \vdots \\ (\vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{d_{\ell+1}})^\top \end{pmatrix}, \qquad \vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{k} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell},\]i.e., the $k$-th row contains the incoming weights of neuron $k$ in layer $\ell+1$. Taking the transpose yields

\[(\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top = \begin{pmatrix} \vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{1} & \vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{2} & \cdots & \vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{d_{\ell+1}} \end{pmatrix}.\]Now let

\[\vec\delta^{(\ell+1)} = \begin{pmatrix} \delta^{(\ell+1)}_{1}\\ \delta^{(\ell+1)}_{2}\\ \vdots\\ \delta^{(\ell+1)}_{d_{\ell+1}} \end{pmatrix}.\]Then the matrix-vector product can be interpreted as a weighted sum of the (transposed) row vectors:

\[(\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \vec\delta^{(\ell+1)} = \sum_{k=1}^{d_{\ell+1}} \vec w^{(\ell+1)}_{k}\,\delta^{(\ell+1)}_{k}.\]Looking at the $i$-th component of this vector gives

\[\big[(\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \vec\delta^{(\ell+1)}\big]_i = \sum_{k=1}^{d_{\ell+1}} w^{(\ell+1)}_{k,i}\,\delta^{(\ell+1)}_{k},\]which is exactly the summation term appearing in Eq. \eqref{eq:chainrule4}.

Using this notation (following the denominator-layout convention) and writing the derivative of the activation function element-wise, the backpropagation recursion can be expressed as

\[\begin{align} \vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} := \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \vec z^{(\ell)}} = \Big( (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \vec{\delta}^{(\ell+1)} \Big) \otimes \sigma'\!\left(\vec z^{(\ell)}\right), \label{eq:chainrule8} \end{align}\]where $\otimes$ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product and the derivative $\sigma’(\cdot)$ is applied component-wise to the vector $\vec z^{(\ell)}$.

Recall Eqs. \eqref{eq:partial3} and \eqref{eq:partial3_b}, which give the gradients of the loss with respect to the weights and biases of layer $\ell$:

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}} \, a_j^{(\ell-1)}, \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(\ell)}}. \end{align}\]By comparison with Eq. \eqref{eq:chainrule8}, we immediately obtain

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} &= \delta_i^{(\ell)} \, a_j^{(\ell-1)}, \label{eq:finalbackprop} \\ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} &= \delta_i^{(\ell)} \label{eq:finalbackprop_b} \end{align}\]Thus, once the error signal $\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)}$ has been computed for a given layer, the gradients with respect to both the weights and the biases follow directly. These observations naturally lead to compact matrix expressions for the gradients with respect to the weight matrices and bias vectors, which we derive next.

From the component-wise relations

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}} = \delta_i^{(\ell)}\, a_j^{(\ell-1)}, \qquad \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial b_i^{(\ell)}} = \delta_i^{(\ell)},\]we can derive compact matrix-vector expressions for the gradients with respect to the weight matrix $\Wmatr^{(\ell)}$ and the bias vector $\vec b^{(\ell)}$.

Gradient with respect to the weights (vectorized form)

Collecting all partial derivatives $\partial \mathcal{L}/\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}$ into a matrix yields

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} &= \vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} \, \big(\vec a^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top. \label{eq:finalbackprop2} \end{align}\]The transpose arises because $\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)}$ and $\vec a^{(\ell-1)}$ are column vectors. With the (column-vector) convention used throughout,

\[\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times 1}, \qquad \vec a^{(\ell-1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell-1} \times 1}.\]To obtain a matrix in $\mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}$, we must form an outer product: the first factor stays a column vector, while the second is transposed into a row vector:

\[\big(\vec a^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times d_{\ell-1}}.\]Thus the dimensions match as

\[\begin{align} \vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} \, \big(\vec a^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times 1}\;\cdot\;\mathbb{R}^{1 \times d_{\ell-1}} = \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}. \end{align}\]Equivalently, the $(i,j)$-th entry of this outer product is

\[\left[\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} \, (\vec a^{(\ell-1)})^\top\right]_{i,j} = \delta_i^{(\ell)}\, a_j^{(\ell-1)},\]which matches the component-wise gradient $\partial \mathcal{L}/\partial w_{i,j}^{(\ell)}$.

Gradient with respect to the biases (vectorized form)

The bias gradient collects the partial derivatives $\partial \mathcal{L}/\partial b_i^{(\ell)}$ into a vector:

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} &= \vec{\delta}^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times 1}. \label{eq:finalbackprop2_b} \end{align}\]Hence, once the error vector $\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)}$ has been computed via the backpropagation recursion \eqref{eq:chainrule8}, both gradients $\partial \mathcal{L}/\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}$ and $\partial \mathcal{L}/\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}$ follow immediately.

As before, we can propagate a batch of training examples through the network by collecting them column-wise into the input matrix

\[\matr X = \matr A^{(0)} \in \mathbb{R}^{\din \times \batch}.\]During the forward pass, each layer produces an activation matrix $\matr A^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}$, where the $n$-th column corresponds to the activations generated by the $n$-th training example. Proceeding layer by layer, we eventually obtain the output matrix $\matr A^{(L)}$.

In the derivation above, the gradients were computed for a single training example. To perform a batch update of the parameters, these gradients must be aggregated over all $\batch$ examples in the batch. Since differentiation is linear, this aggregation is achieved by summing (or averaging) the per-example gradients.

To this end, we collect the error vectors $\vec{\delta}^{(\ell)}$ of all training examples at layer $\ell$ into the error matrix

\[\matr\Delta^{(\ell)} = \big( \vec{\delta}_1^{(\ell)} \; \vec{\delta}_2^{(\ell)} \; \ldots \; \vec{\delta}_\batch^{(\ell)} \big) \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}.\]Analogously, we denote by \(\matr Z^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}\) the matrix of pre-activations at layer $\ell$.

Batch Backpropagation Recursion

Applying the single-sample recursion \eqref{eq:chainrule8} column-wise to all examples yields the batch version of backpropagation:

\[\begin{align} \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} &= \Big( (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)} \Big) \;\otimes\; \sigma'\!\left(\matr Z^{(\ell)}\right), \label{eq:matrixBackprop} \end{align}\]where the derivative $\sigma’(\cdot)$ is applied element-wise and $\otimes$ denotes the Hadamard product.

The dimensions involved are

\[\begin{align} (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell+1}}, \\ \matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell+1} \times \batch}, \\ \matr Z^{(\ell)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}, \end{align}\]so that

\[(\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch},\]and the element-wise multiplication with $\sigma’(\matr Z^{(\ell)})$ is well defined.

Batch gradients for weights and biases

Using the batch error matrix $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$, the gradients of the loss with respect to the parameters of layer $\ell$ can be written compactly as

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top, \label{eq:J_W_ell} \\[6pt] \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \vec 1, \label{eq:J_b_ell} \end{align}\]with the following dimensions:

\[\begin{align} \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}, \\ \matr A^{(\ell-1)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell-1} \times \batch}, \\ \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top &\in \mathbb{R}^{\batch \times d_{\ell-1}}, \\ \vec 1 &\in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}, \\ \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}, \\ \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell}. \end{align}\]Here, the weight gradient has the same shape as the weight matrix $\Wmatr^{(\ell)}$, and the bias gradient has the same shape as the bias vector $\vec b^{(\ell)}$, as required for gradient-based optimization.

The first expression Eq. \eqref{eq:J_W_ell} corresponds to summing the outer products $\vec{\delta}_n^{(\ell)} (\vec a_n^{(\ell-1)})^\top$ over all training examples, while the second expression in Eq. \eqref{eq:J_b_ell} reflects the fact that each bias gradient is obtained by summing the corresponding error signals across the batch.

These batch-wise expressions allow all gradients to be computed efficiently using matrix operations, which is crucial for practical implementations of backpropagation.

To make the batch expressions more explicit, we write out the matrices $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$ and $\matr A^{(\ell-1)}$ in terms of their column vectors.

The activation matrix of layer $\ell-1$ is given by

\[\matr A^{(\ell-1)} = \begin{pmatrix} \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_1 & \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_2 & \cdots & \vec a^{(\ell-1)}_\batch \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell-1} \times \batch},\]where

\[\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_n \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{\ell-1}}\]denotes the activation vector produced by the $n$-th training example at layer $\ell-1$.

Similarly, the error matrix at layer $\ell$ is

\[\matr\Delta^{(\ell)} = \begin{pmatrix} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_1 & \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_2 & \cdots & \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_\batch \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch},\]where each column

\[\vec\delta^{(\ell)}_n \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell}\]is the error signal corresponding to the $n$-th training example.

Taking the transpose of the activation matrix yields

\[\big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top = \begin{pmatrix} (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_1)^\top \\ (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_2)^\top \\ \vdots \\ (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_\batch)^\top \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch \times d_{\ell-1}}.\]Weight gradient as a sum of outer products

Using these explicit forms, the batch gradient with respect to the weight matrix can be expanded as

\[\begin{align} \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top &= \begin{pmatrix} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_1 & \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_2 & \cdots & \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_\batch \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_1)^\top \\ (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_2)^\top \\ \vdots \\ (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_\batch)^\top \end{pmatrix} \\[6pt] &= \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_n \, (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_n)^\top. \end{align}\]Thus, the gradient of the cost function with respect to the weights is

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top \\ &= \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_n \, (\vec a^{(\ell-1)}_n)^\top, \end{align}\]which is exactly the average of the single-sample gradients derived earlier.

Bias Gradient as a Sum of Error Signals

For the bias parameters, we multiply the error matrix by a vector of ones,

\[\vec 1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ \vdots \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}.\]This yields

\[\begin{align} \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \vec 1 &= \begin{pmatrix} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_1 & \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_2 & \cdots & \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_\batch \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ \vdots \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} = \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_n. \end{align}\]Therefore, the batch gradient with respect to the bias vector is

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \vec 1 \\ &= \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \vec\delta^{(\ell)}_n. \end{align}\]These expansions make explicit that the matrix-based batch formulas implement nothing more than an efficient summation (or averaging) of the per-example gradients, fully consistent with the definition of the cost function \(J(\Theta) = \frac{1}{\batch} \sum_{n=1}^{\batch} \mathcal{L}_n(\Theta).\)

Gradient Descent Parameter Updates

Once the gradients of the cost function $J(\Theta)$ with respect to all parameters have been computed (typically for a full batch or mini-batch; see the section on practial considerations for details), the weights and biases can be updated using a gradient-based optimizer. For standard (batch) gradient descent with learning rate $\eta>0$, the update rule for layer $\ell$ is

\[\begin{align} \Wmatr^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \Wmatr^{(\ell)} - \eta \, \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}, \label{eq:gd-update_1} \\ \vec b^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \vec b^{(\ell)} - \eta \, \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}. \label{eq:gd-update} \end{align}\]Using the batch-gradient expressions derived above, we have

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top, \\ \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} &= \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \vec 1, \end{align}\]where $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}$ collects the error vectors of layer $\ell$ for all $\batch$ examples and $\vec 1 \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}$ is a vector of ones. Substituting these gradients into \eqref{eq:gd-update_1} & \eqref{eq:gd-update} yields the explicit batch update rules

\[\begin{align} \Wmatr^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \Wmatr^{(\ell)} - \eta \,\frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top, \\ \vec b^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \vec b^{(\ell)} - \eta \,\frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \vec 1. \label{eq:gd-update-batch} \end{align}\]These updates are applied for $\ell = 1,2,\ldots,L$. In practice, $J$ is often computed over a mini-batch, so $\batch$ denotes the mini-batch size.

Implementation note (when to update).

In a standard backpropagation implementation, one first performs the full backward pass to compute all error signals $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$ (and thus all gradients) before updating any parameters. Updating weights prematurely would mix parameters from different stages of the backward pass and can lead to incorrect gradients.That said, with careful bookkeeping (e.g., storing the required activations and error signals, or recomputing them deterministically), updates can be scheduled in different ways. The safest approach is: compute all gradients first, then update. Implement this approach first and make sure everything is working as intended, before considering optimizations of the backpropagation algorithm.

Initialization of Backpropagation at the Output Layer

The recursive relations in Eqs. \eqref{eq:chainrule4} and \eqref{eq:chainrule8} express the error signal in layer $\ell$ in terms of the error signals in the subsequent layer $\ell+1$. Consequently, this recursion cannot be evaluated forward and must instead be initialized at the output layer $\ell = L$ and then propagated backward through the network.

This backward flow of error signals (from the output layer toward the input layer) is the origin of the term backpropagation.

Output-layer Error Signal (single training example)

We begin by computing the error signal for the output layer $\ell = L$. For the mean squared error (MSE) loss and a single training example, the error signal of the $i$-th output neuron is defined as

\[\begin{align} \delta_i^{(L)} &:= \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial z_i^{(L)}} \\[4pt] &= \frac{\partial}{\partial z_i^{(L)}} \left[ \frac{1}{2} \big(y_i^* - a_i^{(L)}\big)^2 \right] \\[4pt] &= \frac{\partial}{\partial z_i^{(L)}} \left[ \frac{1}{2} \big(y_i^* - \sigma(z_i^{(L)})\big)^2 \right] \\[4pt] &= -\big(y_i^* - \sigma(z_i^{(L)})\big)\, \sigma'\!\left(z_i^{(L)}\right) \\[4pt] &= \big(a_i^{(L)} - y_i^*\big)\, \sigma'\!\left(z_i^{(L)}\right)\\[4pt] &= \big(\yhat_i - y_i^*\big)\, \sigma'\!\left(z_i^{(L)}\right). \end{align}\]This expression provides the starting point for the recursive computation of error signals in all preceding layers.

Remark (Cross-entropy loss).

For the binary cross-entropy loss in combination with a sigmoid activation function in the output layer (or for the generalized cross-entropy loss with a softmax activation), the derivative of the activation function cancels with a corresponding term from the loss derivative. In this case, the output-layer error signal simplifies to $\delta_i^{(L)} = a_i^{(L)} - y_i^*.$ This simplification is one of the main reasons why cross-entropy loss is commonly preferred over mean squared error for classification tasks.

Vectorized Form (single training example)

Collecting the error signals of all output neurons into a vector yields

\[\begin{align} \vec{\delta}^{(L)} &= \big(\vec a^{(L)} - \vec y^*\big) \otimes \sigma'\!\left(\vec z^{(L)}\right) \\[4pt] &= \big(\hat{\vec y} - \vec y^*\big) \otimes \sigma'\!\left(\vec z^{(L)}\right), \label{eq:chainrule5} \end{align}\]with the following dimensions:

\[\begin{align} \vec{\delta}^{(L)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}, \\ \vec a^{(L)} = \hat{\vec y}, \vec y^* &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}, \\ \vec z^{(L)} &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}, \\ \sigma'\!\left(\vec z^{(L)}\right) &\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L}. \end{align}\]Here, $\otimes$ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product, and the derivative $\sigma’(\cdot)$ is applied component-wise to the pre-activation vector $\vec z^{(L)}$.

Vectorized Batch Formulation

When processing a batch of $\batch$ training examples, the individual output-layer error vectors $\vec{\delta}_n^{(L)}$ are collected column-wise into the batch error matrix

\[\begin{align} \matr\Delta^{(L)} &= \begin{pmatrix} \vec{\delta}_1^{(L)} & \vec{\delta}_2^{(L)} & \cdots & \vec{\delta}_\batch^{(L)} \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \big(\matr A^{(L)} - \matr Y^*\big)\ \otimes\ \sigma'\!\big(\matr Z^{(L)}\big) \\ &= \big(\matr{\hat{Y}} - \matr Y^*\big)\ \otimes\ \sigma'\!\big(\matr Z^{(L)}\big), \end{align}\]with $\matr\Delta^{(L)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_L \times \batch}$, the predictions

\[\matr{\hat{Y}} = \big(\vec{\yhat}_1 \ \ldots \ \vec{\yhat}_\batch \big)\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L \times \batch},\]and the targets (truth labels)

\[\matr Y^* = \big(\vec y_1^* \ \ldots \ \vec y_\batch^*\big)\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L \times \batch}.\]This matrix constitutes the initial condition for batch backpropagation. Starting from $\matr\Delta^{(L)}$, the error matrices of all preceding layers $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$ are obtained recursively using Eq. \eqref{eq:chainrule8}.

Summary: Backpropagation

We summarize the steps required to compute all gradients of the cost function $J(\Theta)$ for a batch of $\batch$ training examples using backpropagation. The resulting gradients can then be used in a gradient-descent update.

Inputs and Stored Quantities

- Network architecture

- Number of layers: $L$

- Layer sizes: $d_0=\din, d_1, \ldots, d_L$

- Trainable parameters (for each layer $\ell=1,\ldots,L$)

- $\Wmatr^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}$

- $\vec b^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell}$

- Batch data

- Inputs: $\matr X = \matr A^{(0)} \in \mathbb{R}^{\din \times \batch}$

- Targets: $\matr Y^* = \big(\vec y_1^* \ \ldots \ \vec y_\batch^*\big)\in \mathbb{R}^{d_L \times \batch}$

- Forward-pass cache (must be available from the forward pass)

- Activations: $\matr A^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}$ for $\ell=0,\ldots,L$

- Pre-activations: $\matr Z^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}$ for $\ell=1,\ldots,L$

- Element-wise operations

- $\sigma(\cdot)$ and $\sigma’(\cdot)$ are applied element-wise

- $\otimes$ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product

- $\vec 1 \in \mathbb{R}^{\batch}$ denotes a vector of ones

Backward Pass: Error Signals

-

Initialize at the output layer ($\ell=L$)

For mean squared error (MSE), \(\matr\Delta^{(L)} = \big(\matr A^{(L)} - \matr Y^*\big)\ \otimes\ \sigma'\!\big(\matr Z^{(L)}\big), \qquad \matr\Delta^{(L)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_L \times \batch}.\)(Other loss/activation pairs may yield a simpler expression; e.g. cross-entropy + sigmoid/softmax. See below.)

-

Propagate errors backward

For $\ell = L-1, L-2, \ldots, 1$: \(\matr\Delta^{(\ell)} = \Big( (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)} \Big) \ \otimes\ \sigma'\!\big(\matr Z^{(\ell)}\big), \qquad \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times \batch}.\)

Gradients for Weights and Biases (Batch)

For each layer $\ell = 1,\ldots,L$, the gradients of the cost \(J(\Theta)=\frac{1}{\batch}\sum_{n=1}^{\batch}\mathcal{L}_n(\Theta)\) are

-

Weight gradient \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} = \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top, \qquad \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell \times d_{\ell-1}}.\)

-

Bias gradient \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} = \frac{1}{\batch}\; \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} \vec 1, \qquad \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_\ell}.\)

Parameter Update (Gradient Descent)

With learning rate $\eta>0$, update for each layer $\ell=1,\ldots,L$:

\[\begin{align*} \Wmatr^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \Wmatr^{(\ell)} - \eta\,\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}, \\ \vec b^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \vec b^{(\ell)} - \eta\,\frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}. \end{align*}\]Remarks

- The backward pass must be evaluated from $\ell=L$ down to $\ell=1$ because each $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$ depends on $\matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)}$.

- The forward-pass matrices ${\matr A^{(\ell)}, \matr Z^{(\ell)}}$ are required to compute $\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}$ and the parameter gradients.

- In a standard implementation: compute all gradients first, then update all parameters.

Putting Everything Together (Full-Batch, Vectorized)

This section summarizes one full training step (full batch) in a form that maps 1:1 to an implementation.

1. Forward Pass (cache activations and pre-activations)

Initialize

\[\matr A^{(0)} := \matr X\]For each layer $ \ \ell = 1,2,\ldots,L$

\[\matr Z^{(\ell)} := \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \matr A^{(\ell-1)} + \vec b^{(\ell)} \vec 1^\top\] \[\matr A^{(\ell)} := \sigma\!\left(\matr Z^{(\ell)}\right)\]Network output

\[\matr{\hat{Y}} := \matr A^{(L)}\]What to store for backprop

\[\{\matr A^{(\ell)}\}_{\ell=0}^{L}, \qquad \{\matr Z^{(\ell)}\}_{\ell=1}^{L}.\]2. Cost (full-batch scalar)

Define the batch cost as the mean loss over the batch:

\[J(\Theta) := \frac{1}{\batch}\sum_{n=1}^{\batch}\mathcal{L}\!\left(\vec y_n^*, \hat{\vec y}_n\right).\](Equivalently: aggregate a per-example loss column-wise over $\matr Y^*$ and $\matr{\hat{Y}}$.)

3. Backward Pass

Initialize at the output layer

MSE + general activation

\[\matr\Delta^{(L)} := \big(\matr A^{(L)} - \matr Y^*\big)\ \otimes\ \sigma'\!\big(\matr Z^{(L)}\big).\]Binary cross-entropy + sigmoid output (simplified)

\[\matr\Delta^{(L)} := \matr A^{(L)} - \matr Y^*.\]For other loss functions / output actitavations other initializations apply

Propagate backward for hidden layers

For $\ell = L-1, L-2, \ldots, 1$:

\[\matr\Delta^{(\ell)} := \Big( (\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)} \Big) \ \otimes\ \sigma'\!\big(\matr Z^{(\ell)}\big).\]4. Gradients (full-batch)

For each layer $\ell = 1,\ldots,L$:

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} := \frac{1}{\batch}\;\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}\big(\matr A^{(\ell-1)}\big)^\top\] \[\frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} := \frac{1}{\batch}\;\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}\vec 1\]5. Gradient Descent Update

For each layer $\ell = 1,\ldots,L$:

\[\begin{align*} \Wmatr^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \Wmatr^{(\ell)} - \eta \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}, \\ \vec b^{(\ell)} &\leftarrow \vec b^{(\ell)} - \eta \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}. \end{align*}\]6. One Full Training Step

Forward

\[\begin{align*} \matr A^{(0)} &:= \matr X,\\ \matr Z^{(\ell)} &:= \Wmatr^{(\ell)} \matr A^{(\ell-1)} + \vec b^{(\ell)}\vec 1^\top,\\ \matr A^{(\ell)} &:= \sigma(\matr Z^{(\ell)}),\ \ \ell=1..L. \end{align*}\]Backward

\[\begin{align*} \matr\Delta^{(L)} &:= \text{(choose loss/activation-specific formula)},\\ \matr\Delta^{(\ell)} &:= ((\Wmatr^{(\ell+1)})^\top \matr\Delta^{(\ell+1)})\otimes \sigma'(\matr Z^{(\ell)}),\ \ \ell=L-1..1. \end{align*}\]Gradients + update

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}} &:= \frac{1}{\batch}\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}(\matr A^{(\ell-1)})^\top,\\ \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}} &:= \frac{1}{\batch}\matr\Delta^{(\ell)}\vec 1,\\ (\Wmatr^{(\ell)},\vec b^{(\ell)}) &\leftarrow (\Wmatr^{(\ell)},\vec b^{(\ell)}) - \eta\left(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}, \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}\right). \end{align*}\]Practical Considerations

The following topics are directly relevant when implementing and training neural networks in practice. They affect numerical stability, convergence behavior, and training efficiency.

Gradient Checking (Finite Differences)

When implementing a neural network from scratch, one of the very first validation tools you should add is gradient checking. Backpropagation formulas are easy to derive on paper but surprisingly easy to implement incorrectly (sign errors, missing transposes, wrong broadcasting, etc.). Gradient checking provides a simple but powerful sanity check that your analytical gradients are correct.

Gradient checking compares two quantities for the same parameter:

-

Analytical gradient

Computed via backpropagation: \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \theta}\), where $\theta$ is a weight or bias parameter in the network. -

Numerical gradient

Approximated using finite differences applied directly to the scalar cost function $J(\Theta)$.

If both gradients agree (up to a small tolerance), your backpropagation implementation is very likely correct.

Let $\theta$ be a single scalar parameter (e.g. one entry of $\Wmatr^{(\ell)}$ or $\vec b^{(\ell)}$). The numerical gradient is approximated by the central difference formula:

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial \theta} \;\approx\; \frac{J(\Theta + \varepsilon\,\mathbf e_\theta) - J(\Theta - \varepsilon\,\mathbf e_\theta)} {2\varepsilon},\]where:

- $\varepsilon > 0$ is a small step size (e.g. $10^{-5}$),

- $\mathbf e_\theta$ denotes a perturbation that affects only parameter $\theta$,

- $J(\Theta)$ is the total cost of the network, i.e. \(J(\Theta) = \frac{1}{\batch}\sum_{n=1}^{\batch}\mathcal{L}\!\left(\vec y_n^*, \hat{\vec y}_n\right).\)

Importantly, no backpropagation is used to compute this quantity; only forward passes.

For a given layer $\ell$, gradient checking compares:

-

Backprop gradient \(g_{\text{bp}}\)

\[\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}, \qquad \frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}\] -

Numerical gradient \(g_{\text{num}}\)

The comparison is can be done using a relative error score:

\[\mathrm{rel\_err} = \frac{\lvert g_{\text{num}} - g_{\text{bp}} \rvert} {\lvert g_{\text{num}} \rvert + \lvert g_{\text{bp}} \rvert + \varepsilon_{\text{stab}}},\]evaluated element-wise, where $\varepsilon_{\text{stab}}$ is a small value like $10^{-12}$ which is added to the denominator for stability reasons. A common rule of thumb for interpretation for \(\mathrm{rel\_err}\):

| Relative error | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| $< 10^{-7}$ | Excellent (almost certainly correct) |

| $10^{-7}$ – $10^{-5}$ | Probably fine |

| $10^{-5}$ – $10^{-3}$ | Suspicious |

| $> 10^{-3}$ | Very likely a bug |

Small absolute gradients are usually exempted from strict relative-error checks.

Practical Remarks

- Gradient checking is slow: each parameter requires two forward passes. → Use it only for debugging, never during real training.

- Check one layer at a time, not the whole network at once.

- Disable regularization, dropout, and data shuffling while checking.

- Once gradient checking passes, turn it off permanently and trust backprop.

In our example implementation, gradient checking is performed by perturbing individual entries of $\Wmatr^{(\ell)}$ or $\vec b^{(\ell)}$, recomputing the total network cost $J(\Theta)$, and comparing the resulting numerical gradients against the gradients produced by backpropagation. This clean separation (numerical gradients from forward passes only, analytical gradients from backprop) makes gradient checking a reliable correctness test.

Batching Strategies

In practice, the cost function

\[J(\Theta) = \frac{1}{\batch}\sum_{n=1}^{\batch}\mathcal{L}_n(\Theta)\]is rarely evaluated over the entire training set at once. Instead, training data is processed in batches, leading to different optimization regimes.

-

Full-batch gradient descent

The gradient of $J(\Theta)$ is computed using all available training examples. This yields an exact descent direction but is computationally expensive and impractical for large datasets. -

Mini-batch gradient descent

The dataset is split into smaller batches of size $\batch \ll N_{\text{data}}$. Each update uses \(J_{\text{batch}}(\Theta) = \frac{1}{\batch}\sum_{n=1}^{\batch}\mathcal{L}_n(\Theta),\) providing a good trade-off between computational efficiency and gradient quality. This is the standard choice in modern deep learning. -

Stochastic gradient descent (SGD)

A special case of mini-batch training with $\batch = 1$. Updates are noisy but inexpensive and can help escape shallow local minima and saddle points.

All three methods share the same backpropagation equations; only the batch size $\batch$ differs. In our example below, we use the full-batch approach.

Weight Initialization

Weight initialization plays a critical role in training neural networks. In particular, initializing all weights to zero is a bad idea, because it breaks learning entirely: if all weights in a layer start with the same value, then all neurons in that layer compute identical activations and receive identical gradients during backpropagation. As a result, they remain indistinguishable throughout training, and the network effectively behaves as if each layer had only a single neuron. Random initialization is therefore essential to break this symmetry between neurons.

In our implementation, we use Glorot (Xavier) uniform initialization for the weights. For a layer with $d_{\ell-1}$ input units and $d_\ell$ output units, the weights are drawn from a uniform distribution

\[w_{i,j}^{(\ell)} \sim \mathcal{U}\!\left( -\sqrt{\frac{6}{d_{\ell-1}+d_\ell}}, \ \sqrt{\frac{6}{d_{\ell-1}+d_\ell}} \right).\]This choice is motivated by the desire to keep the variance of activations and gradients approximately constant across layers, which helps to avoid vanishing or exploding signals during the forward and backward passes.

Bias terms are initialized to zero,

\[\vec b^{(\ell)} = \vec 0,\]which is common practice and does not cause symmetry issues, since symmetry is already broken by the random weight initialization.

Further reading.

Other widely used initialization schemes include He initialization (for ReLU-based networks), orthogonal initialization, and data-dependent or adaptive initialization strategies. These approaches are discussed extensively in the literature.

Learning Rate (Step Size)

The learning rate $\eta>0$ controls the size of the parameter update in each gradient descent step,

\[\Wmatr^{(\ell)} \leftarrow \Wmatr^{(\ell)} - \eta\,\frac{\partial J}{\partial \Wmatr^{(\ell)}}, \qquad \vec b^{(\ell)} \leftarrow \vec b^{(\ell)} - \eta\,\frac{\partial J}{\partial \vec b^{(\ell)}}.\]Choosing an appropriate step size is crucial:

- If $\eta$ is too small, training progresses very slowly and may appear to stall.

- If $\eta$ is too large, the updates can overshoot minima, leading to oscillations or divergence of the cost function.

In practice, $\eta$ is often treated as a hyperparameter that must be tuned experimentally. More advanced methods adapt the effective step size automatically during training; these are discussed in the further reading section.

Input Normalization

Neural networks are sensitive to the scale and distribution of input features. If different input dimensions have very different magnitudes, the optimization problem becomes poorly conditioned, which can significantly slow down training.

A common remedy is input normalization, applied to the input matrix $\matr X = \matr A^{(0)}$ before training:

-

Feature scaling

Rescale each input feature to a comparable range (e.g. $[0,1]$), preventing some features from dominating others. -

Zero-mean / unit-variance normalization

Standardize each feature by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation, \(x_{i,n} \leftarrow \frac{x_{i,n} - \mu_i}{\sigma_i},\) where $\mu_i$ and $\sigma_i$ are computed over the training set.

Well-normalized inputs lead to more stable gradients and typically result in faster and more reliable convergence.

Vanishing and Exploding Gradients

In deep networks, gradients are propagated backward through many layers via repeated matrix multiplications and element-wise derivatives. If these factors are consistently smaller than one, gradients can vanish; if they are larger than one, gradients can explode. Both effects impair learning: vanishing gradients slow or stop updates in early layers, while exploding gradients lead to numerical instability.

Common causes include poor weight initialization, unsuitable activation functions (e.g. sigmoid in very deep networks), and deep architectures without normalization.

Practical mitigation strategies:

- Careful weight initialization (e.g. Glorot initialization)

- Appropriate activation functions (sigmoid, as used in our example code might be a bad choice for deep nets)

- Input normalization and regularization

- Gradient clipping (to control exploding gradients)

Convergence Issues

Even with correct gradients, optimization may behave poorly:

-

Divergence

Often caused by an excessively large learning rate, leading to overshooting and unstable updates. -

Slow convergence

Can result from poor conditioning of the optimization problem, unnormalized inputs, or an overly small learning rate. -

Plateaus and saddle points

Regions where gradients are close to zero but are not local minima, causing training to progress very slowly.

Understanding and diagnosing these behaviors is essential for successfully training neural networks in practice.

Training, Validation, and Test Data

In practical machine learning workflows, the available data is typically split into three disjoint subsets:

-

Training set

Used to compute gradients and update the parameters $\Theta$ via backpropagation and gradient descent. -

Validation set

Used to monitor performance during training (e.g. for hyperparameter tuning, early stopping, or model selection) without influencing the learned parameters directly. -

Test set

Used only once, after all training decisions are finalized, to obtain an unbiased estimate of the model’s generalization performance.

This separation is crucial because evaluating a model on the same data used for training leads to optimistically biased performance estimates and can mask overfitting.

In the example below, we deliberately train on the full dataset to keep the mathematical derivations and implementation as transparent as possible. Since the goal here is to understand how backpropagation works (not to assess generalization performance) this simplification is intentional. For any real-world application, however, proper train/validation/test splits are essential.

Further Reading

The following topics extend (however, the list is still fairly incomplete) beyond the basic feed-forward network and are useful for deeper understanding or more advanced applications.

- Regularization

- L2 (weight decay)

- L1 regularization

- Early stopping

- Adaptive optimization methods

- Momentum

- RMSProp

- Adam, AdamW

- Advanced activation functions

- ReLU, Leaky ReLU, ELU

- GELU, Swish

- Softmax (multiclass classification)

- Loss functions

- Binary cross-entropy

- Categorical cross-entropy

- Mean squared error (MSE)

- Mean absolute error (MAE)

- Huber loss

- Numerical stability tricks

- Log-sum-exp trick

- Stable softmax implementations

- Bias–variance tradeoff

- Overfitting vs. underfitting

- Initialization and symmetry breaking

- Second-order methods

- Newton’s method

- Quasi-Newton methods (L-BFGS)

- Backpropagation efficiency

- Computational graphs

- Automatic differentiation

- Other neural network architectures

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

- Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

- Transformers

- Other training techniques

- Batch normalization

- Layer normalization

- Dropout

- Expressivity and depth

- Shallow vs. deep networks

- Universal approximation theorem

These topics build on the foundations presented in this post and are good entry points for further study.

Accompanying Jupyter Notebook (Code Companion)

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: